A reflection on Sofie Layton’s Under the Microscope by Giovanni Biglino (Bristol Heart Institute, Bristol, UK)

The voice of a little girl and the sunlight filtering through layers of green batik – a series of coral-like structures representing real heart models displayed under bell jars – anatomical drawings – and the story of a boy’s heart transplant…

With her ambitious piece Under the Microscope, artist Sofie Layton has created two powerful installations, both rich in imagery and charged with people’s voices, during a yearlong residency at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London.

The artwork aims to explore how patients and families process medical information, particularly in the context of rare diseases. Layton’s delicate rendition manages to achieve the aim and to go beyond, in a moving exploration that encapsulates the technicalities of scientific research around rare diseases as well as the strength of young people that are born with these conditions.

The installations focus on two different medical scenarios. In isolation is centered on severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), whilst Making the invisible visible explores congenital heart disease.

The first recreates an isolation tent, made out of fluttering green/yellow batiks on which the artist has printed golden and silver viruses. Inside the tent, there is a bed, and a touching soundscape in which three voices alternate: a young Danish girl that candidly speaks about her growing up with SCID and the treatment she has received in the hospital; an immunology specialist discussing the condition; and the artist herself reading excerpts of H. C. Andersen’s Little Mermaid. The tent’s fabric suddenly transforms into a sea. The artist reads a bedtime story to the girl and tells us about transformation after treatment.

Figure 1: Visitors sitting on the bed inside the isolation tent.

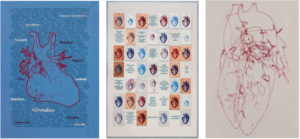

The second is a powerful presentation of different facets of congenital heart disease – its shape, its frailty, its treatment, its narrative. The piece mixes 3D printed models, set on a steel table, with large silk panels on which the journey of a patient is symbolized in its phases, from anatomy to medication to new technologies that can help diagnosis and therapy.

The installations show stylistic links with previous work by Sofie Layton, particularly her piece Bedside manners (Evelina Children Hospital, 2014), which also included a site-specific installation with a bed and a soundscape, her intent clearly that of making the installation as immersive an experience as possible for the viewer. In the current piece, for instance, entering the isolation tent involves wearing latex gloves, a mask and a plastic apron, all of which immediately heighten the awareness of the viewer around the medical issue.

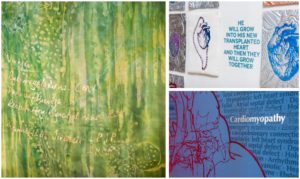

The artist has undoubtedly explored, appropriated and re-elaborated medical language in her process. Viruses’ names are scribbled in a doctor’s hurried handwriting on the fabric of the isolation tent, and language is central to the cardiac-themed piece, with five large silk panels listing congenital lesions, medications, technologies, but also keywords emerging from patients’ stories, all printed in the background of large anatomical drawings that, in turn, dialogue with the 3D anatomical models. Rather than a repetition of technical jargon, this creates an emphasis on the meaning and the power of these words – life-threatening conditions and life-saving medications, there shining on the precious silk backgrounds – technical/anatomical terms mixing with heartfelt imagery from patients’ narratives. Whilst the non-expert viewer would question the meaning of some of these words, the expert viewer would pause and wonder what stories are hidden behind and in between them. The language element is echoed in the soundscape, which opens with a young boy struggling to pronounce “ventricular assist device” (the boy, in real life, has been on mechanical heart support awaiting heart transplant).

Figure 2: Language is recurrent throughout the piece, such a name of viruses (left) and of cardiac conditions (bottom right), but also poignant quotations from parents and patients the artist has met during her residency (top right).

Another key element to the artistic research is an interesting exploration (microscopic and macroscopic) of shapes. On the one hand, viruses and cell structures are magnified. On the other hand, the anatomy of the heart and its variations in the presence of congenital lesions are beautifully presented with the use of 2D and 3D representations. The artist looks at the topography of the heart in a separate panel (exhibited in the entrance to Great Ormond Street Hospital), a rather abstract shape of intricate lines, a map, a blueprint of the engine room, but also suggesting other paths and other stories that have crossed. And 2D representations of the anatomy are complemented by the use of 3D models, manufactured from patients’ imaging data. Here the artist allows herself the license of going beyond the engineering aspect of 3D modeling, and includes in the cardiac landscape a small heart cast in bronze, which is suspended inside its bell jar – an evocative and immediate reminder of the preciousness of the organ.

Figure 3: A series of anatomical patient-specific models is presented under bell jars, including elements such as the suspended bronze heart (scaled from a medical model).

Layton’s work is exquisite in its layering. There is something rich and soft in the choice of silks. Something organic and fragile about the white 3D models. And a gentle lightness about the batiks of the isolation tent. But Layton’s work is above all exemplary in that is shows how art can be a powerful vehicle for sensitive stories charged with medical significance. The work is not sentimental or condescending and, albeit visually stunning, it does not embellish the pain of the stories it embodies. And equally it is not provocative, it does not intend to make the viewer uncomfortable by facing the complexity of rare diseases and the consequences on people’s lives. The work manages to strike a balance and what emerges, in the end, is a great respect for the humanity of the stories. The stories of patients, of course, but also the stories of their families, of physicians and their medical endeavors, and of researchers and scientists who look under the microscope in their daily practice.

Figure 4: Elements of the visual landscape of congenital heart disease. Left: one of five panels representing the journey of a patient, in this case medications, including a representation of a patient’s heart following multiple repairs of congenital lesions. Centre: a piece bringing together the voices of several patients and carers, every metal plate having been embossed by a different person with whom the artist developed a conversation during her residency. Right: representation of the topography of the heart.

The recognized importance of the narrative of illness experiences[1] is clearly central to the artist’s work, but so is the idea of the dialogue. The dialogue that she has had, through her participatory practice, with patients and families during workshops and on the wards of the hospital, over a period of several months. The dialogue that she has also fostered with researchers and clinicians, looking for that language she set out to explore in the first place, entering the lab herself and beginning to look under the microscope. This dialogue is completed with the inclusion of the viewer in the conversation, by means of the immersive nature of the pieces. The installations (both are site-specific for spaces in Great Ormond Street Hospital and the adjacent Institute of Child Health) rely on an array of media, including fabrics, embossed metals, the sculptural 3D models, but also soundscapes. The latter are absolutely integral to the installations and serve to further engage the viewer. Dr Jo Wray, health psychologist and senior research fellow at Great Ormond Street, remarked on the quality of the soundscapes, and how the looping of the recording is able to render the time element of living with rare diseases as something that represents itself day after day after day (for the patient but also for the carer). The viewer is thus included in the conversation and is also invited to look under the microscope. To look at the complexity of this world, crystalized in the technical jargon and juxtaposition of anatomical models – but also at the humanity that emerges so powerfully through the voices and through poetic quotations that the artist has blended in the pieces. “Now don’t suppose that there are only bare white sands at the bottom of the sea. No indeed! The most marvelous trees and flowers grow down there…” (H. C. Andersen)

Figure 5: Details of the isolation tent.

Note from the author: congenital heart disease is not, strictly speaking, a rare disease; however, some of the lesions depicted in Layton’s work represent cases of complex congenital heart disease and can be considered rare/unique in their anatomical arrangement.

Sofie Layton: http://www.sofielayton.co.uk

Go Create! Great Ormond Street Hospital arts programme: http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/about-us/our-priorities/go-create-arts-programme

Images courtesy of Stephen King. Do not reproduce without permission.

[1] Garden R. Who speaks for whom? Health humanities and the ethics of representation. Med Humanit 2015; 41:77-80