Blog by James Aaron Green

In a recent Times article, the columnist Matthew Parris argues that it is time to lift the taboo on assisted dying in cases of “extreme senescence.”1 This call for what amounts to voluntary euthanasia—for each person to recognise ‘“Your time is up”’—was “widely condemned” for its reductive, dehumanizing verdict upon the worth of old age.2 For myself though, as a literary historian, Parris’s most intriguing suggestion is that, unconsciously, “our culture is changing its mind” on the value of old age attended by infirmity. A clear-eyed look at history reveals the opposite: conceiving of old age in economic terms perpetuates rather than departs from ideas originating in the UK and US at the end of the nineteenth century, ideas which can be traced through the twentieth century up to today.

Beginning in the 1870s, the UK saw agitation for a national pension scheme to provide for the growing number of older persons. The country was the first to enter the demographic transition that is almost ubiquitous today: from high mortality and high fertility to low mortality and low fertility. Declining infant deaths had radically shifted life expectancy, but the increasing visibility of those in their later years meant that Britain was seized by a sense of “growing old” as the century drew to its close.3 The social researcher Charles Booth would later provide evidence of the scale of old-age poverty, but even before he documented this issue Britain’s aged cohort was feared to be an economic burden whose needs were a looming threat to social cohesion. Could and should future generations pay for its members, and would this risk their own opportunities?

The US, too, felt these anxieties. In American Nervousness (1881), the neurologist George Miller Beard sought to quantify the relationship between age and productivity for the first time. He painted a bleak picture of later-life value by supposedly proving that the majority of work was done by people under forty. As Thomas Cole summarizes his viewpoint, “since [Beard] celebrated the ‘race for life’ rather than seeking to alter or mitigate its effects, [… he] considered old age economically worthless, full of disease, and burdensome.”4 Whereas the Puritanical tradition had regarded old age as having a unique perspective and existential purpose, Beard deemed it an inferior counterpart to the normative ideal of vigorous youth.

Then the writer Anthony Trollope addressed this topic with his dystopian satire The Fixed Period (1882). The novel is set in a fictive former British colony that has mandated euthanasia for those aged 67.5 and over. Life beyond the expected years of productive labour is deemed more than worthless—it is a burden to society. “How are a people to thrive when so weighted? And for what good?” the narrator asks.v Before the killings take place, however, the unpopular government and its flagship policy are virtuously overthrown. The satire exposes what Trollope saw as the growing spiritual poverty of his times when it came to old age, especially its narrow focus on chronological age as a barometer of usefulness. A fulfilling and meaningful old age becomes incompatible with physical decline when a culture reduces the value of life to a matter of productive capacity.

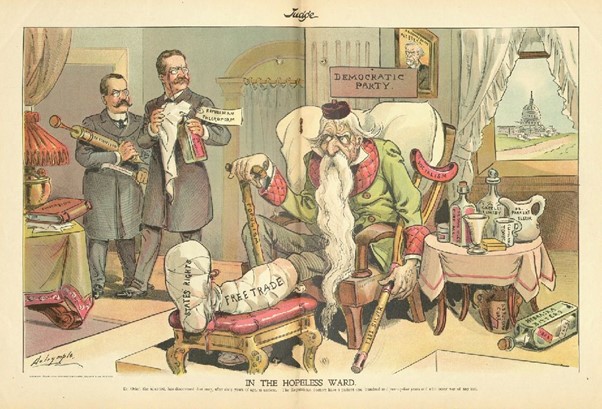

The Fixed Period became a touchstone for the idea of a burdensome old age. In 1905, when the physician William Osler made his farewell speech to the Johns Hopkins Medical School, he jokingly affirmed Trollope’s fictional proposal. Real work, he said, was done by those under forty, whilst only “calamities” awaited men in their seventies and eighties.6 Despite their mild intention, Osler’s remarks provoked a backlash. Publications from the New York Times to the Washington Post refuted them with stories of successful older men, while elsewhere they were used to lampoon US politics (Fig. 1). The scale of the response far exceeded the novelty of the suggestion, reflecting, perhaps, a recognition that old age had indeed become devalued with economic, social, and political systems geared toward maximising productive output. Twenty years after Trollope’s The Fixed Period, proposing age-based euthanasia had become, at least for some, an ill-fitting subject for satire.

By the end of the twentieth century, though, such views were no barrier to success. Sherman B. Nuland’s bestselling How We Die (1995) considers, like Parris, the affordability of old-age infirmity and illness. His conclusion is likewise framed by economics, though purporting to prioritize humanitarian concerns; continuing to provide care for such persons would “break the hearts of those we love and of ourselves as well, not to mention the purse of society that should be spent for the care of others who have not yet lived their allotted time.”7 For Nuland, illness and infirmity may not be bounded by chronological age, as in Beard’s study or Trollope’s satire, but he takes them as a sign that the older person has lost their claim upon societal resources and should reject efforts to keep themselves alive for longer.

Reversing Nuland’s argument, Felicia Ackerman asks, “doesn’t it demonstrate vanity and selfishness on the part of the young to rank their ‘careers and resources’ above old people’s very lives?”8 This provocation may remind us of the COVID-19 pandemic when we saw calls for older people to sacrifice themselves to benefit the consumerist economy—thinly veiled as an act of generational assistance (in fact, young people broadly accepted the restrictions).9 These mirrored moments, reflecting also those from the 1880s and 1900s, show that Parris’s claims for the unsustainability of “extreme senescence” hardly represent a culture “changing its mind.” To do so, in fact, would require the reverse: to rethink old age and aging outside of productive (in)capability. The question becomes can we recover for our aging an existential purpose that has been progressively displaced over the past century and a half?

James Aaron Green is a postdoctoral researcher (ÖAW APART-GSK) at the Department of English and American Studies, University of Vienna. He is a literary historian of age and aging in the mid-to-late C19th and early-C20th centuries.

References

[1] Matthew Parris, “We Can’t Afford a Taboo on Assisted Dying,” The Times, March 29, 2024, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/we-cant-afford-a-taboo-on-assisted-dying-n6p8bfg9k.

[2] Sonia Sodha, “When the Right to Die Becomes the Duty to Die, Who Will Step in to Save Those Most at Risk?” The Guardian, April 7, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/apr/07/conflicted-legalising-assisted-dying-sonia-sodha.

[3] Teresa Mangum, “Growing Old: Age,” in A New Companion to Victorian Literature and Culture, ed. Herbert F. Tucker (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

[4] Thomas R. Cole, The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging in America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 168.

[5] Anthony Trollope, The Fixed Period, (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1882), 1:6.

[6] Cole, Journey of Life, 171.

[7] Quoted in Felicia Ackerman, “No Exit,” The American Scholar 64, no. 1 (Winter 1995): 132.

[8] Ackerman, “No Exit,” 132.

[9] “Coronavirus and Compliance with Government Guidance, UK: April 2021,” Office for National Statistics, release date April 12, 2021, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronavirusandcompliancewithgovernmentguidanceuk/april2021#young-people-compliance.