Film Review by Professor Robert Abrams, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York

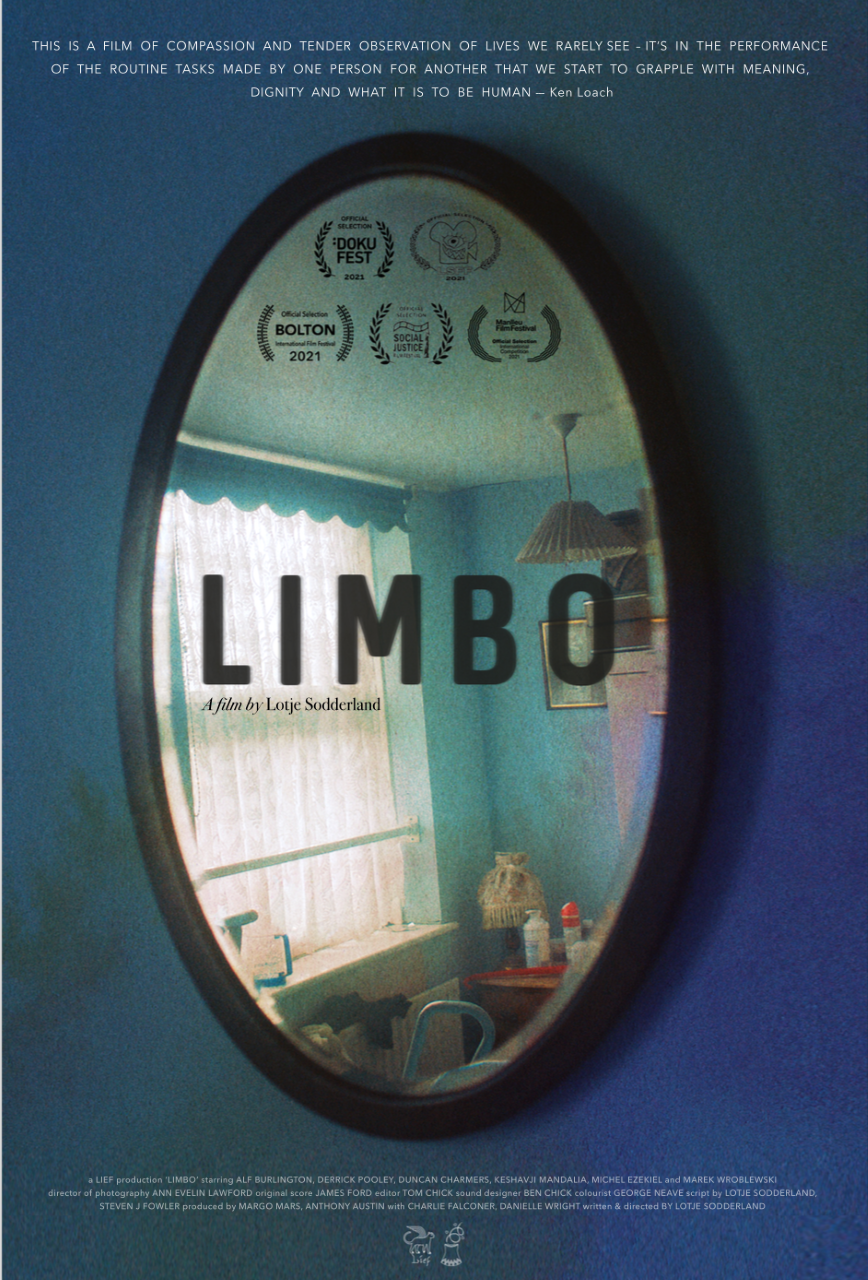

Review of ‘Limbo’ directed by Lotje Sodderland, UK, 2021

Limbo is a short film by Lotje Sodderland, a director best known for the celebrated account of her own hemorrhagic stroke in My Beautiful Broken Brain.[1] Before viewing Limbo, another documentary that portrays real people, not actors, it is helpful to reflect that by choosing this one-word title, the filmmaker is evoking “a forgotten or ignored place.” Limbo is in fact a collective portrait of a forgotten, ignored group of frail old men who live alone and receive supervision from a homecare service. The word “limbo” might also refer to a place of suspension between two other places. In this case, it is between life and death.

The young man at the center of the film is Witold, a Polish immigrant in his 20s who is an employee of a carer agency in London. Witold goes about his daily rounds checking on his charges, assuring their safety, providing hands-on care, and organizing their meals and medications. But he is stressed to his limits by profit-driven employers who text him constantly with urgent reminders to adhere to a punishing schedule. He is never allotted sufficient time to forge relationships with his charges as fully as he would wish, but he manages to soldier on nevertheless. However, just at the moment when he is about to engage in a substantive exchange with one of his clients, his beeper goes off, and he is compelled to rush off to his next appointment.

The principal aim of Limbo’s director was presumably to make viewers aware of the existence of these isolated old men who are largely hidden away from the rest of society (Figure 1). These are persons considered by many to be “throwaways,” no longer productive and now awaiting only death. To Witold’s noisy boisterous roommates, his job is an eccentric aberration, worthy only of derision.

But whether intended or not, Limbo is more than a call for social action and awareness. It addresses an equally important but deeper, subtler question, namely: What makes caregiving work? Leaving aside the commercialization of care for the elderly, what are the human elements, the measures of sensitivity, tact and concern that are required for proper palliative caring? In this film, despite the adverse conditions of his employment, we are privileged to observe Witold as he provides the empathic presence that is the single most essential component of caregiving.

Witold’s work is exhausting, dispiriting at times and poorly paid. Lacking privacy and a place where he can get adequate sleep, he laments that “I can’t even afford my own room”—all conditions that reflect how personal care for this population is undervalued by the larger society. Witold himself is burdened not only by the insurmountable pressures of his job, but also by his commiseration for his clients and the responsibility he feels for their welfare. All told, he is in a state of moral distress.

At one point Witold says: “I don’t even know why I do this job sometimes.” But a short time later he answers his own question: “In our shared shame we find a connection” (Figure 2). The men are shamed by their deterioration, dependent helplessness, and sadness, and Witold is shamed by his awareness of how little he can offer them. But the identifications may in fact be more fundamental than shame. Witold is able to see that generational and age differences are less determinative than the shared humanity that brings people together. As a newcomer not always confident in a second language and whose knowledge of English cultural references is imperfect, Witold is himself a kind of outsider. Perhaps that position helps him to recognize that, de facto, he has now become the most important person in the world to these men.

So he does his valiant best. Witold is quiet, respectful and undemonstrative in manner, but the depth of his feeling is revealed when, after his bicycle has been stolen, he is compelled to race on foot from visit to visit, panicked that he might not reach the pharmacy before it closes or else have to leave each person after an even shorter interval than usual. He is anguished by the medication error he has made in haste. That the lives in his care are soon to end only emphasizes their importance.

Witold eventually comes to realize that his work has personal meaning for him and brings its own satisfaction and rewards. The older men are forgiving of his lapses and the limited time he can give them, and they appear to sense the authenticity of his interest when he asks questions about their past, their work, their loves or the identities of the people in their photos. In so doing, Witold is reaching out to them as individuals, not as generic entities indistinguishable from one another, and he poses questions because he actually wants to know the answers. His inquiries themselves are unremarkable, but they are genuine.

Moreover, within the limits of a short film, we are able to see how relationships evolve. Witold’s exchanges with the men, while of necessity brief, take on greater meaning and warmth. For example, one man, the second of the group, appears taciturn, skeptical and dismissive during his initial visit with Witold. But in a subsequent encounter he is more open, even smiling. Witold himself is now relaxed, not quite as laconic as before and able to joke with him: “They [the pills] go in your mouth and not on the floor.” But because Limbo was filmed just before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, during the first year of which many in-person visits were curtailed, the viewer is constantly mindful of the fragility and transience of the lifelines being offered to these vulnerable persons.

It is in an early scene of the film that Witold’s roommates laughingly taunt him for “groping old men,” referring to the physical intimacy with clients that his work dictates. But the film comes full circle, when in its closing frames Witold brings a white-bearded old man into the bathroom to “sort out” the problems with his urinary catheter. He distracts the man, attempting to ease his anxiety by asking about the Salvation Army, where the man’s son works. With a determined motion Witold then closes the door for privacy against the omnipresent camera (Figure 3). In this moment, the benevolence and respect shown by Witold elevate what might have been a degrading experience to a memorable gesture of compassionate care. The Salvation Army, it is explained, is a kind of church. What is not said but seems to linger on as an unavoidable coda, is that the Salvation Army’s captain might as well be Witold himself.

References

[1] My Beautiful Broken Brain, directed by Lotje Sodderland and Sophie Robinson (United Kingdom, 2014), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Beautiful_Broken_Brain