Blog by Tina Chai

When asked my age, I almost always want to say sixteen before stopping myself to say twenty-four. I don’t feel twenty-four. At most, I’m twenty-three and three-fourths—oscillating between who I was and who I want to become, but not feeling quite there or quite good enough. Sometimes, I say something foolish to an attending physician, and that’s when I’m nine. Occasionally, all I want to do is sleep, and that’s the two-month-old part of me.

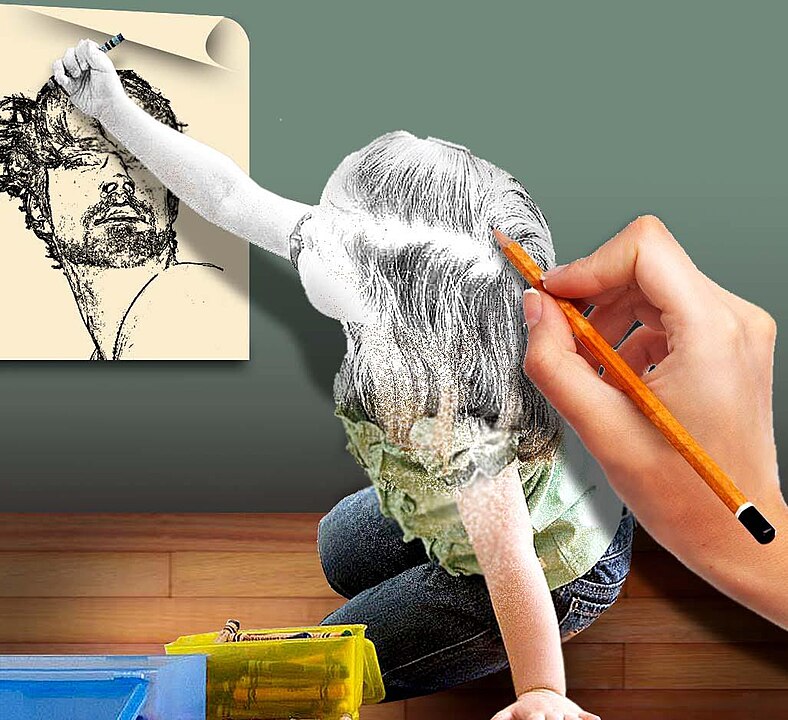

When I met “Zoe” in my adolescent medicine elective at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, she was seventeen but let her inner thirteen-year-old shine. Maybe she didn’t think she would make it to seventeen because she was born at twenty-five weeks with a host of medical concerns that contributed to developmental and behavioral delays. She sat cross-legged on the floor and with crossed arms, between the examination table and the wall, only repositioning to curse at her mother or to curtain her face with her dark curly hair. She refused everything offered. Heart and lung exam? “No!” Meningitis vaccine before college? “No!”

Zoe’s mother wanted to address her daughter’s social anxiety. Zoe refused to eat at school, much less talk to her classmates and teachers. She had been prescribed medication three years ago. For a while, her mother thought she was improving, but then found little white pellets scattered across the bottom of her bed, mixed with dust, tissues, and marbles. Zoe had refused to take the pills, just as she had refused to utter a word to her ex-therapist, just as she refused our care today.

I sat in quiet observation, recalling Robert Frost’s poem about the end of the world, “Fire and Ice.” Zoe a ball of fire, hissed curses and threw embers of “No!” into the room. Zoe’s mother, serene and cool, battled the inferno with gentle rains of “Sweetie, how about another chance?” No one was winning this duel, but Zoe’s mother gave no sign of frustration other than her scrunched lips, reminding me of my own mother’s reserve when I ignored her parenting. The light in Zoe’s mother’s brown eyes and the wrinkles hugging her cheeks signaled provisions of patience. Her hair was thick like Zoe’s but tamed with a straightening wand and highlighted by ivory streaks. Was I looking at a version of Zoe, thirty years into the future?

I remembered being Zoe’s age in high school, constantly going against my mother, feeling every emotion yet unable to control any of them. Perhaps Zoe’s mother had also learned patience through raising her daughter, hiding her frequent worries; and perhaps Zoe, too, would learn the extent of these worries at nineteen, seeing her mother cry for the first time.

I brought my attending physician into the room. I stood and she sat above Zoe in a chair as we offered treatment options. How about talking to someone again? “No!” Medication to calm your nerves? “No!” Your anxiety is not your fault. We want to help you and your brain. “No!” Okay, we won’t do anything you don’t want.

Nothing seemed right after we stepped out of the room, and the stubborn sixteen-year-old part of me broke through. I asked my attending’s permission to go back alone and talk to Zoe; she agreed.

I wanted to tell Zoe that she may never feel seventeen; that on a good day, she may only feel sixteen and three-fourths; that her anxiety might make her feel nine; that some days all she’ll want is to sleep like a two-month-old; that we want to work through this crippling social anxiety with her. But if I put on my “future physician” hat, trying to be as forty as I could, I knew Zoe wouldn’t budge.

We sat, eye to eye, on the floor. She whispered undiscernible phrases under her breath, and I whispered back, trying to emulate the softness of her mother, of my mother, telling her that giving counseling and medication another chance would help her feel better. Zoe held her breath, fiddling with her shoelaces. The end of our conversation seemed indefinite. Then, smoothing her bangs behind her ears, she whispered, “No,” but also smiled.

I left Zoe and her mother with the clinic’s number, feeling so twenty-three and three-fourths—but that was good enough. Zoe’s pause, her softer “No” and smile, indicated a small change of mind. Change happens in baby steps, as we quietly build trust with our patients so they may listen and take advice. Sometimes we can’t ask more. Yet we also ask a great deal of ourselves. As physicians-in-training, we constantly oscillate between ages, maturing and regressing, hiding our worries about not being good enough for our patients. Just as we gift our patients the space to keep trying, we should extend a similar grace to ourselves.

Tina Chai is a third-year medical student at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, TN. She earned both a BS in biochemistry and a BA in English from the University of Virginia.