Podcast by Clare Barker and Lynn Wray

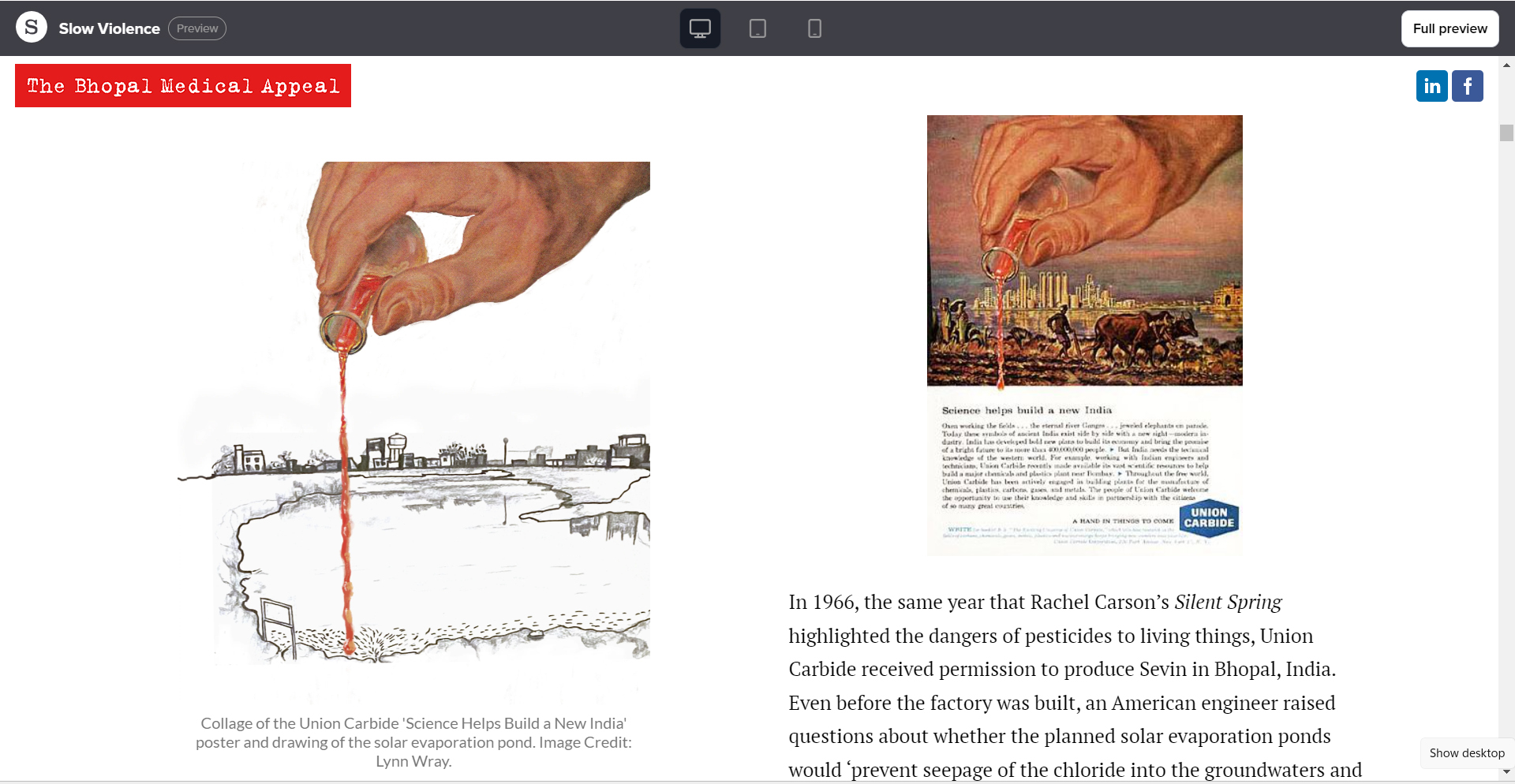

The 1984 Union Carbide gas disaster in Bhopal, India, is recognised as the world’s worst industrial disaster. It has killed around 25,000 people to date, and the health of thousands of families in Bhopal continues to be affected by a groundwater supply contaminated by toxic chemicals from the now abandoned Union Carbide factory site. The Wellcome-funded LivingBodiesObjects project has been working with the Bhopal Medical Appeal, a charity funding free healthcare for disaster survivors and water-affected communities. In this podcast episode, LBO team members Clare Barker and Lynn Wray and the BMA’s Jared Stoughton introduce their collaborative work to produce new digital resources emerging from the stories of survivors and activists in water-affected areas of Bhopal. They discuss the challenges of telling complex stories in digital media formats: how to keep readers’ attention? How to resist the simplifications of clicktivism? How to maintain public interest in a disaster that happened 40 years ago? Their work-in-progress aims to make visible the ‘slow violence’ of the toxic water supply, as described in survivors’ stories, via original artworks and animations focusing on water infrastructure (ponds, pipes, taps, tanks) and everyday objects such as buckets and utensils, and experiments with ways of engaging readers’ attention and care.

Jared Stoughton is Campaigns Officer for the Bhopal Medical Appeal.

Lynn Wray is a practice researcher and the Research Fellow on the LivingBodiesObjects project at the University of Leeds.

Clare Barker is Associate Professor in English at the University of Leeds and one of the five Co-PIs on the LivingBodiesObjects project.

To learn more about the Union Carbide disasters and the work of the Bhopal Medical Appeal, please visit www.bhopal.org. You can also find them on Facebook and Instagram.

TRANSCRIPT

SCHILLACE: Hello and welcome back to the Medical Humanities Podcast. I’m Brandy Schillace, the Editor in Chief and your host today. So we’ve come back again to talk to members of the LivingBodiesObject Project, and we’re going to talk about the Bhopal disaster today with Clare Barker, Lynn Wray, and Jared Stoughton, who’ve joined me. Hello and welcome.

BARKER: Hello. Thanks for having us.

STOUGHTON: Nice to meet you.

SCHILLACE: It’s good to have you. I think it would be wonderful if each of you could give just a brief mention of who you are and what you do, and then give us a little context, too. Because, of course, for many of our listeners, this was a disaster that happened a number of years ago now, and some of them might not have it quite on their frontal lobe. So, let’s introduce each of you. Clare, tell me a bit about yourself and then Lynn and then Jared.

BARKER: Sure. So I’m Clare Barker. I’m an Associate Professor in the School of English at the University of Leeds, and I work on representations of health and disability in contemporary global literatures. And I’m one of the five co-principal investigators on the LivingBodiesObjects Project, and I’ve been working closely with the Bhopal Medical Appeal, who one of our project partners.

SCHILLACE: That’s wonderful. And of course LivingBodiesObjects, we’ve had Stuart. We’ve had a number of people on, and this is kind of a continuation. I wanna say this is maybe our fifth one? I’d have to go back and check. But if you’re tuning in for the first time, you can find those. They always have LivingBodiesObjects in the title. And you can go back and listen to other podcasts that we’ve done. Lynn?

WRAY: Hiya, I’m Lynn Wray. I’m a practice-based researcher at the School of Media and Communication at University of Leeds. At the moment, I’m research fellow for the LivingBodiesObjects Project, working alongside Clare and several other researchers, and I’ve worked across all of the residencies. My background’s working in museums and galleries and as a creative practitioner. And at the moment, I’m really interested in how to tell complicated stories with different facets, such as the Bhopal gas disaster, that have a kind of intersection between health and technology, and how we can do this through visual media in different ways.

SCHILLACE: That’s great. And Jared?

STOUGHTON: Hi. My name’s Jared Stoughton. I am the Campaigns Officer for the Bhopal Medical Appeal, and we’re a charity who basically provides free healthcare to survivors of the 1984 Bhopal Union Carbide gas disaster.

SCHILLACE: That’s wonderful. And I know, like I said, I feel like this context, it’s something people have heard about, but I don’t know if people, especially young people, have a real concept of exactly what happened in the Bhopal disaster. So I wonder if you could give us a little bit of context about that and how you’re working with survivors.

STOUGHTON: Yes. Of course. So, essentially, an American corporation called Union Carbide built a chemical factory, a pesticide factory, in the Indian city of Bhopal in 1969. And it operated for some years, and due to issues with the operation and costs, they were thinking about closing it in the early ‘80s. And in 1984, on December 2nd during routine maintenance—supposedly routine—water entered one of the tanks containing Sevin, which is a pesticide. There was a chemical reaction, and it ended up leaking 27 tons of the deadly gas known as methyl isocyanate, which basically blew across the city of Bhopal. And it affected half a million people in the course of a single night.

SCHILLACE: Mm.

STOUGHTON: Thousands of those had died by morning, and many more were left with life-changing injuries and illnesses.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

STOUGHTON: The kind of true extent of the damage that was done is still contested. Official figures say the death toll was somewhere around 1,500 to 2,000 in the first three days. Survivor accounts and studies done since, including by Amnesty International, suggest it was much, much higher, probably something more in the region of 7 to 10,000 people who died in those first 72 hours.

SCHILLACE: Okay.

STOUGHTON: And we believe since then, about 25,000 people have died as a result of the disaster. It does remain to this day the world’s biggest industrial disaster.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

STOUGHTON: And essentially what we do is we work with the survivor communities to provide free healthcare to those with long-term injuries and illnesses, as well as children who are still being born into gas-affected families who have a number of different disabilities and injuries as a result of that exposure.

SCHILLACE: Okay. That’s, I’m assuming some of that would be congenital as well, would it not?

STOUGHTON: It is, yeah.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

STOUGHTON: So, currently, it’s the third generation of children who are being born with congenital disabilities.

SCHILLACE: Okay.

STOUGHTON: There are two reasons for that. One is the exposure to the gas, which was suffered by their immediate families, they’re now parents, and in some cases, grandparents. But also, ongoing water contamination as a result of [unclear; cross-talk].

SCHILLACE: Right. Environmental.

STOUGHTON: Yeah. So the factory site was never properly cleaned. All the pesticides that were left at the site ended up sinking into the groundwater there, affecting people’s wells and water pumps. And some of those children’s parents have been drinking that water, sometimes while pregnant. Sometimes the kids themselves have been exposed to it, and that’s also causing a major second health disaster, which is ongoing.

SCHILLACE: Okay, right. No, that makes sense. It makes me think. I think a lot of our listeners are familiar with Chernobyl and the kind of after effects of that, but much, many fewer people are familiar with the Bhopal disaster, which I think we can make some assumptions about why that might be.

So, perhaps we could talk then about how the LivingBodiesObjects Project has been partnering with the Bhopal Medical Appeal and how you’re sort of working together and what you’re doing as a, in the context of the survivors.

BARKER: Yeah. So, the LivingBodiesObjects Project, if you haven’t listened to any of the other podcast episodes yet, we’re working with various organizations that have, that work with health communities and disabled communities in different ways and thinking about experimenting with creative ways to tell stories about health. And yeah, we wanted to work with the Bhopal Medical Appeal because they’re a really interesting charity in the way that they tell the story of the Bhopal disaster. I think there’s a lot of charities that focus on images, say, of disabled children and create narratives around suffering and pity, and in doing so, kind of reinforce certain power relations between survivors of disasters and the donors who might support their causes. And what the Bhopal Medical Appeal does that’s really interesting, I think, is kind of shifts that relationship. They tell stories about people’s health and about disability, and they include images of people affected by the disasters.

But the BMA have traditionally used like long-form storytelling in their adverts, often in broadsheet newspapers and things like that, that actually require the viewer to do a lot more work, I think, in terms of engaging with the story that’s told. So it’s not a kind of a clicktivism model of kind of just see an image and have an emotional reaction and donate. It’s you are told a story. You’re asked to engage with something kind of ethically and politically. And yeah, and it feels like there’s much more of an exchange going on, as in the reader is being informed and given a story and informed, rather than just a kind of a one-way relationship. So, that’s kind of why we wanted to work with the BMA, ‘cause we thought they were doing something really interesting in terms of their stories and representations.

What we’ve been doing with them is experimenting with some digital storytelling methods and thinking about how we might, how they might, as an organization, adapt some of those long-form storytelling techniques for digital media. And thinking about some of the challenges of that to do with the kind of attention economy and kind of 24-hour news cycles and the speed of things. So, yeah, so we’ve been experimenting with some digital storytelling too.

SCHILLACE: And artwork too, am I wrong? Am I right about that, artwork as well? And who creates, is the artwork and stories, the stories are the survivor stories. Is the artwork also from the survivors, or is it created around the situation to generate interest?

STOUGHTON: Yeah, Lynn, would you like to speak on this one?

WRAY: [laughs] Yeah, I can come in with the sort of two different sets of artwork that’s been produced as part of our work with the BMA. One of which Jerad might tell you a little bit more about following me speaking, produced by Charlotte, who has been working directly with the BMA to develop some work around the Sambhavna Clinic. And I’ve been, we basically had conversations with survivor groups about kind of everyday evidence they experience of water contamination as really part of the original conversations we had about how we could think about telling the story of water contamination. And we were told that everyday utensils and infrastructure often showed signs of the contamination which they saw gradually unfolding over years, and maybe someone who didn’t own that object or interact with that infrastructure every day might not notice. And one of the other kind of research questions we had for LivingBodiesObjects, well, between us and the BMA, was about how we could slow down someone engaging with the stories and try and ask for a slower kind of attention.

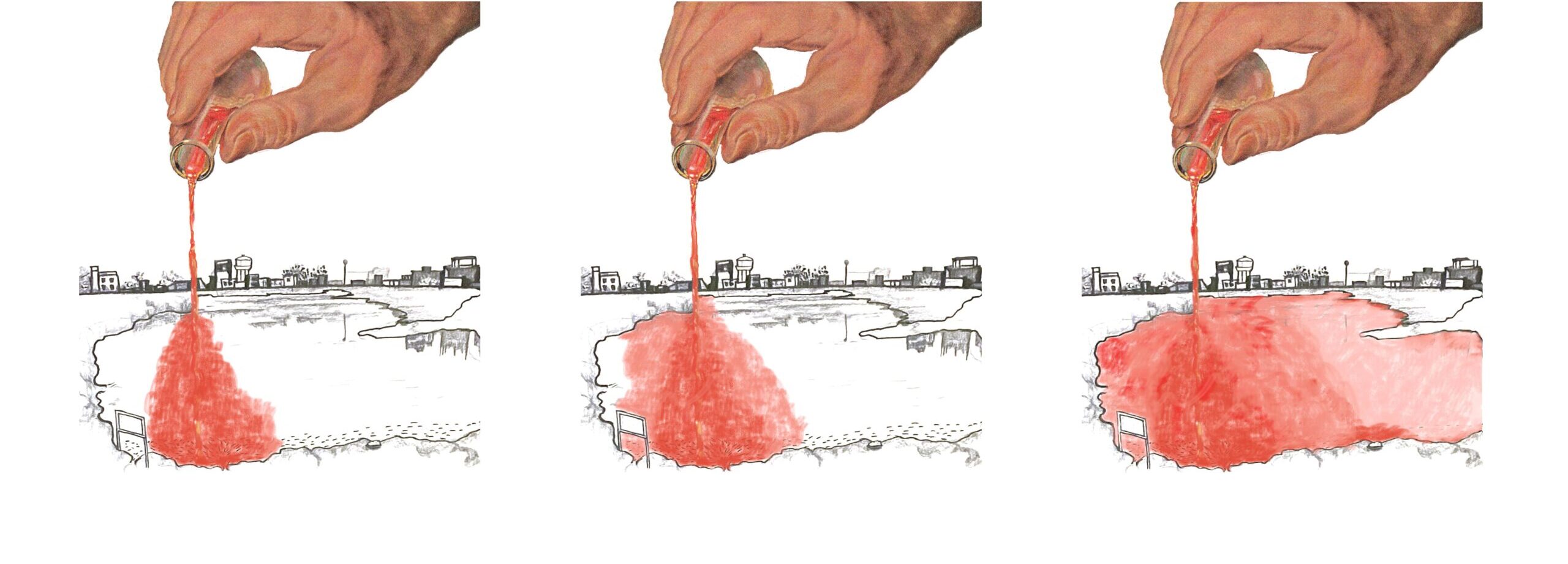

So, we’ve been using this platform called Shorthand, which is a kind, uses techniques like scrollimation, which is like animations that kind of emerge as you read the text alongside it.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, mmhmm.

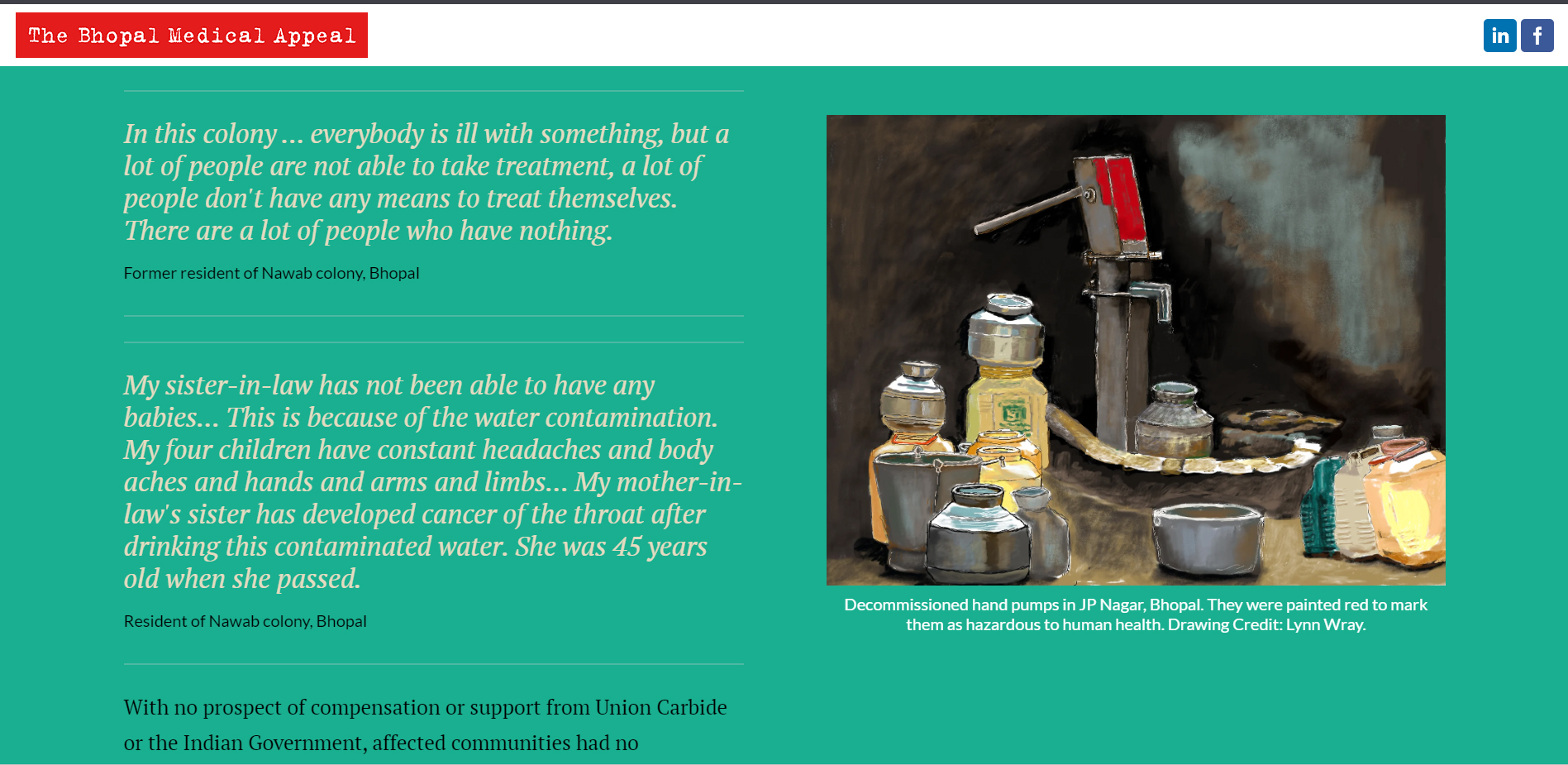

WRAY: So I’ve been creating some drawings of objects that we’ve, specific objects and infrastructure, that we’ve been shown, like decommissioned hand pumps, buckets, and bowls that are showing the kind of wearing and rusting and evidence and discoloration and things that have happened, scaling, peeling away of metal, things like that that’ve happened to the objects that survivors have told us and shown us as being evidence of the water contamination. So, I’ve been drawing these and turning them into animations that are paced quite slow that only work if you view them alongside the text and you read the text that’s the kind of survivor story at the same time. So that’s been one of the ways we’ve been trying to engage with the survivors’ stories.

WRAY: So I’ve been creating some drawings of objects that we’ve, specific objects and infrastructure, that we’ve been shown, like decommissioned hand pumps, buckets, and bowls that are showing the kind of wearing and rusting and evidence and discoloration and things that have happened, scaling, peeling away of metal, things like that that’ve happened to the objects that survivors have told us and shown us as being evidence of the water contamination. So, I’ve been drawing these and turning them into animations that are paced quite slow that only work if you view them alongside the text and you read the text that’s the kind of survivor story at the same time. So that’s been one of the ways we’ve been trying to engage with the survivors’ stories.

SCHILLACE: I think that’s really interesting. I wanna draw attention to this just for a moment for our listeners, because I think lots of times when we think about artwork in the context of social justice and medical humanities, we’re usually asking, oh, it’s therapeutic, and we’re asking the sufferers, the survivors, the patients to produce that as part of therapy. And this is a very different kind of thing. And I really appreciate that because I feel as though artwork, often, art as a part of medical humanities, frequently gets turned into therapy as opposed to—which is powerful in its own right—but as opposed to acting upon the reader. As opposed to acting upon somebody and asking them to engage. And that’s a very different way of utilizing art in medical humanities that we don’t often see.

And I think also, I have seen this kind of storytelling done. I saw some of it during the #MeToo movement, for instance, where people were trying to keep you from looking away, right? Because sometimes those stories are hard to read. And they were using these kind of it’s not exactly pop-up exactly, but [laughs] it was not pop-up video, right? But it is something like that where it’s like you’re getting something, and it works with our reward system, our psychological reward system. You know you’re going to get something for continuing on. So, that is fascinating to me that this is something coming as a key part of the production of information, but you’re still getting the objects and the ideas about what’s happening to those objects from the sufferers. And I’m here in the United States. I would love to see something like this on Flint, Michigan, for instance, because it seems like a really similar kind of situation, would benefit in the same way.

Jared, did you, I think Lynn said you could add something a little bit more specific about how you guys are engaging.

STOUGHTON: Yeah. So I’ve got a couple of things here together, really. So, Clare’s right, that in our history, the charity’s been very much founded on long-form storytelling. And in fact, we were founded off the back of a single ad run in The Guardian newspaper back in 1994. That’s where the initial revenue came from. And that money was used to open a clinic for survivors, essentially run by survivors as well. And that was the Sambhavna Clinic. And what they discovered basically was that the damage done to a lot of the survivors due to the gas was so extensive that many of them basically couldn’t benefit from modern drugs.

SCHILLACE: Mm.

STOUGHTON: Things like painkillers were difficult for their bodies to absorb ‘cause they had liver damage or kidney damage. And most, if not all, have lung damage as well. As a result of that, they actually experimented with using traditional Ayurvedic techniques and herbal medicines basically to help relieve symptoms without damaging people’s organs further. And they combine that with modern medicinal techniques. It was actually incredibly successful.

SCHILLACE: Oh, yes, yes.

STOUGHTON: We tried to incorporate some of that into the story. And Charlotte, who Lynn mentioned, is actually a medical illustrator, and she’s done some beautiful images of, to kind of represent some of this healing, actually, with flowers growing out of people’s organs. But there’s this sense of trying to, after the kind of damage that was done to the environment as well as the people, that the clinic’s kind of built on a sustainable model and is largely about trying to bring back some of that life and community feeling and have a really positive space of healing after kind of the horror of the disaster.

And we really want that to be an important part of the story, really, that there is this healing. That the survivor community is this amazing kind of resilient group of people who have been involved in activism for years as well. They’ve always campaigned for justice, and that’s very much a part of the story. And even the individual stories we share of those survivors, we really want to kind of emphasize these positive elements that these people are not just victims. They really are in charge of their own destiny. So, we’re kind of hoping that this kind of, it’s a difficult thing to tackle moving into a digital space, because it’s gonna be 40 years this December since the disaster originally happened, and it’s so much ground to try and cover. But we’re hoping this mix of media and this kind of long-form digital way of approaching it will actually really help us to keep people engaged and to learn about Bhopal afresh as kind of an ongoing issue and not just a piece of history.

SCHILLACE: Well, and I think that’s incredibly important too, because we tend to treat with, oh, 40 years ago, we tend to treat that as though [scoffs], you know, somehow that’s over. I think we’re gonna see this again with COVID. There’s no over. People continue to suffer consequences long after the fact. And so, I can see people going, “Why are we still talking about this?” And it’s like, because it’s still happening, you know? It doesn’t go, these things don’t go away, and particularly when you consider about contamination and the kind of half-life of these things.

BARKER: That’s one of the things we were wanting to address, really, in our work. You know, there’s that idea of how do you get people to care about a disaster that happened 40 years ago? It’s a really pressing question, especially as people age and young people now don’t, haven’t heard of the Bhopal disaster. And so, one of the ways we were thinking about that is if we tell this whole complex story that’s about the gas disaster and then the ongoing water contamination, but we wanted to put quite an emphasis on the water contamination, a lesser-known part of the story. I think a lot of people who’ve heard of the Bhopal disaster don’t realize that the water contamination is ongoing. Because it connects with a lot of concerns globally about pollution and forever chemicals and contaminated water supplies in different places in the world. You mentioned Flint, Michigan, and there’s lots of examples of communities that are affected by contamination in this kind of way.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

BARKER: And so, we wanted to place an emphasis on that. And just kind of going back to something that Lynn said about the images that we’re using, there’s so much powerful photography telling the story of Bhopal going back 40 years and photographers who’ve been back in communities more recently. And we use some of that photography in our digital storytelling, but we also wanted to emphasize, like Jared’s been saying, the activism and the community, the amazing community structures that’ve kind of built up in Bhopal to support survivors. And so, by experimenting with objects and water infrastructure and buckets and pots and pans and things like that, we wanted to emphasize the communal aspects of things and wanted to ask and wanted to emphasize kind of the structural issues of the problem as well. So, not just like this is the story of one person and their health and, you know, donate. And it’s kind of more thinking about the kind of structural issues at stake, the possible solutions that could come through changes in the water supply and things like that. So, yeah, we were trying to do a number of things, I think, with the storytelling. But yeah, emphasizing the community support and activist groups that are there and thinking about the structural nature of the problems was one of our many focus points.

SCHILLACE: And Clare and Lynn, you’re both with LivingBodiesObjects. And again, for those who aren’t familiar, there’s no space. So LivingBodiesObjects is something that we’re talking about. LivingBodiesObjects is one word. And I think that that’s important to address because you’re, this is the perfect case study of how objects and living bodies are not separate. They interact, and they stand in for one another and represent one another. And so, again, to return to Lynn’s work on the imagery and how that’s being made part of the story, objects are parts of our lives in a way that people tend to ignore frequently in medicine. And I think in some ways, I think it’s a Western problem. Actually, this whole thing is a Western problem when you consider where the company came from. But the fact that, like, there’s a lot that Ayurvedic medicine has to offer, and I think we forget that. It’s not just a cultural practice. We too often in the West are willing to go like, “Oh, we have the answers, and we’ll let these other folks take part,” without realizing they have answers. Cultural, these different kinds of medical practices in different cultures—I used to work for a cultural anthropology journal—have impact and things to tell us. So, in a great way, I mean, so I can see why these two projects work so well together, because I feel like you’re crossing boundaries. You’re showing that the boundaries are, in fact, perhaps permeable or even imaginary. And I think that’s incredibly powerful.

BARKER: You know, the kind of theoretical underpinnings of what we’re doing, one of the things we’re thinking about was Rob Nixon’s idea of slow violence and the idea of how do you make visible violence or damage that is happening under the ground, in the water supply, in the cells of the human body? And so, the objects is one really brilliant way to make that visible. And we’re thinking very much about the kind of entanglement or the transcorporeality between bodies and objects and people’s bodies in the community, the environments in which they live, the objects that they use. So, yeah, that’s something we wanted to bring out in the project, definitely.

SCHILLACE: And I think LivingBodiesObjects as a whole concept is really interesting, but I feel that perhaps for our listeners, this might be the first time where it seems very concrete, this connection. I want to get back to the challenges of the digital storytelling. So, am I right to think, Lynn, you’re the one building the actual digital space, or is that something all three of you are working on?

WRAY: We all worked on it as a sort of whole team, really. And then when it came to putting it together, I’ve been experimenting a bit more with how, probably had more of the hands-on input into Shorthand, but we discussed it as a whole or even with members of the project team. Almost everyone in the BMA has been involved in one way or another. So, people have been working on the textual elements, thinking about quotes from survivors that might be inputted. And then we’ve been thinking about the order, and yeah, thinking about how to combine different types of the visual elements as well. And at the moment we’re not, we’re still in progress. We’re not finished with it yet. And we’re sort of having a bit of a, we’re at a kind of junction with that where we’re having a bit of a rethink about the structure and how it might best work, which has been a really interesting process, actually working through it as a team. And I think we’ve kind of got to the same place now as to how we think it might best work.

SCHILLACE: I’m interested myself because I also work, I actually used to be a website designer because I’ve had every job that there is and have lived 400 years. No, but [laughs] freelance people, we’re like that, right? I’m a gig economy. But I used to build websites, and I have my own website. I’m an author and a freelance journalist as well as an editor. And having a website is a peculiar thing now, too, because people don’t access websites like they used to. You didn’t, once upon a time, that was like a warehousing for everything. And you went there, and you went from page to page to page, and that’s no longer the case. In fact, I have a meeting with my web design team, the people who designed for me, in the coming months to say, okay, people access digital content so differently. They want it to look modular. It almost has to be you can see it on a page, or you can see it on one screen of your phone, or it has to have these pieces that you can absorb quickly and move on and, you know, swipe, swipe, right?! And I don’t quite know how to engage with that, and I feel like that has become something that’s quite difficult to do in this sort of TikTok world of two minutes-or-less videos. How do we encourage people to continue?

And I’ve become the same way. I find, when something is too long, I’m like, oh, I’m not reading that. Well, wait a minute. [chuckles] I read whole books. What am I thinking? But it’s true. So, as you’re, I’m very interested to know what, structurally, you have decided upon and what kind of decisions you’ve made. Because I feel like all of us who create content digitally are in a place of having to refit content to a new structure, and the structure hasn’t solidified. So, by all means, do tell us. I think that’s something that’s fascinating.

WRAY: I think we are now thinking about it more like a kind of magazines style format, just ‘cause there’s so much. We originally wanted it to be a bit more like a long read, long form. And I think there will be a part of it, like a section that is still long form, and you can read it through as a kind of whole flow. But because of the complexity and interweaving between the gas disaster and water contamination, wanting to give space to survivor stories as well, we’re now thinking about having different sections that are linked that you can go and read more about and access further information. So, it’s more like there’s an editorial and then there’s a series of articles that you can read in different sections. And I think that’s where we’re kind of hoping to restart. Jared, I don’t know if you want to come in and say anything else.

WRAY: I think we are now thinking about it more like a kind of magazines style format, just ‘cause there’s so much. We originally wanted it to be a bit more like a long read, long form. And I think there will be a part of it, like a section that is still long form, and you can read it through as a kind of whole flow. But because of the complexity and interweaving between the gas disaster and water contamination, wanting to give space to survivor stories as well, we’re now thinking about having different sections that are linked that you can go and read more about and access further information. So, it’s more like there’s an editorial and then there’s a series of articles that you can read in different sections. And I think that’s where we’re kind of hoping to restart. Jared, I don’t know if you want to come in and say anything else.

STOUGHTON: Yeah. No, I think we felt that a single story was almost not sufficient to tell the length of, you know, to share the kind of, there’s so much here, and it sort of goes everywhere, and there’s so many things we’d like to be able to share. I think we still want to have all the kind of key story beats in one place, but we can, there’s a kind of opportunity to say, if you want to learn more, you can now go to this other resource and read more about this in a similar sort of format. But I think the great benefit of the platform we’re working with is that this scrolling setup means that it sort of is interactive in that when you scroll down, an image appears, there are things that fade in and out, and you can embed video, or you can have different ways to kind of keep someone entertained and engaged as they go through the piece. So, they’re reading, they’re getting the information, but there’s also something that will actually show them a diagram or a map or, you know, as well as the actual images themselves. Or images fade, or there’s parts of them that get revealed so that they really feel, you know, there’s kind of an ongoing process of learning as you go, but also hopefully enough that it keeps someone engaged and entertained throughout. I think it really is a challenge, but I’m hopeful that the content we have and the story is powerful enough that it really will draw people in.

SCHILLACE: It almost strikes me that there’s something to be learned from gameplay. Because I do feel like we are all, we like to achieve, like, levels. And so, in some ways, perhaps what appeals to us about these modular systems is a sense of completion. You’ve kind of like, “Ah, I’ve done that level.” And I’m not, I don’t actually play a lot of games myself, but I see how the current way we absorb media rewards you for sort of getting through it as opposed to slowing down. And so, teaching people to slow down is difficult. And one way gameplay does that is it has these little mini things that you can do, right, to get a set of points or whatever, and I think there’s some way in which we might be able to incorporate that. And perhaps the images that you’re developing are some of that, like, “oh, if I do this piece, I get this image that I can see, or I get the rest of the image. Maybe I only saw part of it before.” And so, yeah, it’s really, really fascinating. I’m really interested in the way this will come together. I can’t wait to see it when it’s all finished. Where can people learn more about what it is that you’re doing?

BARKER: Well, the LivingBodiesObjects Project website has bits of information about the project, and there’ll be updates on there about the work we’re doing together. For example, there was just, the BMA just hosted an exhibition at the Brighton Festival that included some of the artwork from the project. And we’re just about to put an update or a review of that exhibition up online. The BMA website itself is fantastic for anybody wanting to learn about the Bhopal disasters. There’s just an absolute wealth of information and storytelling there.

SCHILLACE: That’s fantastic.

STOUGHTON: Our website is on www.bhopal.org. And yeah, we’re currently running a campaign to fundraise for children, our children’s clinics. We also run a children’s clinic called Chingari. We provide physiotherapy, speech therapy, and education as well to children in the affected area. They can come and have a meal and see the other kids, and it kind of helps take some of the burden off those families who are still being affected by water contamination. So, it’s a really good cause.

SCHILLACE: That’s fantastic. And those of you who are listening, this always comes with a transcript and additional information on our blog, and the blog will also have links to the places where you can view this information. So, we’re so glad that you could all be here with us. Please check that out. I’m so glad you could listen. I’m so glad you guys could join us to be part of it. And is there anything you’d like to leave us with?

BARKER: Just that it’s the 40th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster in December, so there’ll be a lot of activity going on then, and hopefully our stories will be ready and published then. And yeah, check out the work of the BMA because there’ll be lots happening around that anniversary time.

SCHILLACE: Fantastic. Thank you. Thank you all for being part of the conversation.

STOUGHTON: Thank you.

BARKER: Thank you.

WRAY: Thank you.