Book Review by Laura Grace Simpkins

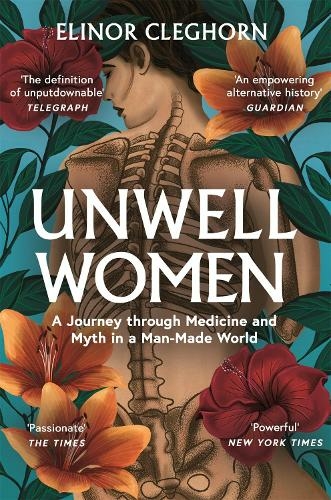

Elinor Cleghorn. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 2021. ISBN 9781474616850

Anne Green joined a grand house in an Oxfordshire village as a scullery maid during the 1640s. She was raped by the owner’s nephew in 1650 and became pregnant. Four months later, Anne went into labour. Her son was stillborn and she buried his body near a cesspit. Soon, he was discovered. Anne was put on trial for attempting to conceal the death of an illegitimate infant, which she was found guilty of, and was sentenced to hang. After Anne was pronounced dead she was taken to the anatomists who had been permitted to dissect her body. When her coffin was opened, Anne appeared to be breathing. To put her out of her misery, a male servant stamped on her. The next morning, the anatomists heard a whisper from Anne’s throat. ‘She had been hanged, stamped on, and lay in the cold for hours. But she wasn’t dead’ (70). Ann was revived by the anatomists and later retrialled. Ultimately, Anne was pardoned. It is likely she wouldn’t have been without the testimonies provided by the male anatomists who concurred with the local midwife and fellow servants that Anne’s pregnancy was in its early stages; that the baby would have not been able to survive under any circumstances.

Anne Green joined a grand house in an Oxfordshire village as a scullery maid during the 1640s. She was raped by the owner’s nephew in 1650 and became pregnant. Four months later, Anne went into labour. Her son was stillborn and she buried his body near a cesspit. Soon, he was discovered. Anne was put on trial for attempting to conceal the death of an illegitimate infant, which she was found guilty of, and was sentenced to hang. After Anne was pronounced dead she was taken to the anatomists who had been permitted to dissect her body. When her coffin was opened, Anne appeared to be breathing. To put her out of her misery, a male servant stamped on her. The next morning, the anatomists heard a whisper from Anne’s throat. ‘She had been hanged, stamped on, and lay in the cold for hours. But she wasn’t dead’ (70). Ann was revived by the anatomists and later retrialled. Ultimately, Anne was pardoned. It is likely she wouldn’t have been without the testimonies provided by the male anatomists who concurred with the local midwife and fellow servants that Anne’s pregnancy was in its early stages; that the baby would have not been able to survive under any circumstances.

Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World by Elinor Cleghorn is a revised history spanning from the ancient Greeks to the present day, one which places women at the centre of medical discovery, knowledge, and practises. In the introduction, Cleghorn declares that medicine is ‘androcentric’: it assumes male bodies are the standard by which to measure all against and that medicine holds male-dominated forms of knowledge in the highest regard. The harrowing tale of Anne Greene distils for us the key conflict Cleghorn highlights in her book: women’s lived experience of their bodies versus men’s learned mastery over them. As Cleghorn writes: ‘Between the anatomists, the midwife, and Reade’s [the owner’s] domestic staff, different forms of knowledge about the female body tussled for legitimacy during Anne’s trial’ (72). Cleghorn’s overarching aim, illustrated by Anne’s tribulations and throughout, is to unearth women’s experience about their bodies as well as to educate readers about the predominantly female activists, doctors, and everyday human beings who fought and continue to fight misogyny, racism, and other oppressions at play within conventional medicine. As such, she focuses mainly on UK-based histories, and briefly touches on issues in western Europe and North America.

Each chapter spends time with one or more of the ‘female illnesses’ which have been routinely medicalised and often pathologised. These include MS, fibromyalgia, vaginismus, PMT, menstruation, pregnancy, fibroids, menopause, autoimmune issues, and chronic fatigue syndrome. Cleghorn assuredly charts the rise and sometimes decline of these different diseases, mapping out where they surface and also, fascinatingly, when the site of illness transforms. Cleghorn pinpoints the organs responsible for ‘women’s troubles’–the uterus, the clitoris, the ovaries, the central nervous system, hormones, the ‘gendered brain’, and the immune system–and reveals how one organ succeeded the other in the collective imagination of male-dominated medicine. According to Cleghorn, it was the uterus that kicked off the chain, a mysterious muscular organ which ‘On the one hand…defined women’s divine purpose as hosts to the organ of creation. But, on the other…was an unruly cauldron, constantly brewing disorders that disturbed ideal feminine states of body and mind’ (57). Although Cleghorn doesn’t make this link herself, her work on the mutating seat of female pain and disease reminded me of academic publishing on this topic, in particular Amy Lunn Koerber’s From Hysteria to Hormones: A Rhetorical History (2018).

Cleghorn admits up front that her book prioritises women’s history–as in cis women’s history. She is passionate about diversifying the field and is resolute that work on how other sexualities, genders, and identities are systemically oppressed by androcentric medicine will come. And, although I understand her decision to pit a straight cis man/woman binary (this research is ‘new’, why complicate it further?) , perhaps Unwell Women, in excluding such stories of queer, trans, and gender non-conforming people, especially those from ethically diverse backgrounds, until they can be told ‘properly’ simply just avoids telling them altogether and results in a flat, homogenising narrative. On the very first page Cleghorn writes ‘At every stage in its long history, medicine has absorbed and enforced socially constructed gender divisions’ (1), yet doesn’t do a huge amount to complicate that picture in her book. With that said, Unwell Women is undoubtedly a commendable start to popular work in this area within the medical humanities. Greatly admirable is Cleghorn’s handling of her own autoimmune disease, Lupus, and how she uses her experience to frame her larger inquiry. The inclusion of her story is both relevant and motivational, without being overly personal.

Lastly, Cleghorn is a feminist cultural historian whose biography includes this sentence: ‘Her own pain and other symptoms were dismissed for seven years before she was finally diagnosed’. I applaud this reclaiming of somatic, bodily experience as a form of knowledge, placing it as an epistemological resource alongside academic and writing credentials; a form of knowledge that is still dismissed in medicine and beyond today. It is this subtle combination of the academic, the literary, and the autobiographical that makes Unwell Women such a thoughtful and thorough read.