Podcast with Cindy Weinstein

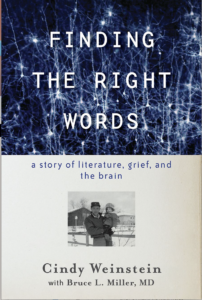

In this episode, we get to speak with Cindy Weinstein, co-author of FINDING THE RIGHT WORDS, a memoir about losing a parent after a ten-year struggle with dementia. Weinstein is the Eli and Edythe Broad Professor of American Literature at the California Institute of Technology, where she has taught and written several academic books since 1989, including Time, Tense, and American Literature: When is Now? (Cambridge, 2018). Most recently, she has published, with Dr. Bruce Miller, Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief, and the Brain, a prize-winning dual memoir that focuses on Cindy’s father, Jerry, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1980s. In order to write the book, which combines autobiography, literary criticism, and neurology, Cindy studied neurology at UCSF’s Global Brain Health Institute, attending classes, grand rounds, and differential diagnoses, reading memoirs, and drafting her book with Bruce. Chapters go back and forth between Cindy’s voice and Bruce’s, with Cindy describing her father’s “clinical presentations,” including word-finding difficulties, spatial disorientation, and behavioral changes, which Bruce then discusses from a neurological point of view. The two cultures, as C.P. Snow described them years ago, are bridged, as the humanities and sciences come together and harmonize. Finding the Right Words is told in this way in order to describe the complexities of grief, to disseminate Bruce’s knowledge of neurology, to share Cindy’s expertise in and love of literature, and, most importantly, to honor the deep humanity of a beloved father.

In this episode, we get to speak with Cindy Weinstein, co-author of FINDING THE RIGHT WORDS, a memoir about losing a parent after a ten-year struggle with dementia. Weinstein is the Eli and Edythe Broad Professor of American Literature at the California Institute of Technology, where she has taught and written several academic books since 1989, including Time, Tense, and American Literature: When is Now? (Cambridge, 2018). Most recently, she has published, with Dr. Bruce Miller, Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief, and the Brain, a prize-winning dual memoir that focuses on Cindy’s father, Jerry, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1980s. In order to write the book, which combines autobiography, literary criticism, and neurology, Cindy studied neurology at UCSF’s Global Brain Health Institute, attending classes, grand rounds, and differential diagnoses, reading memoirs, and drafting her book with Bruce. Chapters go back and forth between Cindy’s voice and Bruce’s, with Cindy describing her father’s “clinical presentations,” including word-finding difficulties, spatial disorientation, and behavioral changes, which Bruce then discusses from a neurological point of view. The two cultures, as C.P. Snow described them years ago, are bridged, as the humanities and sciences come together and harmonize. Finding the Right Words is told in this way in order to describe the complexities of grief, to disseminate Bruce’s knowledge of neurology, to share Cindy’s expertise in and love of literature, and, most importantly, to honor the deep humanity of a beloved father.

Link to the website for Finding the Right Words.

Link to the images for Finding the Right Words on the book’s website.

Listen to the podcast below:

Transcript

BRANDY SCHILLACE: Hello and welcome back to the Medical Humanities Podcast. I’m Brandy Schillace, your host and Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Humanities Journal for BMJ. Today I’m very excited to be talking to Cindy Weinstein. She, with coauthor Bruce L Miller, wrote a book called Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief, and the Brain. The story is of an English professor studying neurology in order to understand and come to terms with her father’s death from Alzheimer’s. So, Cindy, welcome. So glad to have you here today.

CINDY WEINSTEIN: Thank you, Brandy. It’s really nice to be here.

CINDY WEINSTEIN: Thank you, Brandy. It’s really nice to be here.

SCHILLACE: Could you tell us a bit about yourself and first of all, a little bit about who you are and where you’re coming from and how you ended up coauthoring this book.

WEINSTEIN: Sure thing. My name is Cindy Weinstein. I’m an English professor at the California Institute of Technology, which is where I’ve had my entire career. And my area of literary criticism is directed toward US literature, primarily the 19th century. And my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1980s, when everything was Alzheimer’s that involved forgetfulness. There weren’t the sorts of distinctions that thankfully are being made today under the larger category of dementia. And I wanted to write a book to, as you said in the introduction, come to terms with the diagnosis and the fact that my father’s first clinical presentation, as it’s called, was word finding. And he couldn’t find words, and this was what I had an extraordinarily difficult time with, because I was becoming an expert in language. I was getting my Ph.D. in literature at Berkeley at the time that my father was losing words. And it was that synchronicity that I needed to work through in some way. Go ahead.

SCHILLACE: Yeah. I can understand that. No, I was just gonna say that words are how we think a lot of the time.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: And I don’t think we realize how much. I actually, I had temporal lobe epilepsy seizures when I was in college.

WEINSTEIN: Oh, wow.

SCHILLACE: And I used to get aphasia and dysgraphic disorder. And I remember thinking, I remember how I couldn’t, I didn’t know how to think without words. It was, it’s very, very hard for us to understand how to function without words, because we’ve become a species so dedicated to their use.

WEINSTEIN: That is so true. And one of the ironies—just to kind of fast forward a little bit, and then I wanna get back to writing the book with Bruce Miller at UCSF—but one of the ironies of writing the book is as much as I love language, and Finding the Right Words is a kind of love letter to words and novels and an expression of how much I loved my father, language isn’t necessarily all it’s cracked up to be.

SCHILLACE: Mm.

WEINSTEIN: And there are other forms of communication that sort of people now working in the dementia space are thinking about, and that gives me some comfort. I mean, words for me and for most of us, as you say, are really where it’s at, but feeling and touching and music and dogs and animals—

SCHILLACE: I hear a dog. [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: I mean, there are all sorts of ways to make— Yeah, yeah. We just got one actually at the rescue a couple days ago. [laughing] So, we’re in the middle of training him. But in any case, I wanted to write this book. There are a lot of really wonderful books about dementia and more specifically, my father—I learned from Dr. Miller, I’ll call him Bruce—my father actually didn’t have Alzheimer’s exactly. He had early-onset Alzheimer’s, which means 65 or younger, early-onset Alzheimer’s with what’s called the logopenic variant. And that is the word finding issue. Now, of course, Bruce, we didn’t have PETs or MRIs. I tried to get them, but the office in DC didn’t have them anymore. So, Bruce, it’s a speculative diagnosis, but it sure explained a lot.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: And because there are lots of books about Alzheimer’s and dementia more broadly, I wanted to write a memoir that was not just my own story and my father’s story. I honestly didn’t know how resonant the story would be of a Jewish, New Jersey, middle-class girl goes to Berkeley for a PhD. I just didn’t know if that would connect. And what was really important was I work at Caltech, and not everybody thinks about the world through the lens of Moby-Dick and The Scarlet Letter and the….

SCHILLACE: But I do though. [chuckles]

WEINSTEIN: [laughing] But I do! Always, always. Right. Exactly. But like science, you know. So, I was like this intuitive part of me thought geez, I’ve only gotten so far in dealing with my grief through the tools that I have to understand the world, which are the love of a daughter and literature. Maybe science would help. And so, I ended up applying to an interdisciplinary program called The Global Brain Health Institute, which is in the Neurology Department at UCSF, and also at Trinity College there’s a location. And Bruce and I worked on the book together. I learned enough neurology to set the table, as it were, for Bruce to come in and reflect on the clinical presentations that I describe, whether those are word finding, spatial disorientation, behavior, memory. So, it’s a kind of call and response back and forth between me and Bruce. And Bruce’s expertise, not everyone has access to UCSF. A lot of people don’t, whether it’s UCSF or the Penn Memory Center or Mayo Clinic. And it was really vital for me to try and give readers access to the best science out there, and that’s Bruce. So, that’s how the book came to be.

SCHILLACE: That’s really fascinating. I think for me, memory is such— I’m hyperlexic. I’m autistic and hyperlexic. I have been accused of having a photographic memory. I don’t. There’s not really any such thing in the way people talk about it. But I do have an excellent memory, and therefore there’s probably nothing that frightens me more than the idea that I wouldn’t be able to access those memories.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: But then again, I mean, some of the things that you talk about and that I know Bruce Miller talks about is we have a tendency to privilege memory in ways maybe it doesn’t always deserve either.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: We are not necessarily just our memories.

WEINSTEIN: Right. That is so true. You raise many interesting points here. I’m thinking about Ann Basting’s work, Forget Memory. And she is a, I think a MacArthur fellow, and she’s done this practice where she goes into senior centers, and they put on plays. And it doesn’t matter if one thing follows from another. [chuckles] It just doesn’t matter. It’s about the process, and it’s about the present tense. But like you, I am sort of deeply committed to my memory. And I should say, just in terms of the book, I had thought initially when I started that the book would begin with memory ‘cause my understanding was that Alzheimer’s was only about memory. But that’s not true. It’s got many more components, and many more brain networks get assaulted by Alzheimer’s. And so, what I thought was gonna be the first chapter, memory, ended up being the last chapter. Part of that was because that was the hardest chapter for Bruce to write. And also, it turns out that one of the things I discovered in the course of writing the book was that I hadn’t forgotten memories of my father. And the memories I’m talking about are memories of my healthy father.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: But I had kind of stored them away, really, really far away, because it hurt too much to remember him when he was healthy.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: And so, the process of writing the book, strangely, allowed me to remember all of the happy things ‘cause I had like 25 years with my healthy father. And so, the last chapter is a kind of—this is very grandiose, but I think you’ll appreciate it—a kind of catalog of memories of my dad. Like, I was thinking Whitman. I love Whitman. And just sort of stream of consciousness and getting back to the happy memories was, I think, really important. And one of the other things I discovered was this disease has a very strange mirroring effect. So, one with Alzheimer’s losses memory. I lost some memory of my dad. Some of the spatial disorientation that my father experienced, I was in Berkeley, but completely disoriented. And so, this very strange mirroring effect started happening, which when I’ve spoken with other people with family members with dementia, say that that is not all that unusual, especially being unable to remember the good stuff because the diagnosis is so difficult.

SCHILLACE: Well, so, I’m a [laughs] I hesitate to say expert, though I’m sometimes called that. I study death and grief a great deal. My first book was about grief cross-culturally and historically, and I ended up talking a lot about grief during COVID-19 for the New York Times and other places, NPR, people wanting to say, “How do we deal with this now? What’s happening now? Has grief changed?” And one of the things that occurs to me is that when you are dealing with an illness like Alzheimer’s, what you have is anticipatory grief for losses you haven’t experienced yet. And so, we’re really bad with that.

WEINSTEIN: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: We don’t know how to deal with anticipatory grief. It’s not something we talk about. Even the kind of stages of grieving are all for after the fact. We don’t talk about the in-between.

WEINSTEIN: Right. That is so true.

SCHILLACE: And now you have people suffering from long COVID, or my best friend, Arabella Proffer, she’s an artist. She has terminal cancer. Dealing with knowing a thing is gonna happen, but it hasn’t happened yet, we all behave as though we’re walking around without the grief, when in fact we’re experiencing it.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: We experience it on both sides. And I’m reading, next year for The Peculiar Book Club, we’re also doing Lauren Aguirre’s The Memory Thief.

WEINSTEIN: Oh, great.

SCHILLACE: Yeah. Which is about damage to the hippocampus and a peculiar kind of amnesia. But the interesting thing, as you were talking, I thought Alzheimer’s is a memory thief, not necessarily for the Alzheimer’s patient.

WEINSTEIN: Right. Right. Right. You raise so many good points here. I tried to be rational about my grief, which was [laughs]….

SCHILLACE: Ah. [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: I try and tell myself it was the best I could do. I was 25. But when I say that, I mean, like, okay, my dad in the days when you had to load film in a camera, he loved to take pictures. Okay. Am I gonna lose it when he can’t do that?

SCHILLACE: Mm.

WEINSTEIN: What am I gonna do when he can’t do this other thing that I think? And so, I tried to sort of hide in my intellect and the compartmentalization. Again, it’s how I got through my Ph.D. It was the best I could do. But what ended up happening, and I say this in the book, is I kind of gave myself an anesthetic that took a very, very long time to wear off.

SCHILLACE: Mm. Mmhmm, mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: And I think what you’re describing, the anticipatory grief, I just couldn’t do it. And the duration. And I think COVID-19 is probably a really good analogy. It’s the duration of, maybe it’s all grief. I don’t know. But my dad, the death just took forever.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: And so, I remember at a certain point, I thought, okay, our life together is going to the nursing home. Like, whenever I go to Florida to visit him, that’s what we’re gonna do. And then when my brother called to tell me that Dad was dying after over a decade, it was like I was hearing it for the first time ‘cause I forgot that he was dying.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm! Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: It was the strangest thing, Brandy. It was so weird. And so—

SCHILLACE: I have heard stories like this. I mean, one thing I will say, and I’m not necessarily saying it to you, though I’m also saying it to you, but to our listeners, you cannot do grief wrong. There’s no right way, you know?

WEINSTEIN: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: So, it’s always about approaching it the way you can approach it in the moment at which it’s happening. And so, one of the things that you said earlier, which I think is really valuable and is a part of what you and Bruce do in the book, is talking about the power of the present, the power of making something together, even if we can’t make it stay. There’s a, I don’t know how familiar you are with Sesame Street, but when I was a child, very, very young child, again, I’m hyperlexic. I’m autistic. I have a really clingy memory. But there was a little cartoon that they did where a girl liked to draw pictures, but she didn’t know where to put them to keep them safe. And in the end, she decides to just let them go away because it doesn’t matter. She made them.

WEINSTEIN: Wow.

SCHILLACE: And I remember I was about four years old, and I was just completely like, wow! You know, it was mind blowing. And I still recall that because I think the act of being there in those moments in making them is more important than the recording of them. And I think we’ve tended to forget that in our digital age where we record everything.

WEINSTEIN: Right. Right. I think one of the complexities can be when one is far away. And so, that was my situation. My mother was the primary caregiver. I knew that there was no way on earth that either one of them would’ve wanted me to give up what I wanted to do, and so I didn’t. And sort of living with that decision has been a challenge. And what’s been helpful is to think about moving, moving the feelings of guilt over to ones of regret, which is a little gentler as well as what you’re saying, like there’s no right way to do it.

SCHILLACE: No, no, there isn’t. And in fact, while dying is something we all do, death is for the living. Death and dealing with it, that’s something the living do.

WEINSTEIN: Yeah. Right.

SCHILLACE: And in a way, as your father’s memories began to fail, you took on more and more of that same burden. So, do you understand what I mean?

WEINSTEIN: Yeah. I do.

SCHILLACE: It’s like you were taking on aspects of that before you lost him.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: And to me, that is both the power, the grief, the tragedy, and the blessing of extensive, slow dying, I guess you might call it. It’s awful and wonderful.

WEINSTEIN: Yeah, that’s so true. In fact, it makes me think in my first book based on my dissertation, the epigraph was, “To my mother and father, whose memory is safe in mine.”

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

WEINSTEIN: So, that really captures what you’re describing, I think. So, the good news is the readers seem to be responding to the book. I think for some people it’s a little too hard to read, especially my sections.

SCHILLACE: Mm.

WEINSTEIN: Bruce’s are just amazing in terms of explaining the science in a way that general readers, i.e., yours truly, can understand. And what I also like about his contribution is that he uses my father’s situation as a kind of departure point, but then expands to talk about other kinds of dementia. His area of expertise is frontotemporal dementia, which is very behavioral in presentation. But there’s also ALS. There’s [Creutzfeldt-Jakob]. There’s all sorts of dementias. And Bruce explains many of them, as I said, using my father’s illness as a departure point.

SCHILLACE: I think just to, you know, here we are. We’re at the Medical Humanities Journal, and I do medical humanities more broadly. I’m also a writer. I write both non-fiction and fiction. And my degree of expertise was in 18th-century literature and then later in medical history. So, I have a very sort of intersectional kind of look at these things. And you say something which is absolutely true. We do have an easier time reading the science. We’re sort of like, “Okay, STEM, STEM, STEM, safe. Safe.”

WEINSTEIN: Right, yeah.

SCHILLACE: But to be honest, it’s because the humanities, the word “human” being in there, very important, the humanities speak to our soul. They do.

WEINSTEIN: Right.

SCHILLACE: They cut us because that’s why I, you know, I very rarely cry during a science documentary, but I can weep openly at television and movies and things like that.

WEINSTEIN: That’s so interesting you say that because one of the things I write about, I explain why I’m writing this book about my father with someone else who never knew my father except through my memories. And I write that when I’m talking about Edgar Allan Poe, I’m not crying, but when I’m writing this other thing, I am. Although, I should say that Moby-Dick plays a really important role throughout Finding the Right Words, because I spend a lot of time talking about identifying with various characters and rage and things like that, so.

SCHILLACE: Moby-Dick is actually my favorite book.

WEINSTEIN: Yay!!!

SCHILLACE: Frequently when people ask me if I was on a desert island, what book would I bring? And I’m like, “Well, this one has a lot about whales,” [laughs] but it’s a really wonderful book. Every student I ever, I used to be in academe. I’m not now. I’m freelance, and I’m a public intellectual. But when I was, I’d teach Moby-Dick, and the students always hated it [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: Oh, really? Oh, that’s—

SCHILLACE: But mostly because they thought it was a book about a whale. And I had to always explain it’s not. [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: Yeah. I’m actually teaching it right now, and the students, they’re Caltech students. So, oftentimes they’re going against the grain to begin with.

SCHILLACE: Mm. Right! [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: But many, many of them are just giddy with reading it. It’s so interesting.

SCHILLACE: I love it.

WEINSTEIN: Yeah, yeah.

SCHILLACE: There’s a whole the whole passage about the castaway chapter. Sorry, I know we’re getting off topic, but the castaway chapter.

WEINSTEIN: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: Just all of you listeners need to go find online the castaway chapter of Moby-Dick and read about these subterranean coral insects, who from the firmament of waters lifted colossal orbs. You need that. You need that sentence. [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: Oh! Beautiful. I love it! That’s great. That’s great.

SCHILLACE: End of book is great. And so, we’re wrapping up now. But I have to say, I could talk to you for ages about this material. I think both memory, Alzheimer’s, grief, these are areas where the medical humanities really shine because it’s a confluence of medicine, science, the humanities, history, social justice, access, health care. So, I’m really pleased. And I’ll just give the book’s title again for anyone who might have missed it earlier. It is called Finding the Right Words. It’s called Finding the Right Words. Cindy and Bruce both coming together to talk about it from the humanities and from science, and I know all of you will really, really enjoy it. Cindy, is there anything you’d like to leave us with today?

WEINSTEIN: No, just many thanks and just loving the quoting from Moby-Dick.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

WEINSTEIN: And I could talk to you for a long time as well, but this has just really been an honor. Thank you so much, Brandy.

SCHILLACE: Thank you. And for all of you listeners, as I say at the end of every show, thank you for being part of the conversation.