Hope, Oncology and Death

Seamus O’Mahony

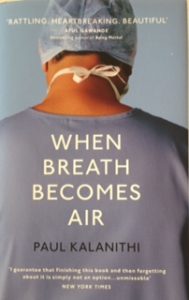

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. London: The Bodely Head, 2016.

Paul Kalanithi was nearing the end of his neurosurgical training at Stanford when aged thirty-six, he was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. He had never smoked. He was referred to an oncologist specializing in lung cancer. “Emma Hayward” – not her real name – is a central figure in his posthumously-published memoir When Breath Become Air. At their first consultation, Emma refused to discuss survival statistics for stage IV lung cancer, but encouraged Kalanithi to return to work as a surgeon. I shared Kalanithi’s initial reaction: “Go back to work? What is she talking about? Is she delusional?” He argues that for the patient, cancer survival statistics are of little help or succour: “It occurred to me that my relationship with statistics changed as soon as I became one . . . Getting too deeply into statistics is like trying to quench a thirst with salty water. The angst of facing mortality has no remedy in probability.”

But statistics and probability were important for Kalanithi. Examining his options, he reasoned: “Tell me three months, I’d spend time with family. Tell me one year, I’d write a book. Give me ten years, I’d get back to treating diseases.” After an initial encouraging response to chemotherapy, his oncologist is wildly optimistic:

Going over the images with me, Emma said, “I don’t know how long you’ve got, but I will say this: the patient I saw just before you today has been on Tarceva for seven years without a problem. You’ve still got a ways to go before we’re that comfortable with your cancer. But looking at you, thinking about ten years is not crazy.”

As it turned out, Kalanithi survived for twenty-two months following his diagnosis, some distance short of ten years. Encouraged by his oncologist’s optimism, as well as Samuel Beckett’s famous exhortation (“I can’t go on. I’ll go on”), he returned to work as a surgeon: “One part of me exulted at the prospect of ten years. Another part wished she’d said, “Going back to being a neurosurgeon is crazy for you – pick something easier.”” Returning to the operating theatre, he had to lie down during his first case, but “over the next couple of weeks, my strength continued to improve, as did my fluency and technique.” Soon, however, the stark reality of his disease caught up with him:

But the truth was, it was joyless. The visceral pleasure I’d once found in operating was gone, replaced by an iron focus on overcoming the nausea, the pain, the fatigue. Coming home each night, I would scarf down a handful of pain pills, then crawl into bed . . .

Inevitably, as his disease progressed, he knew he could no longer work as a surgeon. When a CT scan showed that his disease was advancing again, “Emma Hayward” managed to put a defiant, Churchillian spin on the situation:

“This is not the end,” she said, a line she must have used a thousand times – after all, did I not use similar speeches to my own patients? – to those seeking impossible answers. “Or even the beginning of the end. This is just the end of the beginning.”

And I felt better.

On the day he was due to attend the graduation ceremony from his residency program, Kalanithi was taken suddenly ill, and ended up in the Intensive Care Unit, where various specialists, including nephrologists, endocrinologists, intensivists and gastroenterologists squabbled over his treatment. Kalanithi refers to this as “the WICOS problem” – Who Is the Captain Of the Ship? Emma – who had been away on holiday – returned, and took over the role of captain. Having pulled her patient through this crisis, she reverted to her relentless optimism: “” You have five good years left,” she said.” Kalanithi, however, saw this wishful, magical thinking for what it was: “She pronounced it, but without the authoritative tone of an oracle, without the confidence of a true believer. She said it, instead, like a plea.” He is remarkably forgiving of this fudging and fibbing, this hesitation to be brave:

There we were, doctor and patient, in a relationship that sometimes carries a magisterial air and other times, like now, was no more, and no less, than two people huddled together, as one faces the abyss. Doctors, it turns out, need hope too.

“Emma Hayward”, like many American oncologists, is part conventional cancer doctor, part shaman. She seems to have been able to simultaneously believe two truths. The conventional cancer doctor part of her surely knew that Kalanithi was, at that point in his illness, unlikely to survive five months, let alone five years, yet the shaman part of her half believed the lie she was telling her patient and herself. Her no doubt well-intentioned exaggeration of Kalanithi’s survival prospects led him to take the ill-advised decision to go back to work as a surgeon, when his remaining time might have been more fruitfully spent with his family and his books.

Kalanithi muses on the nature of hope in terminal illness:

When I talked about hope, then, did I really mean “Leave some room for un-founded desire?” No. . . So did I mean “Leave some room for a statistically improbable but still plausible outcome – a survival just above the measured 95 percent confidence interval.” Is that what hope was? Could we divide the curve into existential sections, from “defeated” to “pessimistic” to “realistic” to “hopeful” to “delusional”? Weren’t the numbers just the numbers? Had we all just given in to the “hope” that every patient was above average?

Atul Gawande wrote how the entire edifice of American cancer treatment is based on the assumption that all patients with advanced cancer are in the small, statistically favoured end of the bell-curve, the medical equivalent, he observed, “of handing out lottery tickets.” Cancer patients are routinely treated on this assumption (or hope), but are not prepared for an outcome – death − which is overwhelmingly more likely. Optimists would cite the example of the palaeontologist and writer Stephen Jay Gould, and his famous essay, The Median is not the Message. Diagnosed with a rare form of cancer (primary peritoneal mesothelioma), Gould looked up the survival statistics, and found the median survival was just eight months. He noticed, however, that the survival bell-curve was not symmetrical, that it was right-skewed, with a small minority of long-term survivors. Gould reasoned that he might just be in this small minority: “I possessed every one of the characteristics conferring a probability of longer life: I was young; my disease had been recognized in a relatively early stage; I would receive the nation’s best medical treatment.” He was right: he survived for twenty years, dying of an unrelated cancer. I would imagine that this essay is holy scripture for American oncologists.

I am, I confess, an oncology apostate. Cancer treatment seems to offer some patients a toxic combination of false hopes and a bad death. And the oncology community itself acknowledges this. The Lancet Oncology Commission produced a lengthy report in 2011 called Delivering Affordable Cancer Care in Developed Countries : “The medical profession and the health-care industry have created unrealistic expectations of arrest of disease and death. This set of expectations allows inappropriate application of relatively ineffective therapies . . . cancer treatment is becoming a culture of excess.”

Can we give our patients hope, yet still be honest with them? “Hope” has acquired a very narrow meaning in the cancer setting, namely, an expectation of long-term survival. But for our patients, hope can mean all sorts of things: a reassurance that they will not suffer unbearably, an opportunity to settle affairs and spend time with family, a sure knowledge that their doctor will accompany them on the road as an amicus mortis. Giving hope does not mean creating an atmosphere of histrionic pretence, an atmosphere which inevitably explodes as the end nears. Hope and honesty are not incompatible.

Unfortunately, honesty is heavily disincentivized in modern medicine. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012 found that the less patients with advanced cancer knew about their prognosis, the happier they were with their doctors. Nearly all families, and many patients, prefer the Lie. Although he eventually realized that his oncologist was telling him what she thought he wanted to hear, Paul Kalanithi believed in, and acted on, her initial over-optimistic prognosis. If a man as well-informed and intelligent as Kalanithi could buy the well-intentioned Lie, what hope for the “ordinary” patient?

Seamus O’Mahony’s book The Way We Die Now was published on May 5 by Head of Zeus.