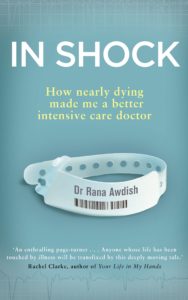

Rana Awdish, In Shock: My Journey from Death to Recovery and the Redemptive Power of Hope (2018), New York: Bantam Press, 272 pp, £14.99.

Reviewed by Róisín King, Trinity College Dublin

Aptly stated by Ed Pellegrino, ‘medicine is the most humane of the sciences, the most scientific of the humanities’. This implies an essential balance between the precision and discipline of science, and the expressive, artistic field of the humanities. When seen too much from one side, medicine loses its intrinsic link between the human and technical aspects of healing. This is why we as medical students and doctors need the arts. No matter how experienced, or how in touch with our feelings we believe we are, our emotionally gruelling career path demands that we take a step back now and then. For our own sanity as doctors, we need an escape; an oasis in the form of a book, a movie, a piece of music or a painting. No matter what our preferred art form is, we must recognise the importance of human expression in our lives.

I have always been an avid reader of both fiction and non-fiction books, and loved them for the unique perspectives they offer one on various issues or aspects of life. However no literature that I have read in the past could have possibly prepared me for the shocking insights that are presented in the memoir of Dr. Rana Awdish. In Shock is a lament for the ancient model of healthcare, where shortcomings in medical technology were filled with a unique healing relationship fostered by doctors with their patients. Although a harsh critic of medical education, this memoir provides a solid foundation for the universal improvement of patient care. This is a book that should be included in the essential reading of every first year medical student’s coursework. There is no physician, student or healthcare professional that could argue that the arts have no place in a healthcare setting after reading this memoir.

Awdish depicts a dark world, where her transition from doctor to patient highlights the ‘dark hole at the center of a flurry of what was otherwise highly proficient, astoundingly skilful care’ (p. 3). At seven months pregnant a sudden onset of excruciating pain hurdles Awdish into the unknown world of patient experience. After losing her daughter, and almost losing her life, she begins to realise the impact of doctors’ language on their patients, and the mental barriers that they construct to protect themselves from their own emotions. Thus begins her determined quest to improve training in emotional intelligence for all healthcare professionals alike. This intensive care doctor’s cautionary tale strives to inform medical professionals on the gaps in training that need urgent filling, and in my opinion she succeeds.

Awdish’s main message to doctors is to see beyond the disease, beyond the ‘seductive…wish for the cure’ (3). Her argument is that rather than physicians centering their care on the patient, the ‘true relationship is forged between the doctor and the disease’ (26). This worrying idea becomes increasingly revealed through Awdish’s patient experience. Young residents prove that they are ‘trained to see pathology… not to see patients’ (26) through hurtful, detached comments and conversations had around her rather than with her. The emphasis is placed always on the disease in medical training, and this detachment is not accidental. Her main aim is to ‘reorient them to the patient beneath all of their entrancing discoveries’ (124). Through Awdish’s eyes I also discovered the shocking gaps in our medical education, about how to deal with emotions, pain and suffering. The efficacy of Awdish’s position as both vulnerable patient and detached observer appeals to a wide audience. We all arrive at our own conclusions with this perceptive woman, that our medical training is not the end of our education.

However, it cannot be said that there is no focus on the more emotive side of medicine in the educative setting. As a first year medical student, I have sat through countless lectures on medical ethics, understanding behaviours and emotions of patients. We sat the HPAT exam in order to gain access to this competitive course, which included an extensive section on emotional intelligence. We are constantly reminded to listen, and to be compassionate in our care. We think that we understand pathologies and patients, but the truth is that ‘vulnerability is not our default state’ (p. 207). We may understand the pathophysiology of diseases, but how can we understand the emotions behind them without having battled a crippling illness ourselves? Awdish’s argument is clear, and it is an urgent call to action for us as prospective and current doctors. No number of lectures or tutorials can teach us to recognise and respond to vulnerability. Learning to engage and to truly heal requires more work than that.

Awdish raises important questions as she engages us in her narrative. The transition from doctor to patient is fraught with difficulties, and as she experiences the gaps in medical education first hand, we begin to realise the importance of ‘a common language’ (255) in the healing of those in our care. Effectively summarised; ‘medicine cannot heal in a vacuum; it requires connection’ (3). Our common language is emotion. Our patients need to connect with their doctors, and we need to connect with our patients and colleagues. Connection is essential for human success, connection with the world around you, with the people around you, and with the arts.

As I read this account I felt the weight of this shared experience. In my opinion this is the beauty of books. They draw you into their world until you can scarcely remember your own. I was with Awdish every step of her journey, and I felt her love, pain and frustration with her beloved profession as she experienced the world from a different perspective. I felt her inspiring hope for a better future for doctors, and for the patients in their care. Through reading her memoir, we can experience what it means to be sick without actually being ill ourselves. Thus we must appreciate the value of doctors like Rana Awdish sharing their terrifying journey from doctor to patient, so we can hope to begin ‘to feel someone’s pain, acknowledge their suffering, hold it in our hands and support them’ (239). We need the arts to teach us lessons that can only be learned through a shared experience. This book has inspired me, as I’m sure it has and will many others, to step into my doctor’s coat with open arms and an open heart.