Podcast with Arabella Proffer

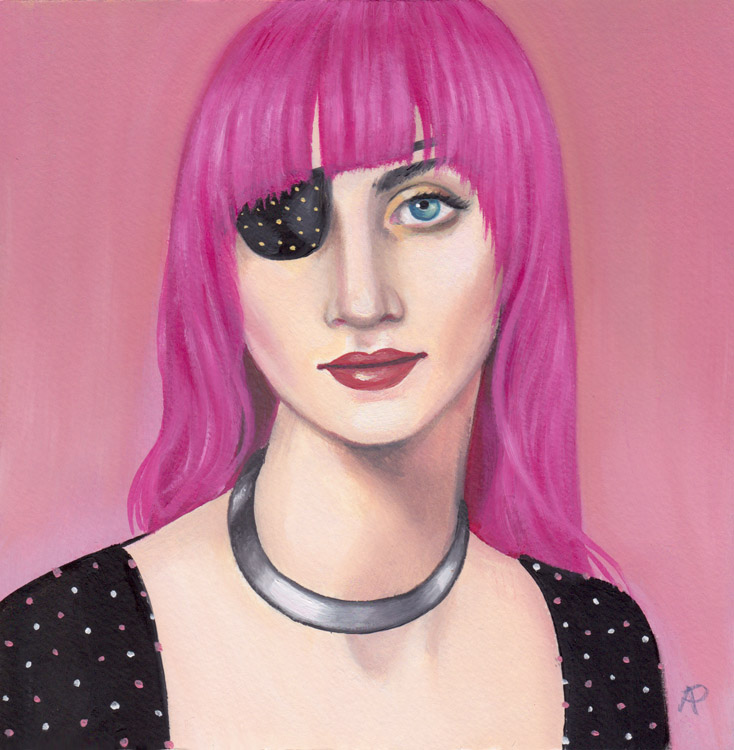

It is will pleasure that I introduce this latest podcast, a conversation between myself and my long-time friend, Arabella Proffer. She is an artist, author, and co-founder of the indie label Elephant Stone Records. Her work combines interests in portraiture, visionary art, the history of medicine, and biomorphic abstraction. Arabella is a force of nature, a brilliant and creative intellect. And Arabella has cancer. Having beaten it once, she took her second chance and traveled widely: she has seen pyramids, shopped in the street markets of Marrakech, ridden camels, seen Florence and the Vatican. She taught me that this one precious life is not something to waste in waiting for ‘right moments.’ Her art, her writing (She has authored several art books including, The National Portrait Gallery of Kessa: The Art of Arabella Proffer (2011) Gurls (2016-17) and The Restrooms of Cleveland (2019) and her life all speak to the spirit of living a whole life—one of color and radiance, and one that is deeply immersed in history, science, medicine. I have always said life at the intersections it more interesting. Arabella is more than a testament to that idea, she is almost its prophet.

It is will pleasure that I introduce this latest podcast, a conversation between myself and my long-time friend, Arabella Proffer. She is an artist, author, and co-founder of the indie label Elephant Stone Records. Her work combines interests in portraiture, visionary art, the history of medicine, and biomorphic abstraction. Arabella is a force of nature, a brilliant and creative intellect. And Arabella has cancer. Having beaten it once, she took her second chance and traveled widely: she has seen pyramids, shopped in the street markets of Marrakech, ridden camels, seen Florence and the Vatican. She taught me that this one precious life is not something to waste in waiting for ‘right moments.’ Her art, her writing (She has authored several art books including, The National Portrait Gallery of Kessa: The Art of Arabella Proffer (2011) Gurls (2016-17) and The Restrooms of Cleveland (2019) and her life all speak to the spirit of living a whole life—one of color and radiance, and one that is deeply immersed in history, science, medicine. I have always said life at the intersections it more interesting. Arabella is more than a testament to that idea, she is almost its prophet.

She is also my very dear friend.

Arabella’s cancer returned in 2020, mid-pandemic. She kindly agreed to join me for this podcast, to talk about life, art, medicine and humanities, and about how to live…when you know life won’t last forever.

LISTEN NOW: Life, Art, Cancer: Living to the Fullest

(Transcript below bionotes)

ARABELLA PROFFER delves into the practice of oil painting tying together its relationships to biology, nature, and emerging sciences. She attended Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA before receiving her BFA from California Institute of the Arts where she studied under artists such as John Mandel, Derek Boshier, Jim Shaw, and Suzan Pitt. Arabella’s work is in over 60 private collections, and she participates in solo and group exhibitions throughout North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Australia. She was awarded an Ohio Arts Council grant in 2016, Akron Soul Train Fellowship in 2019, a Rauschenberg Foundation award, and a Satellite Award from the Andy Warhol Foundation and SPACES in 2020.

Her work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal,The Plain Dealer, The Portland Review, Hi-Fructose, Juxtapoz, The Harvard Gazette, Scene, Snob, SF Weekly, Dallas Arts Review, Pittsburgh City Paper, Westfälische Nachrichten, Hektoen International Medical Journal, Creative Minds in Medicine, and more.

Born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and bred in Southern California, she and her husband live on the shores of Lake Erie in Cleveland, Ohio.

www.arabellaproffer.com

www.artyfartyblog.com

TRANSCRIPT

BRANDY SCHILLACE: Welcome back to the Medical Humanities podcast. I’m Brandy Schillace, and today I’m here with Arabella Proffer. Now, I’ve known Arabella for a long time. She’s an artist. She’s really a polymath in many ways, capable of so many different things. And today she’s here with us to talk a little bit about her life, her work, and her diagnosis and fight with cancer. Arabella, welcome to the show.

ARABELLA PROFFER: Well, thank you for having me.

SCHILLACE: Now, we’ve been friends for so long, and I’ve known so much of what you do. But I wonder, for people who’ve never met you or aren’t familiar with your work, how would you describe yourself as an artist and as a worker?

PROFFER: It’s kind of been changing a lot lately because now I’ve added a photographer into the mix. But I studied animation and film at Cal Arts, and I kind of wanted to do that. Mostly I wanted to be in the film industry, but I’d always been painting. And at Cal Arts, if you were in the Art Department, you got a studio. So, I was like, well, a studio sounds a lot better than a cubicle.

SCHILLACE: [laughs] Right!

PROFFER: So, I stuck with that. And I was doing shows and everything, so I kind of stuck with doing the fine art and being a gallery artist. So, I kind of fell into what is kind of known as the pop surrealist genre, which is sort of, I guess, figurative work, and it falls into the illustration and surrealism. And then, yeah, I just kept on doing with that. And then now I’ve added photographer to the mix of. I did a photography book called The Restrooms of Cleveland, and apparently everyone really dug that, so.

SCHILLACE: I remember. [laughs] It was fantastic! Now, your photography is also kind of an interesting style. It’s not surrealist, I wouldn’t say, but yet it definitely has a very specific— I mean, I can tell that it’s yours, you know. What are your sort of influences for that?

PROFFER: For the photography, I didn’t really have any. [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

PROFFER: I was just more documenting things, I suppose. My only real rule was don’t put the commode in the shot.

BOTH: [chuckle]

PROFFER: So, yeah, that’s interesting you can tell it’s mine, too. ‘Cause yeah, I never use a fancy camera or anything like that. So, it was just more about what can I get in the shot that kind of gives the vibe of the place, you know? [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, mmhmm. Well, it very much tells a story, I think, as your art does too. Some of the earliest pieces that I saw of yours were illustrations of people’s lives. And while they’re fictitious people, they had whole backstories, and they had this really interesting world in which they lived. And that ability of your artwork to tell a story is, I think, really important and valuable, even now that you’ve moved on to things like the more biomorphic art that you do.

PROFFER: Yeah, with the portraits, it was just interesting ‘cause, you know, I would do portraits of made up people. I wasn’t writing biographies for them yet or anything. But at shows, it became clear to me people wanted a story behind it ‘cause they didn’t wanna think of one themselves! They kind of wanted to be told what to think. So, I kind of ran with that, and I started creating stories for these people. And then around 2010 was when I got diagnosed with cancer the first time. And that’s when I came upon the Dittrick Medical, the Dittrick, what’s it called? [unclear; cross-talk]

SCHILLACE: Medical History Center and Museum, I think it’s called.

PROFFER: That’s it, yes. You know what I mean. And that’s kind of like around the time I think I met you. I was stalking you on Twitter, and I didn’t realize you lived in Cleveland.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

PROFFER: And I was like, wait a minute. How come we’re not friends?!

SCHILLACE: Yeah, exactly.

PROFFER: But I—

SCHILLACE: And that, I remember you came to a program that I was running at the museum at the time. For our listeners who don’t know, I used to work at the Dittrick Medical History Museum. And I remember you said that you had actually used some of the medical equipment in some of your paintings.

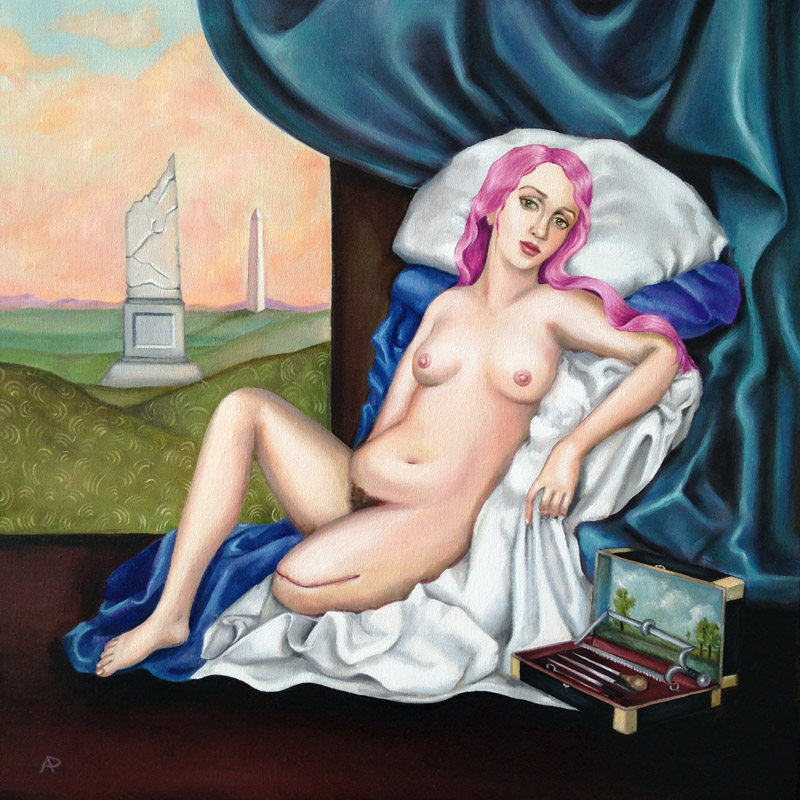

PROFFER: Yeah. So, I started going there for research ‘cause a lot of the portraits I was doing, kind of the time range between like the 1400s and the 1800s, that was the period I was most interested in art history and for fashion and for medical history as well. So, I think, in a way, it was sort of channeling my anger at what had happened to me. And it was a way to feel better about living in this century than in any other century to be treated for anything, especially as a woman. So, that was, yeah, around the time that I met you. And I’d been doing research and incorporating that research into those paintings.

SCHILLACE: Right. And I wanna take a quick minute and kind of talk a little bit about that. Because, of course, when I first met you, you were still recovering. I think you had, you were no longer in radiation therapy. You had recovered, but you were still dealing with the aftermath of that. And I wonder if you could say a little bit more about that. Because I know you and I have spoken about the fact that even our best treatments for cancer today still seem pretty barbaric in many ways. They’re very, very damaging to the body. And so, talk a little bit more about how you handled that. Because I know some of your paintings depict quite gruesome things: amputations, loss of an eye, loss of self. And I wonder if you can say a little bit more about that.

PROFFER: Yeah. So, when I had cancer the first time it is called liposarcoma. It’s 1 percent of like 1 percent of all cancers. It was like a genetic thing where the gene tried to repair itself, and it kind of just did a misfire. So, to treat that, they basically sliced and diced my leg, and I had to walk with a cane for about seven years. And then during my research, I came across a painting of Saints Cosmas and Damian, who are the patron saints of surgery. And it was a painting of someone actually getting the same surgery that I had got for what looked like a sarcoma in the leg. And I was just kind of like, wow. So, this treatment, aside from radiation, really the treatment has been the same all these centuries.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, right.

PROFFER: And my dad died of cancer in 1984. He was actually a guinea pig at NIH. And the treatments that he received then, they’re not that much different now. So, it’s kind of strange what has, you know, advanced like gloves! [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: Right!

PROFFER: You know, gloves. Who would’ve thought?

SCHILLACE: Yes. [laughs]

PROFFER: And gloves are actually kind of a new thing if you look at the history of medicine.

SCHILLACE: Right.

PROFFER: I mean, I can remember being a kid and the dentist having his bare hands in my mouth, you know? So, it was just interesting to me to see what things had advanced and what hadn’t really.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

PROFFER: And I’ve actually talked with my oncologist about this. I said, “You know, in 50 years, they’re gonna look back at this, at chemo and be like, you did what to people? You injected what into them?” And they don’t disagree with me in any respect. It’s kind of like how they treated syphilis with mercury.

SCHILLACE: Right, yes!

PROFFER: It worked, but it kind of didn’t. [laughs]

SCHILLACE: Yeah. It worked by killing you a little bit along the way. And actually, a lot of chemotherapies are essentially attacking the whole system in order to get at one part of it. And of course, the trick is trying to get the system through the attack, you know, what you lose in the process. And it’s funny you mention about design. I think people, when they look at medicine, they so often think about it in terms of strictly STEM. And of course, that’s not true. There’s so much design that goes into the kinds of technologies that we use. And I remember when I worked at the museum, one of the things that surprised me the most is exactly what you’re talking about: not the changes, but the things that stayed the same, you know. The birthing chairs and forceps and things like that, they, for centuries and centuries and centuries, have essentially not changed very much at all. Granted, we get born in much the same way as we always did. So, to a certain degree, you can understand that form follows function. But we do seem to not always think about the fact that it is an artistic endeavor to treat illness.

PROFFER: Yeah. I mean, I remember looking at the X-ray table that was at the museum. And I was like, oh, this looks like the X-ray tables today, except they’re made with more plastic, you know?

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, mmhmm. Now, when you were working on the paintings, you said that, in a way, it was a help processing the anger. And I remember finding the paintings beautiful and yet also incredibly powerful images. They did not seem weak. They seemed strong. And I think that’s something that really comes through in most of the work that you’ve done, including the one that I have that I’ve purchased from you and that is on my wall, is that sense that it’s really giving us this powerful statement about personality. And so, my question for you is, how does that transfer over to some of your more abstract works that you’re working on now, particularly the biomorphic designs? And how has that been part of your journey in all of these ways?

PROFFER: Yeah. So, it was strange. I mean, one day it was before I knew I even had cancer the first time. Like, I felt totally fine. And one day I just didn’t feel like painting people anymore, and I decided to try my hand at doing abstract again. I’d done it before in college, and I was told I should stick with that. But I don’t like people telling me what to do!

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

PROFFER: So, I’m like, no. I’m gonna keep doing figurative work. Meh! But so, I did these paintings. And I sent them down to the Baton Rouge Contemporary Art Center, and they sold immediately. And I was like, oh, this is pretty cool. Maybe I’ll stick with these. And I came from a place of abstraction. There were no advance sketches or anything. So, then I think it was four months later when I got diagnosed, and I was shown the MRIs of everything that was going on in my leg. And it looked exactly like what I had painted down to three tentacles wandering around in my calf and the shape of the tumor and everything. And I was like, wow. OK. That’s kind of creepy. But then I kept with it. [laughs]

SCHILLACE: Yeah, well, actually—

PROFFER: And it was kind of—

SCHILLACE: Just letting our viewers know—

PROFFER: It happened another time too. There—

SCHILLACE: Sorry. Go ahead.

PROFFER: Oh, go ahead.

SCHILLACE: Oh, I was just gonna say letting our viewers—

PROFFER: Oh, I was gonna say—

SCHILLACE: We can edit that. Keep going.

PROFFER: OK. [laughs] There was some photos that were taken during one of my surgeries that the surgeon then emailed to me, and it kind of looked like what I had been painting recently that month. And so, I don’t know if it’s just like a pseudo-psychic knowing of what’s going on in my body or it’s just coincidence. But the biomorphic stuff kind of came from that, was like just this weird knowing and being in touch with what’s going on.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

PROFFER: But at the same time, not having any idea of how severe it is.

SCHILLACE: Right. Right. And I just wanna let our listeners know that we, if you go to the blog post, which will also have a transcript of today’s talk, we will have images of Arabella’s painting so you can see some of the works that we’re talking about. And Arabella, I know you also have a website and several other places people can see your work in galleries and even purchase. So, we’ll make sure to put those links there, too.

Can I ask then, in this latter stage, now we know that you have been diagnosed again with cancer, and this has been something that has been a shock and pretty devastating to all of us who know you. And because you are such a force, you know, such a life force and such an artistic giant in our lives, I wonder how has this affected your ability to work, your desire to work? How do you want to see this in the course of your work as you’re dealing with this new diagnosis?

PROFFER: I haven’t been able to work at all.

SCHILLACE: Really?

PROFFER: So, like, nothing. Nothing. Like it sounds nice, and I would like to. But then it’s just I physically can’t. Mentally can’t. I’m on morphine and oxycodone like 24/7, and that’s just gonna be more and more the case. So, I would like to eventually be able to do that. But I can’t even drive.

SCHILLACE: Mm, mmhmm.

PROFFER: So, it’s just been kind of debilitating. Not only that, but like in a pandemic.

SCHILLACE: Right!

PROFFER: So, I can’t even, you know, go travel or go do things that I would like to wrap up sort of in my life. And I’m just waiting for everyone to stop being a jerk and [laughs] wear masks so I can go do those things.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

PROFFER: But I mean, it’s kind of strange. I was a very morbid child. Like I said, my dad died when I was six. And I used to go to the cemetery all the time and hang out just ‘cause I thought it was a pretty place. And I used to think like, oh, an obelisk. When I die, I want one of those, you know. Or like I want a really cool crypt with Tiffany stained glass. And I used to think about those things all the time.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

PROFFER: So, now I’m in the strange position where I haven’t really been given a timeline, but I sort of have. And so, I had to start making plans, which is strange. I mean, it’s a good thing ‘cause it’s less work for my family and my husband to have to do. But I’m like, wow. It’s like planning your own funeral’s kind of like planning my own last party. It’s kind of weird. And I actually put [laughing] in there that I want an obelisk!

SCHILLACE: I like that.

PROFFER: And I dictated how I want my makeup to look. [laughs] I was very, very specific about a lot of things just ‘cause I’ve been to services of friends where the death was sudden, and you’re like, what would they want? So, I’m really detailed in all my plans and everything. And like when I was a kid too, I remember I asked my mom to make me a funeral dress that I could wear to funerals. [chuckles] And so, now I’m like, OK! Well, what do I wear in my casket? And so, I’m oddly like kind of OK with everything and at peace with it. But it’s, it just sucks for my family and friends though, so.

SCHILLACE: It does suck for your friends. [laughs]

PROFFER: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: [laughing nervously] None of us are dealing with it very well. You know, when we met, partly, you had followed me on Twitter, partly I think, because of the death book. That I had done a book called Death’s Summer Coat about grieving. And I too am fascinated, interested in grief rituals in cultures and in those kinds of plans. You know, what do we want at the end of life? But there is such a big difference between, “I am going to die” and “I’m gonna die soon.” And it changes the way I think, things just suddenly seem really concrete that didn’t used to. And I know mortality is always near, and especially during a COVID pandemic, right, there’s a lot of it about. But to be able to so, with such clear-sightedness, be able to think about not just the event, but even the design of the event, again, is just, you’re always an artist to me, Arabella, I think, whether you’re painting or not.

PROFFER: No, I think I’m just really good at compartmentalizing, maybe. I probably would’ve made a good CIA field agent or something like that.

SCHILLACE: There you go! [chuckles]

PROFFER: But yeah, I just remember, yeah, like, my grandparents were really horrified that my mom had a wake for my dad because they were like very Protestant stock. Like they were from a background where you don’t do that kind of thing. And whereas my mom’s side of the family, there were Irish, so they had those traditions. So, it’s actually interesting how, in America in particular, everyone’s just so scared of it, whereas like every other country, they kind of use it as like you talk about in your book, it’s a way for the community to come together. Or, you know, they would prop up the corpse in the house for like a week, you know, for everyone to come pay respects or. Like you would never have that here. But the closest thing I could find was I did find it is legal in one lake region in Minnesota for you to have a Viking funeral, which it actually sounds—

SCHILLACE: In one region! [chuckles]

PROFFER: -it sounds really interesting. I would actually be into that. But you have to get a permit [chuckling] ahead of time and all that stuff.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

PROFFER: But it’s just, yeah, in America, it’s interesting how terrified everyone is to even talk about it, even when they know it’s gonna happen.

SCHILLACE: Right.

PROFFER: And it’s done in this abstract way, whereas every other culture, it’s kind of in your face.

SCHILLACE: It’s kind of a lot of use euphemisms that are used even around people’s pets and things, you know, rather than an actual open discussion is a lot harder for people, I think. You’re right. At least I found that in the book that I researched: The Western culture doesn’t deal with death particularly well. And the U.S. is, of the Western nations, is particularly bad at it! So, you’re absolutely right.

So, let me ask you, what would you like your legacy to be as we look forward to this future? We have your works. We have things that we can look at and think about. But what do you most want to be remembered for?

PROFFER: I mean, I would most want to be remembered for the paintings and the art. The rest of it, I’m just not sure. I’ve been asked that a few times, and I kind of feel like my legacy isn’t really up to me to dictate.

SCHILLACE: Mm, that’s true.

PROFFER: But yeah, it’s so weird. I was told by my doctors—they tell me after the fact, they’ll never tell me beforehand—but this one was like, “You know, we thought you wouldn’t survive past August.” And then another said, “I thought you’d be gone by September.” So, it’s just kind of thinking even further than like a few days at a time is really hard, so.

SCHILLACE: Right, right. Well, I can tell you that one of the things that has meant the most to me in all of the years that I’ve known you is your absolute grasp of the now and of living, exactly that. That you don’t necessarily focus on a lot of way far away plans. But you’ve been places I never would’ve thought of going. You know, you’ve traveled. You’ve been to Egypt. You’ve been to Morocco. You’ve gone places and done things. What did you used to tell me? “Go to that party. Go to that art opening.” Obviously not during a pandemic, but— [laughs]

PROFFER: No. But once the pandemic’s over. Yeah, I mean, my whole mantra’s been leave the damn house ever since 2010 because, you know, I was stuck in bed for I don’t know how many months against my will. And it’s like, you know, there’s only so much Netflix you can take. And people don’t, I think now they’re starting to realize what it’s like to be cooped up against your will. [laughs]

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

PROFFER: So, but my whole thing was like, even if you’re an introvert, come on. Just leave the house. You never know what’s gonna happen, like fun adventures and what not. And I, yeah, I started traveling a ton because I kind of was taking my own advice, but I was also still sort of looking over my shoulder on the off chance my cancer came back. But as the years went by, that was less and less likely. So, it’s very strange that it would come back almost to the day 10 years later. But yeah, you never know. Leave the house. Go do things. If you get invited somewhere, party, go on a date, whatever it is, go do it. [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: Go do it, and don’t waste your options. Again, this is Arabella Proffer, who is an artist in Cleveland, Ohio, who has done so many interesting things in her life. We’ll have a bio clip of her on the blog that is attendant with this podcast. Arabella, thank you so much for sharing your time with us today. It has been an absolute pleasure to have you on, as it’s always been a pleasure to know you.

PROFFER: Oh, thank you so much.