This is the first of a series of comic book reviews on the theme of Dementia. Reviews of Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles and Dana Walrath’s Aliceheimer’s to follow.

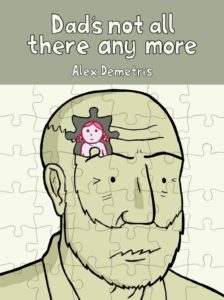

Dad’s Not All There Anymore by Alex Demetris

Reviewed by Harriet Earle

As an academic, I have a love-hate relationship with Wikipedia. I tell my students to steer well clear and never to rely on it for anything but the most cursory glances at a subject. However, I will admit that I use it regularly (and, in the website’s defence, the references can often be very helpful). There is absolutely a place in academia – and in life – for Wikipedia’s accessible and easy synopses. It is likely that, were I to require information on Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), I would soon be typing it into my phone’s app. However, one central thing that is missing from Wikipedia is heart. An encyclopaedia is not meant to be an emotional and emotive document; it’s aim is to inform, not to evoke emotion. However, when one is talking about many topics, such as LBD, the basic definition (or even an exhaustive medical definition) does not give any space to the consideration of the experience of the condition.

This is where Alex Demetris’ comic Dad’s Not All There Anymore comes in. Demetris illustrates his father’s diagnosis and eventual move to a nursing home. Demetris’ book is devastating and heart-warming. He tells the story through the figure of John. When the narrative opens, we are visiting John’s father, Pete, in a nursing home. John speaks gently to two other elderly residents, one of whom is supine on the floor, before meeting his mother, Sue, in his father’s room. The chronology of Pete’s illness is told in flashback; we follow him from diagnosis with Parkinson’s in 2003, to the diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia in 2007 and the progression of the illness until John barely recognises his father. The personal story is interspersed with carefully worded explanations of the condition, its genesis and development that are pitched perfectly for readers who are not medics. This is the true success of this comic – that Demetris is able to create a work in which his father’s unique story and the more generic definitions of LBD sit in conversation with each other. We are in no doubt that this is a personal story and that it is the individual nuanced experience of the disease that is the focus, while the medical information exists within the text as an informative touchstone for the non-medic reader.

Demetris’ artwork is both expressive and simple. Plain line drawings with very little excess details are highlighted by shades of yellow-green. In places, there is a flash of red. When Pete starts to hallucinate a small red-haired child, she lurks as a faded red and creepily expressionless figure; she is almost a ghost. In another instance, Pete asks John what he sees in the corner. John sees a rack of coats; Pete sees the bright, terrifying face of a clown, to the horror of the clown-phobic John. In curious contrast to the muted and gentle colouration, the panels themselves are crowded. Each page contains at least 6 closely-packed panels, each one filled with a bustling image, topped with a caption or bubble or both. There is a lot to take in – both image and text – and at times the effect can be overwhelming. Where to look? What to read first? I would not wish to suggest that that chaos engendered by the reading experience can come close to mimicking the full horror and disorientation of LBD but it may go some way to mimicking the mental upheaval of supporting a family member.

All comics artists have a style and in that style is a peculiar ‘something’ that stands out. For Demetris, it is his exquisite use of eyebrows to create expression. In my own research, I have written about the importance of the eye as a frame to govern the emotion of the face within the panel. Demetris’ characters have no eyes, only small representative dots, and so it is for the eyebrows to do the talking. It is impossible to overstate how expressive Demetris’ characters are, a feat that is particularly impressive, given the limited use of detail in their faces. In the visually congested panels, the clearly rendered eyebrows on each face guide the narrative and emphasise the humanity of the characters, in moments of both comedy and tragedy.

Ask most people to name something that terrifies them and they are likely to rank dementia high on that list. I imagine that watching a loved one battle with dementia is equally terrifying. In the carefully rendered faces of John and Sue, there is immeasurable warmth. Indeed, one of the most striking features of the plot of this comic is the seemingly unwavering devotion of both characters to Pete and their tremendous patience with him as the disease progresses. It is one thing to say of a sick family member “he doesn’t mean to be trying, he’s not well – I will not hold it against him” and quite another to live these words and embody them. Demetris is not telling just any story of LBD, he’s telling his father’s story. The personal nuances of the story are the central focus of the narrative and the most compelling part of it. Pete was a teacher and regularly admonished his son for using the word ‘innit’ (“Don’t say ‘innit’ – it’s bad English”). At the book’s close, there is a final glimpse of the old Pete and his grammar policing ways (“… shouldn’t say ‘innit’… bad English…”). LBD may have him on his knees but he is still there and it is to this that his family cling. This is the heart; this is what moves this text beyond the crisp, cold definitions offered by Wikipedia and other encyclopaediæ. Instead of receiving the bare facts, the reader receives an insight into the day-to-day experience of the disease and the ravages it brings to bear on the individual and those around them. Demetris has etched out a fine line between text book and autobiography and is walking it with skill, panache and immense heart.

Dad’s Not All There Anymore by Alex Demetris is available from Singing Dragon Publishers.

ISBN: 978-1-84905-709-7

Price: £7.99

Related Reading

, Yugin Teo. Carers’ responses to shifting identity in dementia in Iris and Away From Her: cultivating stability or embracing change? Med Humanities 2015;41:2 81–85

Deliver us from evil: carer burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Humanities 2010;36:2 101–107