Provocation by Kristin Marie Bivens and Marie Moeller

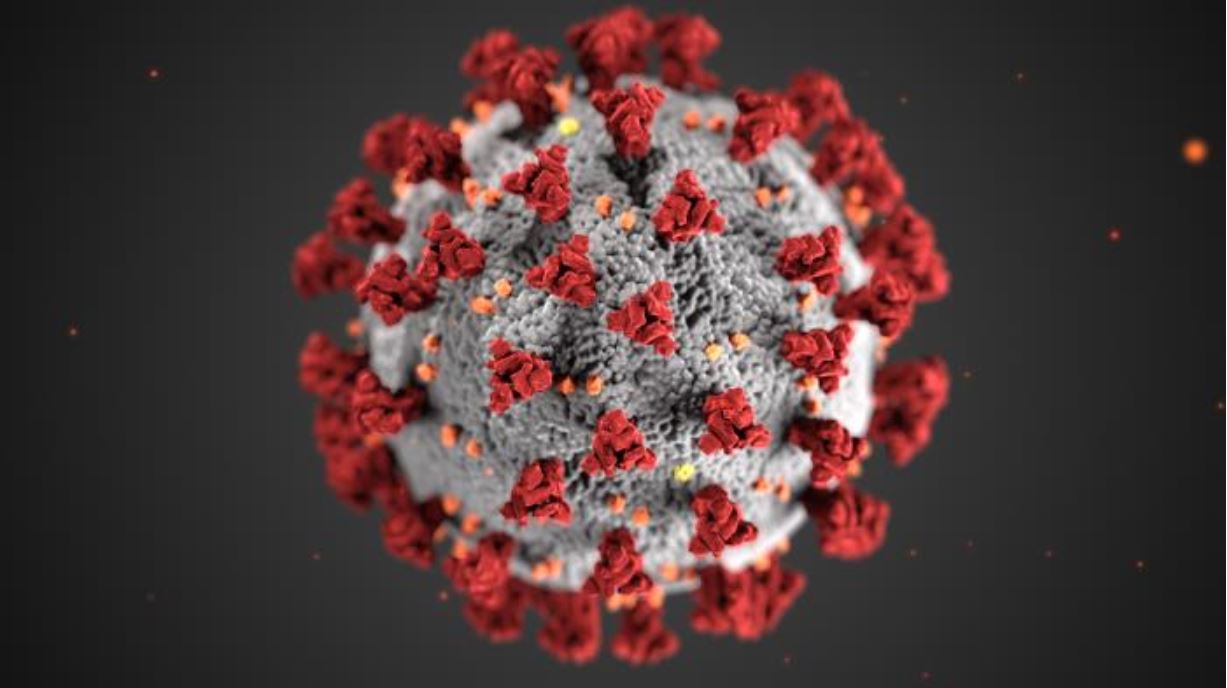

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) medical illustration that represents the novel coronavirus has become the emblem of COVID-19 and the pandemic. In a recent reverse image search, the image returned 5,260,000,000 results in 1.84 seconds. These numbers—over five billion—suggest that the CDC’s image of the novel coronavirus has visually proliferated and regularly accompanied information about COVID-19. In an interview with The New York Times, two medical illustrators—Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins—were awarded responsibility for rendering the CDC’s coronavirus illustration, or the “spiky blob.” Eckert revealed they were tasked with designing “something to grab the public’s attention.” And although it appears the “spiky blob” and its uses have continued to expand internationally, the COVID-19 medical illustration is a scientifically-oriented representation that misses the opportunity to humanize and contextualize the novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

The medical illustration of the “spiky blob,” while scientifically accurate and visually pleasing, avoids conveying the exigency of the current pandemic, the urgency of enacting certain behaviors during this global health crisis, and the human toll it is exacting across the globe. To humanize the virus, we recommend graphic and even grotesque imagery to show how COVID-19 interacts with bodies. We argue that it is in the public’s best interest to humanize COVID-19 and its accompanying visuals. Our contention is that the image does no favors imparting the urgency of COVID-19 health and measures (e.g., washing hands regularly or social distancing). Humanizing the virus and what it does to our bodies might involve making visuals related to the novel coronavirus grotesque and graphic; however, by humanizing the visual and representing the human cost more accurately and grotesquely, it is likely the visuals and the alternative-text will be more powerful, influential, and accessible for the public.

In “Cruel Pies: The Inhumanity of Technical Illustrations,” Sam Dragga and Dan Voss argue that “in certain rhetorical situations—especially in the reporting of human fatalities—conventional illustrations offer inhumanity as though it were objectivity.” In presenting the “spiky blob” as scientifically accurate, yet disconnected from the body, illustrators encourage humans to see COVID-19 as not us, when all signs point to that this “spiky blob” transmits almost solely because of us. We recommend COVID-19 visuals follow Dr. Kathryn Dreger’s humanizing approach from “What You Should Know before You Need a Ventilator.” She explains that while a healthy lung feels like “putting your hands in a bowl of whipped cream,” a COVID-19 lung becomes like a very stale marshmallow. As Dreger reports, one intensive care physician articulates that ventilating a patient with COVID-19 is “like trying to ventilate bricks, not lungs.” These descriptions provide stronger, more humane and accessible imagery of COVID-19 bodies.

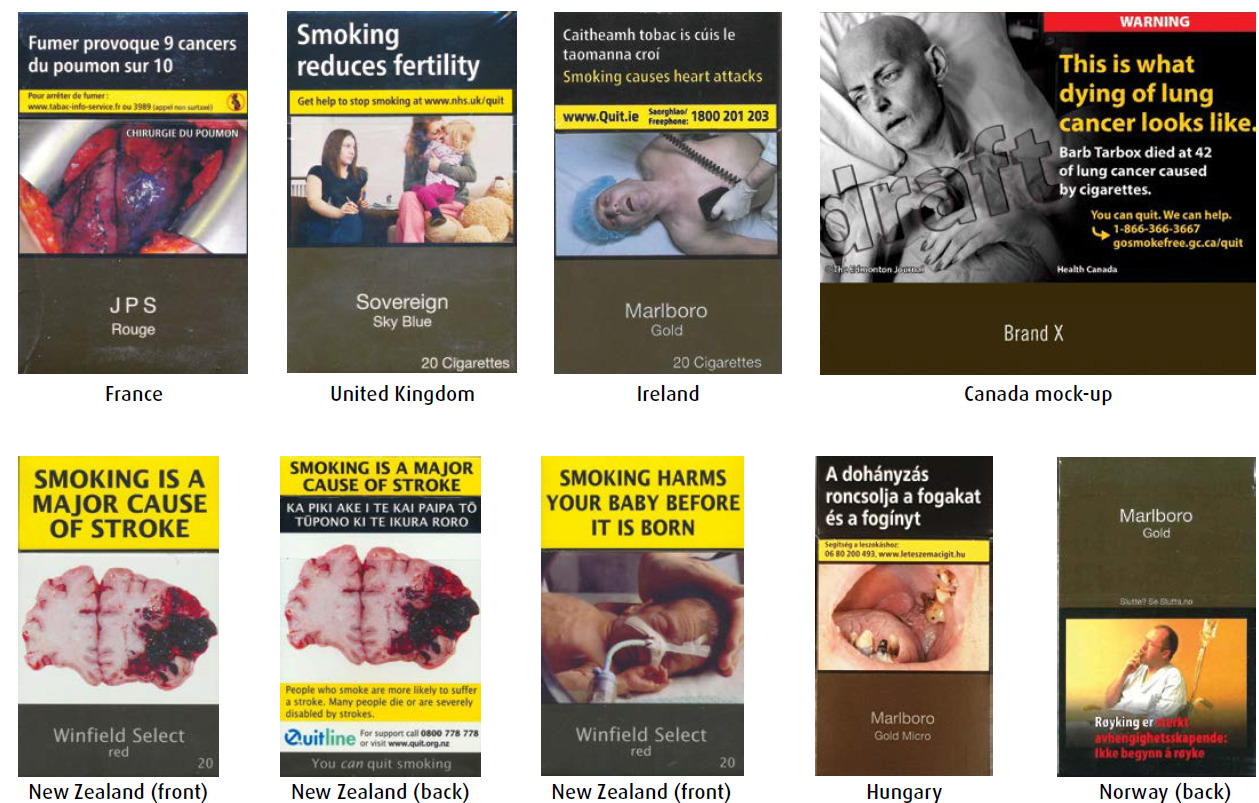

Since COVID-19, its transmission (e.g., spread through oral-fecal contact via flush activated toileted plumes), and its impact on the human body is grotesque, beyond humanizing visuals, we recommend making COVID-19 images graphic and grotesque. Much like the anti-tobacco campaigns in 118 countries that provide graphic warnings to reduce tobacco use on packaging or the CDC’s explicit depiction of Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) on Picture Cards, graphic and grotesque visuals create provocative images that show the potential consequences of tobacco use and unprotected sexual encounters. In both cases, the graphic visuals elicit visceral responses and shape behaviors and actions. For example, visitors to the CDC STD site can see “penile discharge [from] gonorrhea.” The image is accurate, graphic, and explicitly shows those who can see what penile discharge from gonorrhea looks like.

Given the above, in addition to including alternative text for those with visual impairments, we encourage that creators of COVID-19 visuals to:

- Highlight Human Impact: a scientific image of COVID-19 is not particularly persuasive. Grounding images with bodies makes clear that the virus is indiscriminate; such an approach creates community-oriented behaviors.

- Make It Gross: detailed, accurate, and graphic visual representations and descriptions of COVID-19 are more effective for shaping public behaviors. Showing visceral consequences of COVID-19, viewers become more aware of and attuned to COVID-19 bodily realities.

- Include Alternative Text: alternative text for screen readers and those who have visual impairments and disabilities. Alt-text should include detailed descriptions of images, metaphors for content understanding, and contextual information.

Kristin Marie Bivens is a medical rhetorician who studies the circulation of information from expert to non-expert audiences in critical care contexts (e.g., intensive care units, sudden cardiac arrest, and opioid overdose). She is currently working on a monograph manuscript about how sounds shape care in hospital contexts, like neonatal intensive care units.

Marie Moeller is a medical rhetorician studying how documentation from non-profit medical institutions and medical advocacy organizations shapes the lived experiences of the audiences to which it is disseminated. Her work appears in a variety of rhetoric and technical communication journals and collections; she is currently collaborating on a Technical Communication Quarterly special issue regarding the marginalization of bodies in health and medical rhetoric.