Emma Barnard MA (RCA)

‘Silence is not Golden’

‘For those who live neither with religious consolations about death nor with a sense of death (or of anything else) as natural, death is the obscene mystery, the ultimate, affront, the thing that cannot be controlled. It can only be denied’.

Susan Sontag

One time, a healthcare professional completely removed the artwork (that I’d made with patients) from the Patients As People exhibition stating that it depicted death. This puzzled me. I couldn’t work out where the offence had come from; the closest reference to death was a thought bubble of the words “RIP” that a patient had drawn over their portrait. That particular patient’s condition was actually relatively minor and not serious; surely the thought bubble merely reflected something we all think about when we are sitting in a hospital waiting room? Where better to contemplate one’s own mortality? GP Dr Jonathon Tomlinson says, ‘Doctors are tortured by the idea that death represents a failure of medicine and this is worsened by a punitive shame and blame culture and highlighted by mortality league tables.’ Medicine has a great deal to offer, and prolonging life is not the only item on the agenda. To paraphrase William Osler, ‘What’s important is not simply what is the matter with the patient but what matters to the patient’.

How do you respond though when someone asks you if they’re going to die?

As artist in residence within an ENT (Head and Neck) clinical department, I have been collaborating with surgeons to explore the patient experience through art. Part of the work I do involves discussing with patients their experiences immediately after the medical consultation, where they reveal what lies behind the mask that they present to the doctor. Very often, patients are at that point trying to come to terms with their diagnoses. On one occasion, when speaking to a patient who had received a diagnosis of laryngeal cancer, to my amazement they seemed unconcerned that treatment might involve removal of their larynx; their major concern was that ‘didn’t want to die’.

As someone whose work as an artist is dependent on being able to communicate both verbally and visually, I am particularly intrigued by a person’s loss of voice and how that might alter his or her life. People not only have to come to terms with having their larynx removed, using a feeding tube and learning to swallow, but they also become voiceless in the conventional sense, having to relearn how to communicate. As laryngeal cancer survivor Kay Baker states, ‘I felt as if my personality had been taken away from me because I could not express myself anymore’.

It is not the words spoken by the voice that are of importance, but what it tells us of the speaker. Its tone comes to be more important than what it tells. “Speak, in order that I may see you,” said Socrates. (1)

(Reik, 1956, p.136)

The voice is one of the most important means by which we communicate. In the words of Alice Lagaay, an academic philosopher from Bremen University:

‘A voice is both individual and communal: On the one hand, every human voice is unique, no two voices are ever quite the same. In this sense every voice is the signature of an individual’. (2)

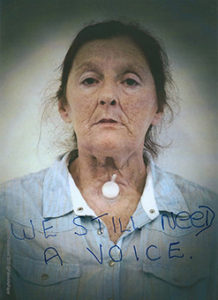

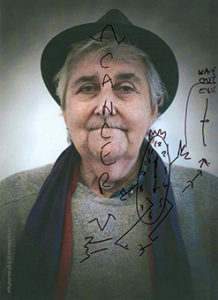

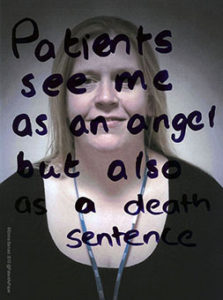

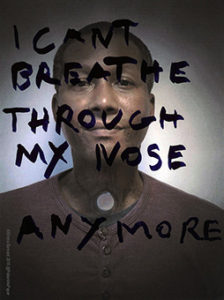

Portrait photographs (which contain their drawings) of people who attend the Talking Heads group held at St Josephs’ Hospice which supports people who have had experience with laryngeal cancer.

The building was warm, friendly and welcoming. But in fairly familiar community-type surroundings, the sounds that I heard were not. I had been invited to present my work on patient experience to the group ‘Talking Heads,’ a support group for people who have dealt with laryngeal cancer; more often than not they are without a regular ‘voice’. Denise Redmond, having worked as a Macmillan nurse for some time facilitating the support group for laryngectomy patients, reflected: ‘If you removed the gearbox in a car then the car would have no useful function and be scrapped. Patients with laryngectomies really humble me in their ability to overcome not only a cancer diagnosis but to survive and live beyond their cancer treatment with a significant impact of treatment. There is always a trade off with cancer treatment especially when the aim is to cure somebody. Removing the organ that lets the patient communicate, speak, sing, breathe and eat and drink which are normal basic functions to sustain life is debilitating holistically. It is a life-changing event’.

‘That’s great, it looks lovely and clear now’, said the surgeon. Physically, everything looked good and how much easier it would be if illness was just about an individual’s physicality. That’s not the case, of course, the mental scars remain, exacerbated by lack of understanding from family, friends, and others, too often scared of the change in you as you speak in a way that they do not understand. Denise: ‘There are many misconceptions about “neck breathers” and they can be very isolated. I know doctors and nurses who are afraid to look after patients that have laryngectomies as they perceive the laryngectomy as difficult and complex when the patients themselves are masters of their own care’.

Mike Papesch FRACS, an ENT Head and Neck consultant surgeon explains his viewpoint: ‘From a surgical point of view, it is very clinical…with the end goal being survival and with recognised significant social, psychological and personal impact. It is impact that may be underestimated by the patient, but it is not underestimated by the medical team looking after them. And indeed, the doctor understands the difficult choices that patients have in undergoing these treatments. Perhaps it is that the patient, in reality, has no choice as to the treatment and its impact, if they do not wish to die of the disease. The reality they face truly is this harsh. And the patient will never fully understand what it means to have head and neck surgery, until after the process. This process can take place over several months. People do make some recovery, but never return to their pre illness performance status. I would not wish this surgery on anyone, but if they needed it, I would embrace it, advise it, and undertake it willingly, knowing full well it was done as a lifesaving, albeit life changing, intervention’.

Illness isn’t something you wave goodbye to in the consultation room after your appointment or in the theatre after a surgical operation. It follows you home, it is with you while you sleep and haunts you in your waking moments. In the words of Susan Sontag ‘Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick’. Days, weeks, years, and it is still there, refusing to let go. Unlike other cancers, which to a certain degree, are invisible, this one remains in full view for all to see and because there seems to be so little knowledge on the after effects, responding to someone who has had this disease can be uncomfortable for the onlooker.

Of the legacy that is laryngeal cancer, two years on Kay Baker writes:

No airway

No smell

Not much taste

Eating and drinking very slow

Have to be very careful in the bath – cannot get water down my stoma

Never go swimming (would drown)

More difficult to breathe especially in very hot, cold and windy weather

My life is so different now and there have been times when I have had bad thoughts – why this cancer, why me? Not wanting to live.

What I don’t like is people thinking there is not a PROBLEM.

No escape – there is a constant reminder every minute of the day – as soon as I wake up, unlike other cancers.

There is no hiding place.

Silence is not GOLDEN as the song goes!

‘Silence remains inescapably a form of speech’. Susan Sontag

References

1 Reik, T. (1946) The Ritual: Psychoanalytic Studies, Bryan, D. (trans). New York: International University Press.

2 Lagaay A 2008 Between Sound and Silence: Voice in the History of Psychoanalysis Freie Universität BerlinVolume 1 (1), ISSN 1756-8226

Emma Barnard MA (RCA)

Bio

Emma Barnard is a visual artist, specialising in lens-based media and sound installations. Her work deals with social commentary, seeking to highlight contemporary issues and encourage debate surrounding them. The experience Emma has gained through several years of working with consultant surgeons and their patients from various disciplines, including ENT and Psychodermatology, is now influencing the field of medical education. Her “Patient as Paper” project (co-founded with Mr Mike Papesch FRACS, ENT consultant surgeon) artwork is currently being exhibited widely in galleries, universities and hospitals in England and internationally. It has been presented at several conferences within the medical and medical humanities fields, and most recently at University College London, Medical School and in a series of presentations at Surrey University for the Department of Health Sciences. At King’s Medical School in London Emma has led a highly successful pilot project to introduce art into medical education, undertaken in conjunction with a critical care consultant and a fourth-year medical student. An exhibition of this work is planned for later this year.

@PatientAsPaper

Exhibitions:

‘Patients As People’ (work created alongside patients) – currently installed within the Department of Health Sciences, Surrey University, Guildford

More information:

https://www.facebook.com/PatientAsPaper/?ref=aymt_homepage_panel

‘A Stitch in Time’ series of works to be shown at The Lawson Practice, London at the invitation of GP Jonathon Tomlinson during February/March.

Artist page – BerlinBlue Art: http://www.berlinblueart.com/emma-barnard