Podcast with Tuen Toebes

In this podcast Teun Toebes reflects on how, as a 21-year old nursing student, he wanted to know more about the life of older people living with dementia in a care home in Utrecht in the Netherlands. Moving in as one of the housemate in a care home, and not as a nurse or a carer, Teun bonded with the residents, and learnt from them about love, care and dementia. After living for three and half years in two care homes, he documented his experience in ‘The Housemates’ a number 1 best seller book in the Netherlands. In the book, Teun critically analyses what a diagnosis of dementia entails in terms of stigma, institutionalisation and loss of autonomy for older people. He calls for change in ‘humanising care’ via a person-centred approach. Driven by hope, he believes that better quality of life for people living with dementia can be achieved when society, including carers and managers, residents, their family members, volunteers and policy makers work together in reframing the ethos of care. He also talks about the documentary film ‘Human Forever’, a global quest for understanding how dementia care is delivered outside the Netherlands. He sums up the key determinants of good quality of care in four themes; equality, inclusivity, dignity and reciprocation.

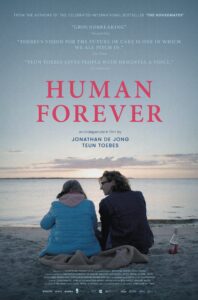

Teun Toebes (24) is a care ethicist and humanitarian activist whose mission is to improve the quality of life of people with dementia worldwide. As a nursing home resident for more than three years, he has experienced why this societal change is so badly needed, which is why Teun decided to take his mission to the next level by looking beyond Dutch borders for the documentary ‘Human Forever’.

Teun Toebes (24) is a care ethicist and humanitarian activist whose mission is to improve the quality of life of people with dementia worldwide. As a nursing home resident for more than three years, he has experienced why this societal change is so badly needed, which is why Teun decided to take his mission to the next level by looking beyond Dutch borders for the documentary ‘Human Forever’.

Dr Khalid Ali is the film and media correspondent at ‘Medical Humanities’, Global Health Film Fellow, founder of ‘Medfest Egypt’, an international short film festival exploring health and well-being, author of the book ‘The Cinema Clinic: Reflections on Film and Medicine’, and film maker. Dr Ali is a clinical academic; Reader in Geriatrics in Brighton and Sussex Medical School. He uses film as an educational tool to encourage medical students to consider a future career in Geriatrics.

TRANSCRIPT

[mellow music]

SCHILLACE: Hello, and welcome to the Medical Humanities podcast, the official podcast of BMJ’s Medical Humanities Journal. We invite you to listen in and join the conversation from global perspectives on health, medicine, and accessibility to interviews with social justice activists, filmmakers, artists, and academics from around the world. Stay up to date with public discussions that matter to medicine and humanities, because life happens at the intersections. [music fades]

SCHILLACE: Hello, and welcome to the Medical Humanities podcast, the official podcast of BMJ’s Medical Humanities Journal. We invite you to listen in and join the conversation from global perspectives on health, medicine, and accessibility to interviews with social justice activists, filmmakers, artists, and academics from around the world. Stay up to date with public discussions that matter to medicine and humanities, because life happens at the intersections. [music fades]

ALI: Hello, and welcome to this new edition of Medical Humanities podcast series. This is Khalid Ali, film and media correspondent at Medical Humanities. I’m also a clinical academic geriatrician at Brighton and Sussex Medical School. It gives me great pleasure and honor to welcome to this podcast Teun Toebes. Teun is a champion and an ambassador for older people, especially those living with dementia. Teun studied a degree in nursing followed by a degree in care ethics and policy. Teun also is the author of the book The Housemates: Everything One Young Student Learned About Love, Care and Dementia From Living in a Nursing Home. That was followed by him traveling around the world in a quest to understand how care for older people with dementia is delivered. He is also the passionate co-founder and ambassador for Article 25 Foundation. Teun, it’s a great pleasure to have you with us today. Over to you. Tell us more about how humanizing care for older people, especially those with dementia, came to be your calling.

TOEBES: Thank you so much, Khalid, for the invitation. It’s really a pleasure to bring you in touch with the hopeful message around dementia because it’s so badly needed that we change our view of dementia, that we get a more nuanced view on it. I was 21 when I finished my education in nursing, and I was working in a care facility on the closed ward of a nursing home. And I asked my colleagues, “Would you like to live here when you get diagnosed with dementia?” And most of the time the answer was no. So when I asked the family members of the people living in the nursing home, “Do you like to visit this place,” the answer was no as well. And when I asked the residents, “Do you like living here,” the answer was no. So, I was raising myself a question: How was it possible that we, as a society, created by all good intentions this system, which mainly focused on risk and control management instead of happiness of people, of quality of life? How is it possible that we created this? And why don’t we change it if we don’t want to live in it ourselves? So when I was 21, I decided to move into a care home on the closed ward to live together with people with dementia because my experience is that we don’t listen to people with dementia anymore. We think for them, and we organize a whole care system for them based on what we think they need, but we don’t listen. And we don’t ask the question, “What do you need to improve your quality of life?”

So, in total, I moved into the care home, and I lived there for over three-and-a-half years in two care facilities, first in Utrecht, in the center of the Netherlands. And after those two years I moved to Amstelveen, a bit below Amsterdam, because I wanted to experience are my experiences because of this specific house, or does it tell us more about a cultural perspective on dementia and how we look at care? And it’s definitely the last question. So, I’m really pleased to the fact that I’ve been able to live together with people with dementia, that I was able to build up really strong relationships with my housemates. But on the other hand, it was also quite painful because I came home every day in the nursing home with one big privilege. I had the code of the door, the code 2017, to leave. So I really felt the pain of this system of exclusion. And that’s why it’s so needed that we change our view not only in health care, but mainly in society. Because dementia is not a care problem, it’s a societal problem. It’s about the way we live together.

ALI: Indeed, Teun. And it’s a global health and social care issue that we all need to talk about and discuss. So you went in with a very inquisitive mind, moving in, not as a nurse or an assistant. You went in as one of the residents as you call them, your friends and your housemates. But you went in with the big why? Why are we doing this? So tell us about that approach to analyzing, investigating how care is delivered in the care homes that you stayed at, the big whys.

TOEBES: Yeah, and I think it’s really important to ask ourselves the question, why do we do the things we do them? If we look at care for people with dementia in the Netherlands, people mainly live at home. But in the last months of people’s with dementia life, they usually live in a nursing home. In general, people with dementia live over eight months in a nursing home. And in total there are almost 300,000 people living with dementia in the Netherlands: 50 to 80,000 of them are living in a care facility. So, the standard in the Netherlands is that we have a closed ward, and I believe that a closed ward is the ultimate product of exclusion. And it really tells a lot about our culture because we want zero risks in life. We don’t accept risks, but we have to accept that life, also a life from someone with dementia, comes with risks. But in my experience, this system of nursing home care was mainly focusing on…risk management.

ALI: Risk avoidance, yeah.

TOEBES: Yeah, exactly. So, that’s not what people with dementia ask. They ask for a good life and not for a safe life that costs what it costs. So, to summarize, in this care system, the urge for the collective safety weighs heavier than the individual quality of life. And that’s really a painful thing if we want to support the quality of life of individuals. So it’s about a collectivistic system, which doesn’t always have eye for the individual people with dementia themselves.

ALI: Teun, you’ve poignantly and very expertly analyzed your critique of the controlling system and hierarchy in care homes in the chapter Things Were Better in the Old Days. You refer to it as control freakery approach. Do you mind sharing with us reading a section from the book? Thank you.

TOEBES: Of course. No problem. It’s a part of Things Were Better in the Old Days. “The whole point of procedures and systems is efficiency. But the question is whether that concept has a place in care. We don’t produce hamburgers. It’s our job to provide customized care to people who all respond to and deal with their symptoms differently. How can you hope to apply a single model to them all? Especially when that model is designed to ensure that every puppet does what it’s supposed to do. It means that people who have been trained to help others end up on a bureaucratic treadmill of control freakery. It looks as if we make more of an effort to document everything in case something happens than to take a more human approach and actually prevent accidents from happening. I mean, when all the valuable hands-on staff spends more time in their office than on the ground, what could possibly go wrong?”

ALI: Thank you. And that’s the perspective of your criticism or your interpretation of the way we do things. But from in another part of the book, you refer to it as the feeling residents. Your housemates feel that they belong, and you refer to it as the art of seduction, that they’re seduced. The residents are not, they see this as their own home, and they belong. So, tell us about that art of seduction and the methods or the little things that you introduced into your housemates’ lives.

TOEBES: Yeah. Actually what was for me the most important was the experience that I was still able to build up a relationship with my housemates. And so often I heard from people of my age or from carers, “Why do you wanna live together with people with dementia? Because they actually forget immediately what you did.” But if we look at dementia like that, we exclude people because of their disease, because of what they can’t do. And I think that’s the most painful thing. So, my housemates, most of them, they didn’t remember my name, but they remembered the feeling we created together, the friendship we had. So, on Friday, we often had Friday afternoon drinks in my room, or we went out. We went, for instance, to a bar, or we went to the supermarket. We were enjoying the daily life every citizen of our society has. But when you live in a care facility, the relationship toward society changes. Actually, in my perspective, there’s no reciprocity anymore because people visit you in a nursing home, but you can’t go out because you are not allowed to go out. And that’s what we love to do: to go out and to enjoy the things we describe as little things. But if you live in a nursing home, those things are so big.

And personally, I really became aware of the role of the institutional environment because I was sitting in a nursing home, and as a carer, my first learning aim during my study was to be able to wash people. And now I think, how could that be my first learning aim? Because the first learning aim should be to sit in the living room, to live together, to listen, to feel, to hear, to smell, what do you hear, actually? In the nursing home, if you sit there, you constantly hear keys, for instance. And by the amount of keys you hear, you can hear who’s approaching, or it’s the coordinating nurse, or it’s the person living, working in the living room. So, it’s a symbol of power, a symbol of hierarchy. And if you really look at the organization of nursing homes, we really have good intentions, everyone. But good intentions only don’t lead to quality of life. If you really look at the system, it’s organized by the excesses of care and illness. And if the whole environment is organized like that, we can’t expect quality of life to be the ultimate goal. So, that really asks the difference. And it was so beautiful to learn from my housemates in this, because in the end, what I tell you now, it’s not something I designed in my mind. It’s something my housemates told me, but I am able to tell it to you now. My housemates unfortunately almost all passed away in the meantime, so I’m really thankful that I’m able to bring this message because it’s so needed that we change the view and the organization of health care.

ALI: And the message I think resonated with— We’ll come and talk about the international impact, beyond the Netherlands. But there’s two issues here I want to explore further with you. First is the carers in the care home, and some of them, especially young ones, you mentioned Niels, who come in with the best intentions. They want to do good, they want to care, they want to engage. But the system is not conducive or is not supportive of that humane, loving, caring approach of engaging, connecting. And there’s a lot of the paper filling and so forth. So, the attitudes change over time. So how did you navigate that, being a resident, but at the same time, understanding what carers who come in with a loving, caring, humane approach do change over time?

TOEBES: Yeah. I think Niels, the carer you were referring to, is a really beautiful example because Niels is an amazing man. He studied art, and now he’s working in health care. So he’s still creative in contact. And I always felt when Niels was working in the nursing home because my housemates were relaxed. My housemates were talking with each other. So it was a really social ambience, and that was so beautiful to experience. But on the other hand, I also saw the struggles Niels had with working in this care system. And the most easy thing to say in this cultural change is we need more money, we need more time, we need more staff, we need more. We live, as a Western world, we live in a culture of more. By default that if we have more, things become better. But that’s a false thought because it’s not always like that. It’s not always about more. It’s about the way we organize and the way we cope with the actual resources we have. So, by saying that the other has to change, for instance, politics or policy, we give the key to a better future to someone else. So yeah, we also, as carers, we have to believe that we can make a difference because this system, it’s not something which has been created during a Big Bang. It’s something which is the product of our culture in society, and that exactly makes dementia a cultural problem. And I really feel and believe that also my colleague carers, they really want a better future. But also, we as part of the problem, we have to change in that. We have to ask the questions, what do people want? And we have to prioritize around quality of life.

ALI: And I get a keyword that you mention here Teun, which is change. But you have, again, eloquently described that the catalyst for change or the drivers for change are actually the carers, but the residents, the housemates themselves, by being involved and engaging them in the day-to-day activities of doing the laundry together, preparing the table setting, being part of the daily routine. But doing it together brings those connections.

TOEBES: Yeah. But let us go a bit back, Khalid.

ALI: Mmhmm.

TOEBES: Because if we look at it from a more broad perspective, many people are scared about dementia. Many people feel anxious about the risk they have of getting diagnosed by it. It’s a risk from one in five in the Western world. So, we see dementia as a total loss of identity because we live in a hyper-rational world where your knowledge is the highest aim you could reach. So, we have to see a human being as more as only the rational capacities. And what we do in our Western world is that we created, from people with dementia, the other. But if we don’t see people with dementia as the other, but if we see people with dementia as a person like you and me, I really believe that if we see things differently, we will do things differently. So the human view is the fundament of this change. And if we really see people with dementia as people like you and me, we ask different questions. We ask questions: Is it normal to let people live on the closed wards? Is it normal to have a special toilet for staff and a special toilet for residents? Is it normal that we have different coffee for carers, cappuccino, and we have different coffee from the residents? We constantly make differences between a “We” and a “They.” But if we look at the vision on quality of life, we want to create a We. We have to care. We have to take care for each other. People with dementia can take care of us. I really learned a lot from my housemates. They gave me love, a lot of love. And I learned. They learned a lot of me. I was able to give them love. So it is about living together. And that’s the key of the message: that we have to live together with people with dementia again.

ALI: So true and so relevant. And you telling that in the fundamental aspects of where care homes are built, outside the—

TOEBES: Yeah.

ALI: So, tell me about your observations of the setting of care homes in the Netherlands to start off with.

TOEBES: Well, actually, it’s good to say that there are many other possibilities, and there are beautiful initiatives in the world who show that it is possible in this system to treat people with dementia more humane. It is already going on. There are huge ambassadors in the world. But in the Western world, the poverty of our welfare is the fact that we create institutions for people without asking them, “What do you need?” And those institutions are completely based on people’s disease. So, to give you one example, in the Netherlands, people with dementia receive a care indication, and the care indication is the ticket for a nursing home. Regular care indication for people with dementia for institutional care in the Netherlands, it’s around €100,000. If people become more sick, the nursing home receives a higher indication, so they receive more money. Then it’s €125,000. So, it’s a negative stimulus of €25,000 that if people become more sick, care organizations receives more money. It’s, for instance, the same in Belgium. If people are incontinent, or if people have a wheelchair, they have a higher care indication, so there is more money.

So, if we want quality of life to be the result, we have to change the fundaments of our health care system. And now, we completely divide people with dementia because of their disease. Also, if you look at what you mentioned, the place and the locations of nursing homes in society, it’s often outside of the city. And people are living them as a collective, as a group of sick people. And if we organize the system on people’s disease, we can’t expect the society to keep seeing them as the human being they are because then you are excluded by your disease. So, it is about more balance in our treatment of people with dementia.

ALI: It’s embracing the aging…

TOEBES: Exactly.

ALI: …course, the aging life course, without marginalizing or without putting them aside so we don’t see them, and we’ve done what we could as a society and as a culture. But there are, you also bring what we could do differently, the little things like changing the curtains, introducing some greenery around the place, plants. You talk about robotic dogs again. [laughs]

TOEBES: Mmhmm.

ALI: So, tell us about what we could do differently to enhance that homely feel of a nursing home.

TOEBES: Well, in the end, it’s also important to change the feeling from an institution to the feeling of being at home. But all those changes in nursing homes are changing, changes in the marsh because we have to change the fundaments. But if we want to change in the nursing homes, we could do a lot. For instance, why does every nursing home resident has a hospital bed while not everyone needs it? Why does everyone has an incontinence mattress, while not everyone is incontinent? I was the only person in the nursing home of all my 130 housemates who didn’t have a hospital bed. I was the only one with my own bed sheets. My housemates had the institutionalized bed sheets. I was the only one with my own towels. To give you one example, my housemates, they had the white towels, and they were like 80, 90 cm. And then there was written on it the name of the company which washes them. Could you imagine? You’re 80, 90 years. You have to dry your own back, and the towel is 80, 90 cm. You’re not able to dry your back by yourself, so you need help. And that’s exactly because this care system is organized by people’s dependency. We make people more dependent while it’s not always their needs.

And it also comes to that around, for instance, plastic plants. In the nursing home I lived, in the shared rooms, for instance, the living room, we only had plastic plants. And why? Because of a really good intention. Namely, people can’t eat plants, but there are also plants which are not poison for people. So, what we do is based on the good intention, we create a dead environment because we only have the fake plants. It’s not a question about money because the nursing home I lived did spend over €25,000 on fake plants last year. So it’s not about money, it’s about the way we organize. And we can’t expect life from people in the last months of their life if we let them live in a dead environment. So we have to create a living environment of nursing homes, and I’m really sure about the fact that we will see more life of people with dementia then.

ALI: Indeed, Teun. And it’s not only artificial environment, but it’s a restraining environment, in essence. And you refer to the restraining belts, the safety belts, the chemical restraints as well, the sedation and the antipsychotics. So, a lot to go through. But I’d like to move next to what do you want health and social care professionals to take from the book, The Housemates, your message?

TOEBES: In the end, my message is a really hopeful message because it is about the cultural change we could make reality. And my message is never a personal attack to carers, but it is about our culture. And we as carers, we are part of the problem, but we are also part of the solution. So what I want to do is to give people hope. And that’s really what is happening now, because, for instance, in the Netherlands, The Housemates sold over 70,000 times. It’s one of the best-read books of the Netherlands from the last years. So, a successful book about dementia is really rare because now, we mainly think dementia is only the law. So it is about a more nuanced picture, and carers are really a part of the solution. So, if we embrace the new vision on dementia and living together, then more hopeful future, more inclusive future will be more close than ever.

ALI: And congratulations on being the author of an international bestseller. But it’s such the need in people all different generations, care providers in the health and the social care sphere. From after the book and your three-and-a-half years in care home, in two care homes, you moved from the Netherlands globally. So tell us about Human Forever, the film.

TOEBES: Yeah. Together with my good friend and filmmaker Jonathan de Jong, I traveled around the world to around 11 countries in four different continents to see how we treat people with dementia now and what we could learn from different cultures. So, what we did, Jonathan and I, is that we spoke with over 35 countries, from researchers to visionaries to people with dementia, and we asked them, “What is a good life for you?” And in the end, we visited all the 11 countries, we visited the four different continents, and what we saw was a really hopeful message around dementia. Because of course, dementia can be really painful, but what is more painful, if we listen to people with dementia, is the way how society treats them, the way they are stigmatized, or the way people feel excluded. And that’s really an experience of people with dementia, what they told us and what we should take serious. Because on the one hand, it’s a really painful conclusion. But on the other hand, it’s really hopeful because the way we treat people is something we could change.

So, for instance, we saw good initiatives all around the world. We went to South Africa, where there are no nursing homes. So people with dementia are living in the society like part of a community. In North America, we visited an intergenerational school where elderly, including elderly with dementia, were teaching pupils around language and mathematics. What was amazing because they didn’t label people with dementia as a dementia patient. They didn’t tell the pupils she or he has dementia. No, there was no stigmatization. In South Korea, we visited places where the prevention of dementia is a key priority of the government, which is a really hopeful message for other countries. But also in the Netherlands and a bit closer in Europe—in Belgium, in Switzerland, in Moldova, in Slovenia—we visited beautiful places. And yeah, we are very thankful that we are able to tell this message because it’s so needed that we change our narrative, and a film really helps in that.

ALI: Indeed. So tell me about the impact of the book and the film. I know that it was not your intention to change policies or laws or regulations, but you managed to get to several encounters with senior decision makers, Mark Rutte, for example. So tell me about how you moved on from those personal experiences to a different platform.

TOEBES: Yeah. And I really get your question, because I started living in a nursing home because I deeply felt worried, and I just love contact with people with dementia. But since I was living there, there came more attention, and people felt the urgency to change our way of treating people with dementia. So, in the end, what I really want, and what Jonathan and I really want, is that we want change. And to change, we have to reach everyone, people in society. We have to reach politicians. We have to reach policy makers. We have to reach the health care insurance. We have to reach the care inspection. We have to reach the bakery. We have to reach everyone in society. So, that’s what we are busy with now. I’m often speaking with leading decision makers and politicians all around the world. So, that’s really a beautiful to do. And I don’t have anything to lose. The only thing I have to win is a societal change, and that’s really something what gives me hope and what strengthens me to make this mission to improve the quality of life a reality. Because what we heard during the research from all the countries, also from Belgium, for instance, or from the UK, is why are you coming to visit us while you are from the Netherlands? What do you want to learn from us? Because you in the Netherlands, you have the best care system in the world.

And on the one hand that’s a really comfortable position because, yeah, if people think you are the example, you can close your eyes from improving. But on the other hand, it’s really dangerous. And I think there’s kind of a reality in it because we have a good quality of care. But that’s exactly the problem in the way we treat people with dementia. Because also during my college and also in the actual approach towards people with dementia, quality of care is the highest aim. Quality of care. But if we listen to people with dementia, and if we as carers are more humble, the highest aim shouldn’t be quality of care, it should be quality of life. And quality of care is crucial to facilitate quality of life, but if quality of care stays the ultimate goal, then people keep having the feeling that they are made a patient. And that’s what actually no one of us wants. We don’t want our life to be led by a care plan, for instance, by a diagnosis, by a care indication. And that’s really what we could change. And therefore, everyone in society, all decision makers, are needed. So, speaking with a lot of people, yeah.

ALI: And you’ve nicely summarized it towards the end. But this is a personal cry from the heart, one of your chapters. It’s a cry from the heart to challenge, to look at the way we deliver things, and I say the collective we, differently. And I take your point about moving from, to a wider, more holistic person-centered approach to quality of life.

TOEBES: Mmhmm.

ALI: I’d like to ask you—we’re coming towards the end now—about what’s next in your mission as an ambassador and champion of older people and their families affected by dementia? What’s in the pipeline?

TOEBES: The mission continues. So, after three-and-a-half years of living on the closed ward, I don’t live on the closed ward anymore. And why? Because the message is not about nursing homes. The message is about the way we organize our society, the way how we could create a more inclusive society. So we have to create communities, and that’s where I’m busy with now to keep learning from people with dementia. We will continue with the film all around the world. So we will go to many countries, we will speak with decision makers over there, and we will continue the mission. And I’m really hopeful for the future, and that’s really what I wish everyone to feel. Because when we are speaking about care for people with dementia nowadays, I often don’t feel and hear hope. Sometimes it feels for me, as a young person, that we are okay with the way we treat people with dementia now, that we think it’s normal to have nursing homes, or that we think it’s normal to have closed wards. And this change are something from all of us. So yeah, I will continue to bring everyone in touch with this vision and this mission because then, we create a better future. In the end, a better future for people with dementia is not only a better future for them, it’s more a better future for us all.

ALI: Absolutely. I can’t agree with you more. Maybe I’ll say you’ve summarized it again beautifully in your four key messages at the end of the book: equality, inclusivity, dignity, and reciprocation. So these are four key themes that set the foundation to a different approach to envisioning care and delivering care. So, Teun, thank you so much for being so generous with your time. I know you’re very busy with the work on the ground, working with people and families, but as well as advocating in the Netherlands and globally for better human care, humanizing care for people with dementia. So, thank you so much for your time and for the great work that you’re doing for all of us, as in health and social care providers, but as in the future, people who we will, as you mentioned, one in five will be affected by dementia worldwide. So, we are investing in our future somehow. So thank you ever so much.

TOEBES: My pleasure. And thank you so much. In the end, we shouldn’t forget if we keep seeing the human being, he will never disappear, and that’s really something we could learn from people with dementia.

ALI: Human forever. Thank you very much, Teun. Thank you. [mellow music returns]

SCHILLACE: Thank you for listening to the Medical Humanities podcast. Since 2020, transcripts are available for all shows on our blog. Stay in touch by reading the Journal and blog online. Just follow the links in the episode description. We are also on Twitter as MedHums_BMJ.