Blog by Audrey Ruan

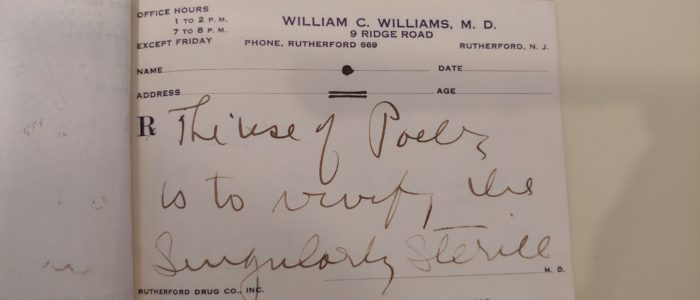

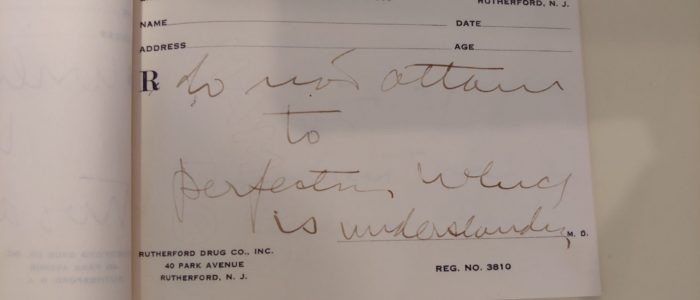

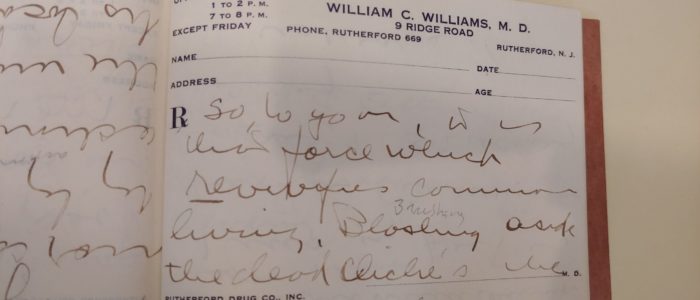

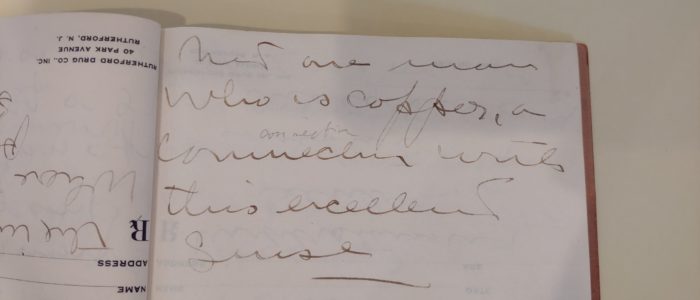

“The use of poetry is to vivify,” William Carlos Williams jotted onto a prescription pad over half a century ago. In the pages that followed, he hastily sketched out a theory of the interwoven contributions of science and poetry, published here for the first time. The prescription book is part of the William Carlos Williams Collection, housed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which the library generously allowed me to study in early March, 2020.

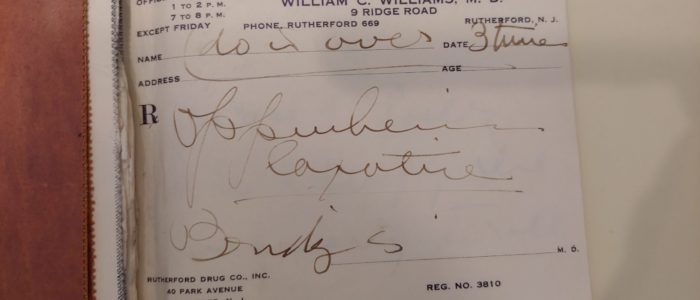

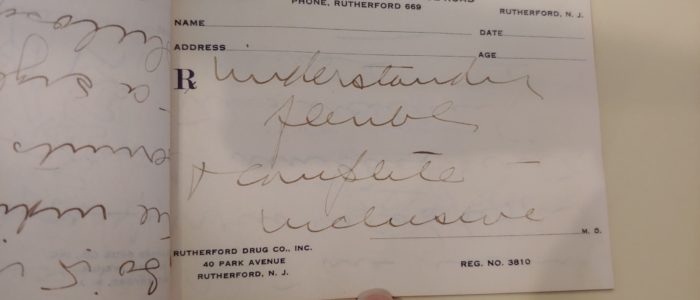

The prescription pad is an unassuming, timeworn booklet. Each page consists of a prescription blank formatted with Williams’ hours of operation, contact information, and space to articulate medical instructions—or wax poetic. Over half of the blanks have been torn out. The remaining pages broadly epitomize Williams’ professions: medicine and poetry.

The first page prescribes a laxative, which Williams presumably neglected to hand to a constipated patient, but the second page launches into an exploration of the effects of poetry on human vitality.

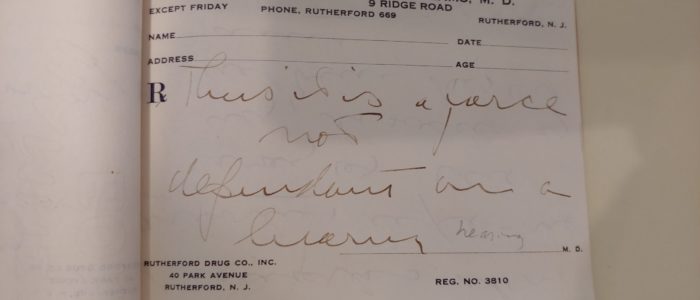

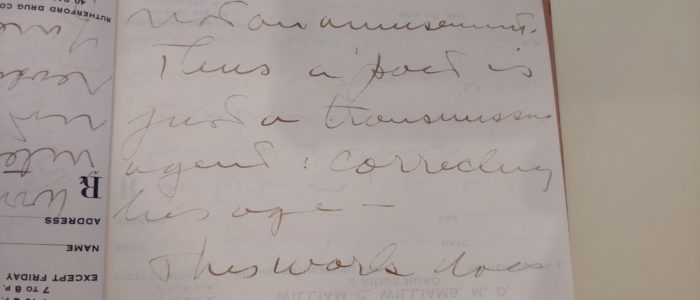

The artifact itself—a booklet of legally-sanctioned forms for medical directives, repurposed to theorize about poetry—instantiates Williams’ premise: poetry is not an “amusement.” It is a “force” that “corrects” the sterility of medicine.

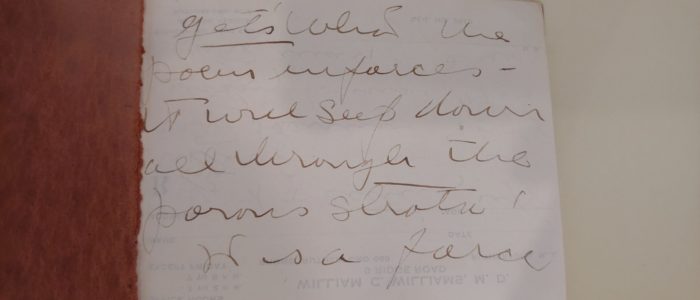

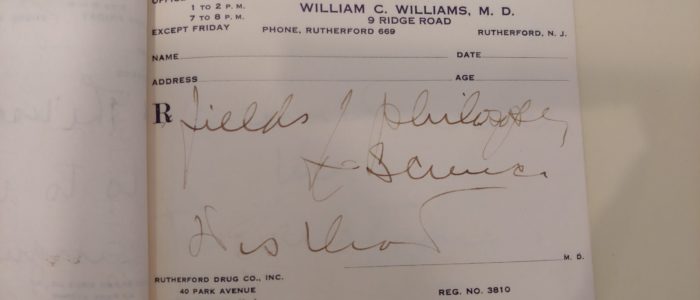

The prescription pad also provides a glimpse of the diurnal interplay between medical rounds and literary expressivity in Williams, who was both Chief of Pediatrics for almost forty years and one of the founding modernist poets. It captures an echo of Williams, in between house calls, hurriedly flipping past the abandoned directive for laxatives to pour from his pen a stream of poetic philosophy across the last thirteen blanks. Flipping to their empty backsides, his thoughts continue for nine more pages, as if writing a prescription for Oppenheimer’s Laxative stimulated an effluence of Williams’ own creative imagination.

Williams was indubitably a profound literary figure, for his poetry foremost, but also writing prose, translations, poetic theory, and plays. He had expressed that he practiced medicine for the purpose of supporting his writing.1 However, his acquaintances, patients, and, most evidently, the four decades he spent treating to his community of Rutherford, New Jersey testify that neither of his vocations was accessory to the other. This truth is integral to examining the theory inscribed across his prescription blanks.

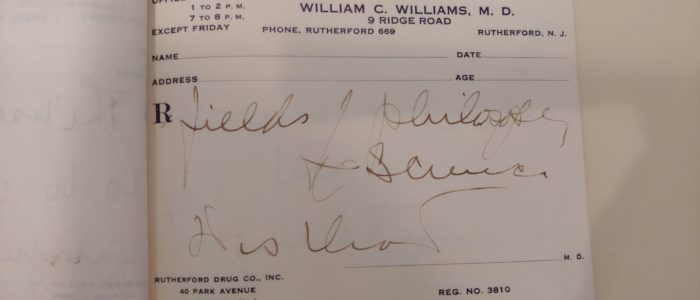

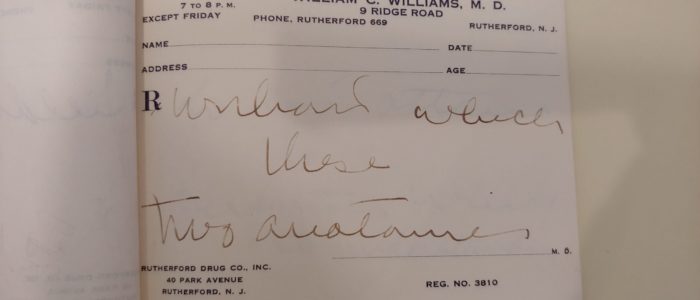

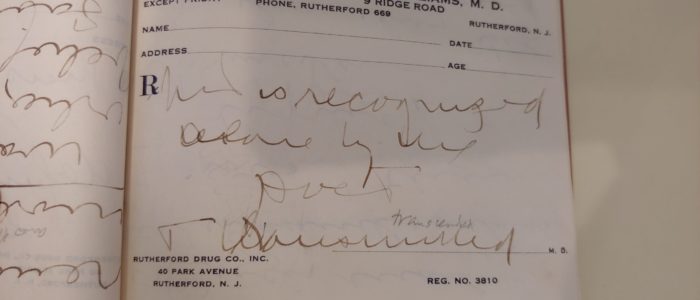

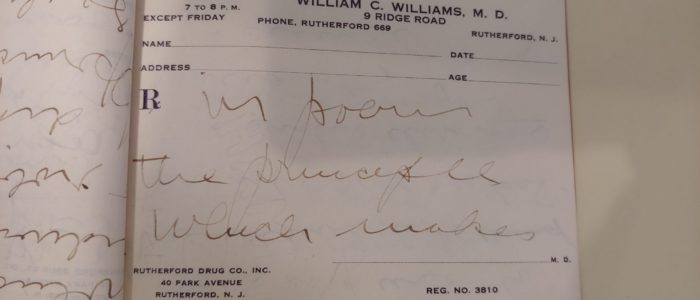

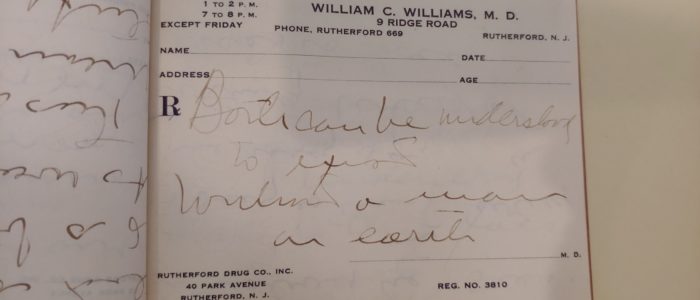

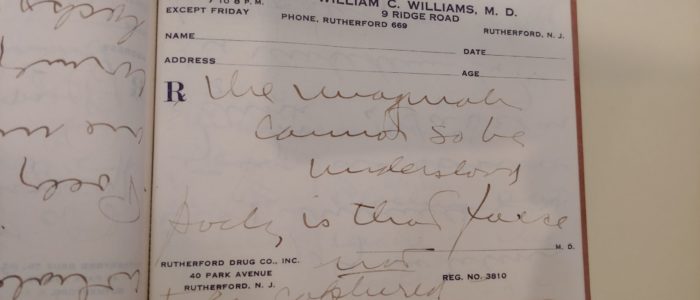

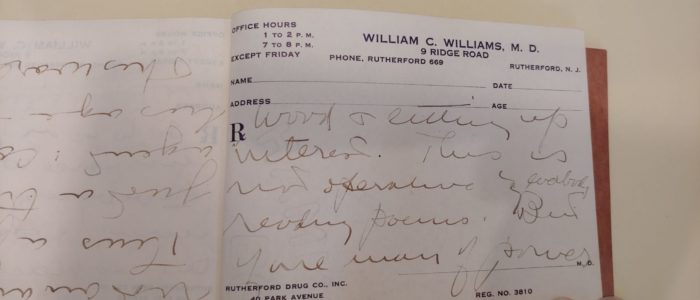

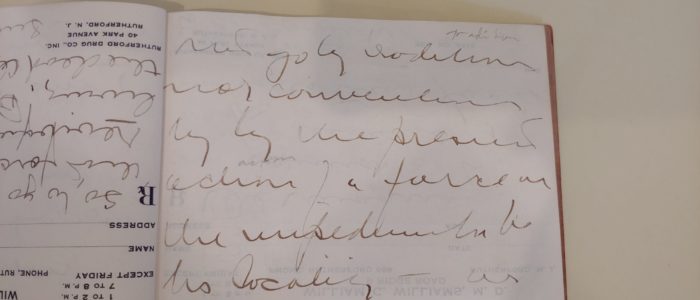

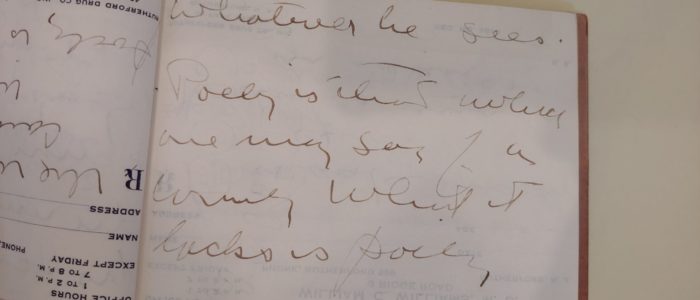

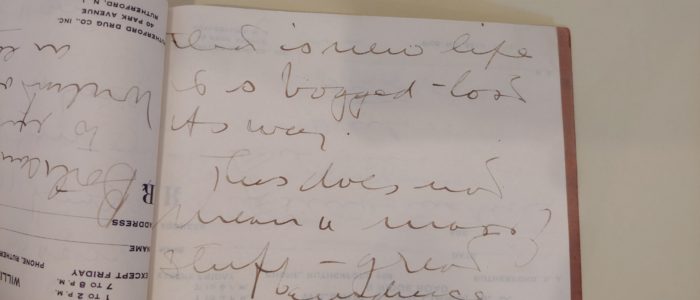

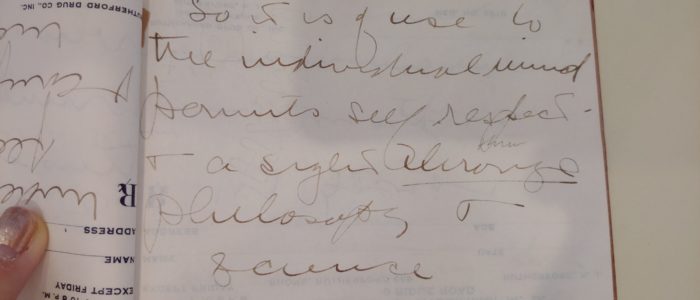

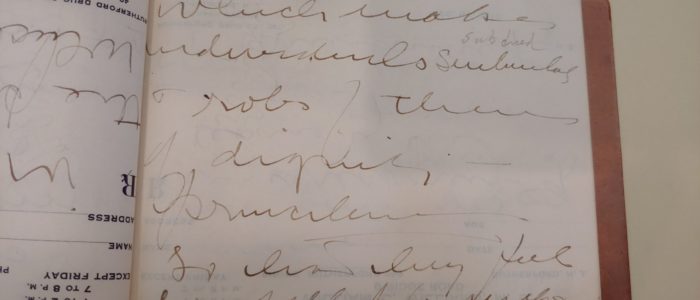

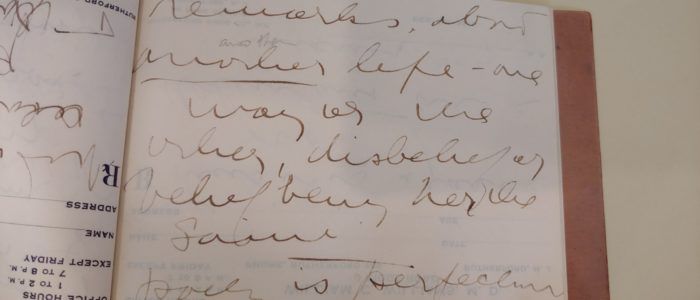

In his draft, Williams exalts poetry. His theory of medical humanities observes that “[poetry] is that force which revivifies common living.” Science and philosophy are established as elements of common living, in a critical light: “[they make] individuals subdued & robs them of dignity.” He notes, emphatically, of poetry: “if all man of power gets what the poem enforces—[it] will seep down all through the porous strata! This is a force, not an amusement.” From these excerpts, we are left with a characterization of science as a sterile, mentally subjugating field and of poetry as vigorous, fluid and rejuvenating.

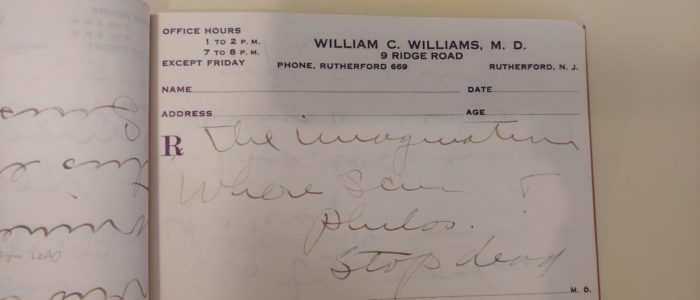

The criticism of “science and philosophy” throughout Williams’ theory gestures toward humanity’s ever-growing dependence on research and reason in problem solving and daily life. This would be especially visible in the medical field, idealized as a source of straightforward health solutions. However, reliance on empirical evidence comes with temporal and technological limits, as well as countless uncertainties. The time required to ethically and validly test and produce research is uncertain. Each patient’s ability to obtain and then respond to treatment, too, is variable. When following guidelines and confronting the unknowns becomes overwhelming, this is “where science & philos. stop dead.”

Prescribing Ambiguity

While medical conventions governing written prescriptions stipulate guidelines to avoid any uncertainty, poetry, of course, intentionally seeks such ambiguities. Williams’ own imagist poetry and his notes emphasize this aspect of poetry: it is imagination, a “force not to be captured” that will heal people, where medicine falls short.

In these paradoxical commitments to science and imagination, Williams draws on his mentor, physician poet John Keats, who first outlined the concept of, and necessity for, negative capability: the capacity to embrace uncertainty. One of the most omnipresent of uncertainties, also prevalent in the medical field, is that of existence: life and death. Where research and rationale leave this puzzle incomplete, imagination fills the void with expression—birthed in the form of the humanities. The poetry of John Keats, the plays of William Shakespeare, the art of Jackson Pollock—they transmit through time so successfully because they bespeak the shared experience of uncertainty in existence. Poetry is communication across the boundaries of time and space. It is the metaphysical medium of the poet, who is “just a transmissive agent.”

Williams’ own life also constitutes this truth. He has explicated, to Dr. Robert Coles and also paraphrased in his autobiography,2 regarding the balance of his two, simultaneous professions: “It’s no strain. In fact, the one [medicine] nourishes the other [writing], even if at times I’ve groaned to the contrary.” In the case of the transcription at hand, Williams’ experiences with medicine fertilized his conclusion that poetry is indispensable to his life, and all lives.

From the moment my research mentor Dr. Sarah Higinbotham and I found Williams’ notes on poetry in the Beinecke Library in the beginning of March 2020, through the months that have passed, the power of poetry in conjunction with science have been impressed upon me in exponentially greater terms. Williams’ opening, “the singularly sterile field… science” has taken on a wholly new light for me as the common living of 2020, too, became singularly sterile. To face a global pandemic, we need vaccine trials, studies, guidance from infectious disease experts… and we also need poetry. The first gives us the highest chances of physical survival and the second allows us to imagine alternatives.

In the midst of hanging onto the news for science, research, and data to present revelations or solutions about Covid-19, I sensed my own calm and creativity evaporating like a spritz of 70% ethanol. I recognized my own need for negative capability and Williams’ theory “seeped” even deeper. Poetry can “revivify” the pandemic statistics. It can articulate and unwind our anxieties. In an age where anxiety prevails and stress kills, what Williams prescribes is poetry.

Notes

1. From William Carlos Williams’ biographical sketch written to U.S. Information Services in 1950, available in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

2. See Dr. Robert Coles’ Introduction to a compilation of William Carlos Williams writings, The Doctor Stories (New Directions Publishing, 1984)