Blog by Allison Coffelt

I’m sitting by my aunt, who drove two hours after work to see me while I’m in town. She comes straight from the office, and Saturday she’ll get up early to bale hay. At family dinner I ask, assuming yes: she’s vaccinated? Her laugh drops.

“I decided not to.”

The table turns quiet. Of the seven here, she is the only one without the shot. Two in our family are “front line” workers. Two had COVID-19. One was treated for cancer mid-pandemic.

“Can I ask why not?”

“I figured…figured my immune system was already pretty good. Why mess with it?” Anyway, she says, it’s not like, she gestures to her brother-in-law—the one in remission—and he nods. He needs it, she says, and we all agree. I tell her if she has questions, let me know. I have made her uncomfortable, a cardinal sin in the Midwest. The conversation moves on and never returns.

Pre-pandemic, I had not heard the term, “vaccine hesitancy.” I knew of anti-vaxxer parents who lead to measles outbreaks. I knew too often, white, affluent parents’ vaccine rejection impacted children who faced barriers to care like access and continuity—and who were often BIPOC. I knew I could barely discuss vaccines without name-calling. Pre-pandemic, I did not see my dismissive rage as I do now: a luxury I can no longer afford.

Where I am from and where I now live, COVID-19 vaccine rates hang below the national average. Missouri and Utah’s fully vaccinated rates are 40 and 44 percent, while the national average hovers around 48 percent. With fewer than half of my state’s population vaccinated, I wonder about the efficacy of my anger. Will being furious and dismissive get us where we need to be? I doubt it. What we need is better communication—better stories, better metaphors, better tactics to fight disinformation. We need rhetoricians and marketers and personal conversations with our loved ones and neighbors. We need to understand this debate is not new. Many of these fears, given the racial and class history of vaccination, are well-founded. To be effective, public health messaging must address the immortal boogeyman of fear: fear of invasion, death, impurity, and a foreign other. And we assuage fear not with fact, but with feeling.

The first vaccine in the US brought a spectrum of hesitancy.[1] In Boston in 1716, a man named Onesimus, who was enslaved, told Reverend Cotton Mather, who enslaved him, about a treatment for small pox that had been effective in present-day Ghana.[2] Mather wrote the Royal Society with this discovery, partly to record that his understanding came before he learned of the Turkish vaccination methods in Western Europe.[3] A debate began over whether Bostonians should use the vaccination method. Put another way: the earliest form of vaccine was brought to the US before it was the US by an enslaved person and recorded by a slave owner who wanted to establish a name for himself. How might our messaging shift, knowing this history? Like the method from Turkey, this vaccination involved introducing a small amount of the disease into the body. Was it safe? Was it ethical for doctors to introduce foreign material into a healthy person? Was there another way to prevent the disease? These questions are as just as relevant today. “I figured my immune system was already pretty good,” my aunt had said. In other words, No, you cannot introduce a foreign body into me.

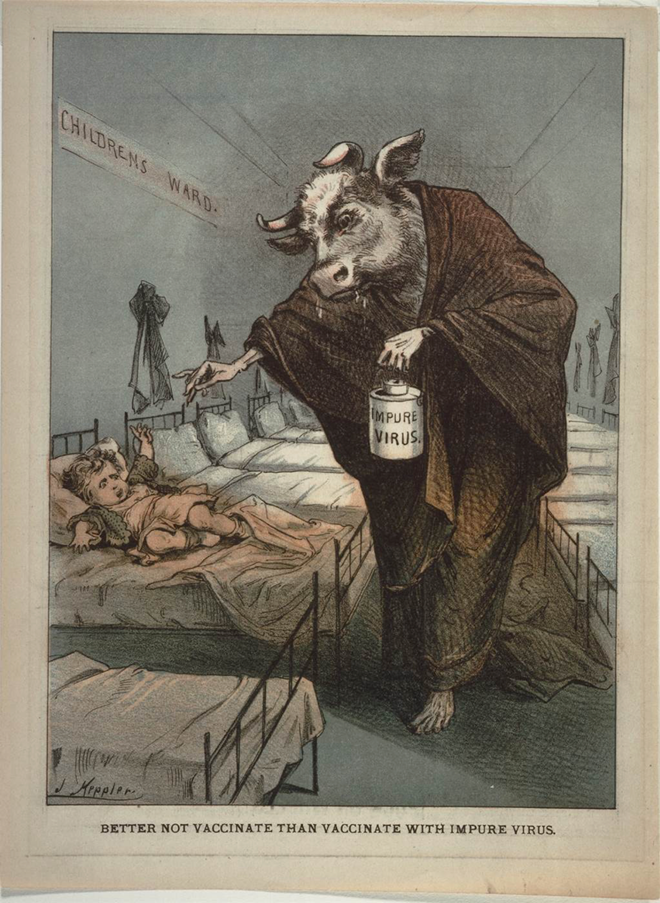

All it takes is a look at this flyer from 1880[4] to see resonances between vaccine fears then and now. In this image, we see vaccines rendered as something thoroughly nonhuman—an alien, invasive creature. Draped in the robe of a grim reaper, the figure’s outstretched skeletal hand and bovine head suggest a chimera: a mix mirrored in the very name vaccina. A small dose of cowpox was used to inoculate against small pox, thus vacca, Latin for cow. This vaccine, the image signals, will rob your child of not only their purity, but their life. The beds extend behind the creature to create what western art calls “the vanishing point.” Above the vacant, light-filled cots, figures of angels are sketched upon the walls, having escorted, one assumes, the children in the ward to eternal life. This is the vividness and severity of fear with which public health messaging must contend. No amount of data will drive away these fears—we need story.

In 1905, when the smallpox vaccine debate made its way to the US Supreme Court, the justices ruled a city or town could in fact mandate vaccination. In question was Boston’s law: residents get vaccinated or pay a five-dollar fine. The evergreen argument of individual liberty versus collective good was addressed in the Court’s opinion: “The defendant insists that his liberty is invaded…” wrote Justice Harlan in Jacobson v. Massachusetts. “But the liberty secured by the constitution of the United States … does not import an absolute right in each person to be, at all times and in all circumstances, wholly freed from restraint,” he continues. “There are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good.”[5] The “common good,” the Court decided, meant a vaccinated public. Less than two decades later, the Court extended the principle to include public schools. School districts, the ruling said, could require students to be vaccinated to attend.[6] Public policy, as we saw with mask mandates and as see with school dictates, has always been crucial to stopping the spread.

To pull one thread in the conversation around vaccination is to unravel personal, political, cultural, and geographic values. To talk of vaccination is to talk of race, justice, equity, liberty, and knowledge-making. Hesitancy is a complex tapestry; we need multiple angles. A successful campaign will be both personal and public. It will be sensitive to narrative and history. It will require a recognition that data will not dismantle fear. A month after family dinner, I call my aunt. Her county is part of the country’s new epicenter. We talk about the weather before I bring up the reason for my call. “I’m worried,” I say. And it’s true. I ask her again about the vaccine and I listen, stopping myself each time I want to interrupt. She shares. At one point, she asks what I think. I take her biggest concern—fear of introducing a foreign body—and I weave a new metaphor. “It’s not like you’re making your immune system weaker,” I say. “At least not in the long run. It’s like you’re showing it a ‘Most Wanted’ sign. “You’re teaching your body to recognize it.”

Works Cited

[1] Dubé, E., Laberge, C., Guay, M., Bramadat, P., Roy, R., Bettinger, J. (2013, August). Vaccine Hesitancy: An Overview. Human vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1763–1773.

[2] Minardi, Margot. (2004, January). The Boston Inoculation Controversy of 1721-1722: An Incident in the History of Race. The William and Mary Quarterly, 61(1), 47-76.

[3] Minardi, 2004, p. 47.

[4] Keppler, Joseph, 1880. ‘The Picture of Health: Images of Medicine and Pharmacy from the William H. Helfand Collection’ (1991), p. 90. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Used with permission; licensing details below.

[5] Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 70, 1905.

[6] Zucht v. King, 1922.

Image: Keppler, Joseph. (1880). Better Not Vaccinate than Vaccinate with the Impure Virus. [Ephemera]. Popular Medicine in America, 1800-1900, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1988-102-109. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough. http://www.popularmedicine.amdigital.co.uk.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/Documents/Details/1988-102-109.

Allison Coffelt is an award-winning author and teacher working at the intersection of health & humanities. Her writing and audio production has been featured in the Journal of the American Medical Association, NPR’s KBIA-FM, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She is the author of Maps Are Lines We Draw: A Road Trip through Haiti, a lyric nonfiction exploration of health equity, colonialism, and the complicated relationship between “here” and “there.”