Blog by Richard Kahn

Yellow Jack, Yellow Plague, Bronze John – these words struck terror in the citizens of a newly formed republic. Yellow fever in the 1790s was a “disease of unknown cause, curious almost haphazard spread, short duration, and often a high fatality rate. It died out soon after a frost and did not appear in cool climates or high elevations. Some thought filth caused its spread, that is, it arose in the fetid, reeking decay around docks. Others believed it to be imported, by ships from tropical lands . . . The very mystery increased the sickening fear it created. It brought business to a halt. People fled from it if they could.” (Bean, W. B. “Landmark Perspective: Walter Reed and Yellow Fever.” JAMA 250, no. 5 (Aug 5, 1983): 659–62.) From 1790 to 1800, most port cities from Boston south were invaded by yellow fever almost every summer. Indeed in 1793, 20,000 of Philadelphia’s 50,000 citizens fled, and of those who remained, 5,000 died.

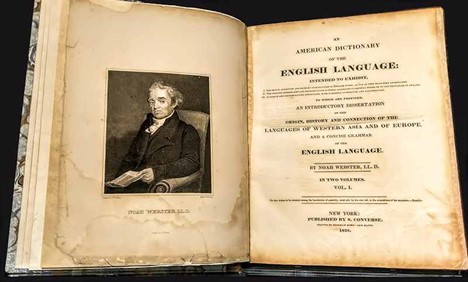

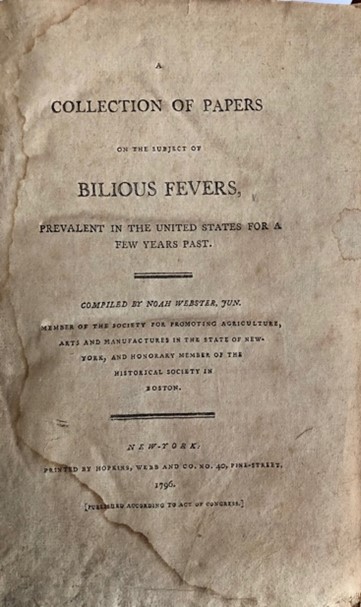

Noah Webster, of dictionary fame, was also interested in science and medicine. Like economists today who recognize our economy will never rebound until the coronavirus has been controlled, he believed that the young nation could not succeed if yellow fever were allowed to shut down the ports each summer, and he decided to do something about it. Knowing the illness could never be eradicated until its origins and spread were fully understood, in October 1795 he published a circular in newspapers from Connecticut to South Carolina requesting information on bilious (or yellow) fever, in particular seeking to find whether it was of foreign and domestic origin.

Webster published the responses to this circular in 1796 as A Collection of Papers on the Subject of Bilious Fevers, prevalent in the United States for a few years past. Webster was convinced that yellow fever was of local origin, caused by conditions such as filth and overcrowding, and was not imported, or “contagious.” And as such, he believed the conditions giving rise to this scourge could be controlled and eliminated, thus providing the philosophical underpinnings for the emergence of public health urban planning initiatives.

Not all his respondents agreed, and in fact of the nine papers presented, five were clearly anti-contagionist, two contagionist, and two were difficult to categorize. New York physicians Elihu Hubbard Smith and Valentine Seaman supported his view, and he used their essays in his preface and summary to strengthen his arguments for improved city planning and sanitation. Valentine Seaman, for example, wrote that yellow fever was more fatal in the “indigent part of the community” due to crowding, difficulty getting nurses, and their inability “to quit their place of residence when the disease came around them.” (Webster, Collection of Papers on Bilious Fevers, 6) On the other hand, Elijah Monson of Connecticut wrote, “I am fully of the opinion that the Yellow Fever is seldom, or never, generated in this country, and that it is always imported from abroad.” ( Webster, Collection of Papers on Bilious Fevers, 182) Today, of course, we know that yellow fever is spread by the mosquito, and is thus both “local” and “imported.”

Asked to continue this important work in 1796, Webster declined, being unconvinced it was worth his time. However, he had seeded an important idea that led directly to the start of the first medical journal in the United States, the Medical Repository. In August 1796, Elihu Hubbard Smith wrote in his diary: “. . .I think, as Mr. Webster has relinquished his plan of continuing his collection, of taking it up myself . . . & publishing an annual volume; the principal object of which will be the preserving & collecting of the materials for a History of the Diseases of America, as they appear in the several seasons . . .” (J. E. Cronin, The Diary of Elihu Hubbard Smith (1771-1798) (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1973), 201.) Thus Smith was a founder and one of the original triumvirate of physician/editors, along with Samuel Latham Mitchill and Edward Miller, when the first issue of the Medical Repository came off the press in July 1797. It continued to be published as a quarterly medical journal until 1824. Ironically, Smith himself died of yellow fever on September 21, 1798, but he and Noah Webster had played a critical role in the development of medicine as science and the emergence of public health policy in the new nation.

Some the above information is found in Chapter 2, Obtaining and Sharing Medical Literature, 1780–1820 of the Introduction to Kahn, Richard J. Diseases in the District of Maine 1772 to 1820: The Unpublished Work of Jeremiah Barker, a Rural Physician in New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Richard Kahn (1940–) is an internist and medical historian who graduated from Rutgers University and Tufts University School of Medicine where his interest in medical history began. He is active in the AAHM and AOS having received the AOS Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.

Works Cited

Cassedy, James H. “The Flourishing and Character of Early American Journalism, 1797-1860.” J Hist Med and Allied Sci 38 (1983): 135-50.

Coleman, William. Yellow Fever in the North: The Methods of Early Epidemiology. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

Cronin, J. E. The Diary of Elihu Hubbard Smith (1771-1798). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1973.

Kahn, R. J., and P.G. Kahn. “The Medical Repository—the First U. S. Medical Journal (1797–1824).” New Engl J Med 337 (1997): 1926–30.

Seaman, Valentine. “An Inquiry into the Cause of the Prevalence of the Yellow Fever in New-York.” Medical Repository 1, no. 3 (1798): 315-32.

Webster, Noah. A Collection of Papers on the Subject of Bilious Fevers Prevalent in the United States for a Few Years Past. New York: Hopkins, Webb & Co., 1796.

Winslow, C. E. A. “The Epidemiology of Noah Webster.” Trans. of the Conn. Acad. of Arts and Sciences 32 (1934): 21-109.