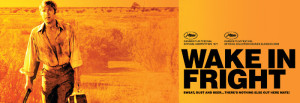

‘Wake in fright’ directed by Canadian director Ted Kotcheff’s film is considered a masterpiece for its innovative, daring storyline, psychological focus and exceptional visual imagery [1]. The film premiered in Cannes in 1971 to great critical acclaim, but in its homeland of Australia (where the film was set), it was poorly received.

The main objection to the film was its barbaric depiction of the Australian outback culture that was viewed as an offensive propagation of a stereotype. Subsequently all copies of the film were “lost”, with it never quite making it to VHS or DVD. In 2009, the Australian Film Archive acknowledged the wider importance of the film and located, then painstakingly restored, one of the few remaining prints [2, 3].

The story centres on the summer vacation of an eloquent British school teacher, John Grant (Gary Bond) teaching primary school children in the remote, desolate town of Tiboonda in Australia. He was sent there as part of a financial agreement to secure payment for his postgraduate education. As school term comes to an end, John begins his journey back to “the city”, fantasizing about an eminent reunion with his beautiful beau. A seemingly harmless stopover in the interchange town of Bundanyabba (“the Yabba”) leads to a spiral of disintegration.

In the Yabba, John meets various residents who feed into the trajectory of his decline. A local policeman, Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty), entices him into a series of drinks before introducing him to the local gambling culture. An initial win from a bet placed to humor his surrounding peers, leads to a compulsive urge to gamble more heavily. With the temptation of winning enough money to pay off his education and free himself from the enforced teaching duties, he goes on to lose all his money. From this point onwards, the teacher becomes entangled in a desperate struggle to escape. The more he tries to escape, the more he is drawn into excess drinking, gambling, hunting and brutal aggression, aided by the destructive presence of the ever intoxicated local medic, Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasance).

The film shows the teacher on a self-destructive journey, transitioning from the prototypic refined, reserved and well spoken “English gentleman” to an ever desperate “lout”. The narrative portrays the erosive nature of addiction, with our protagonist steadily losing control over his impulses, dignity and self-image. It shows a significant shift in John’s personal moral standards and values. Addiction is central to the change in his reference point of what is deemed acceptable ethically and professionally. One of the most shocking sequences in the film is a genuine, uncompromising footage from a night-time kangaroo hunt in the Outback. The director included this footage to highlight the cruelty of the hunting subculture by pushing the viewer to discomfort whilst being entangled in the masquerade of male bonding [4]. The inclusion of the hunt scene was likely a purposeful attempt by the director to create a metaphor for the teacher’s own confusing and conflicting experience. When the film screened in Cannes in 2009, twelve people walked out from the screening after the brutal hunt scene.

Kotcheff artfully balances the initial hedonistic allure of addiction with the corrosive reality which ensues. From a respected member of the community showing pompous disapproval of the barbaric, unrefined, local norms, the teacher becomes totally integrated into their customs to the point of losing his identity [4,5]. By the end of the film, the narrative quite poignantly highlights that the ultimate transformation through addiction is perhaps most shocking to the individuals themselves.

‘Wake in Fright’ allows the viewer to engage with the emotions of addiction vicariously. In playing with Jungian motifs [6], the film adds to its psychological impact. The unfolding chaos of the film’s narrative is played out in the context of the unforgiving gaze of the Australian Outback, arguably, the archetype of the disciplinarian “father”. Within the arc of the story, we witness the protagonist transitioning from the “soul image” archetypes (animus and anima) to those of “the shadow”. Initially, John Grant is presented as well spoken, patient and receptive (anima). He is simultaneously seen as strongly masculine, handsome, assertive and well educated (animus). As the film progresses, we witness a range of impulsivity (repetitive gambling), aggression (Kangaroo hunt, a drunken brawl), lust (a sexual encounter with a local’s daughter) and eventual self-sabotage (suicide attempt). All of these represent the emergence of undesired, socially unacceptable and usually disowned elements of one’s being, reflecting the surfacing of the “shadow” archetype. Essential to the social, physical, and moral degradation of the protagonist’s initially integrated self “persona”, is Doc Tydon, who represents the archetype of “the trickster”; a catalyst to self-destruction.

‘Wake in Fright’ is a rediscovered lost gem. In a similar vain to ‘Days of Wine and Roses’, it allows us to witness the conversion of an individual from sobriety to addiction; although in this case our protagonist appears in no way naive. The psycho-social circumstances leading to addiction preceding the narrative of decline distinguishes ‘Wake in fright’ from films such as ‘Leaving Las Vegas’, ‘Nil by mouth’, and ‘Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolfe’. Perhaps the film’s most powerful aspect is that, through its geographical and temporal setting, it inhabits a territory which although somewhat familiar, is alien enough to allow us to absorb the emotions and experience of addiction from a safe distance.

Address for correspondence: nadeem.psychiatrist@gmail.com

REFERENCES

[1] Wake in Fright (1971). Metacritic.com

http://www.metacritic.com/movie/wake-in-fright-1971

(accessed 12th October 2015)

[2] Ebert R. “Wake in Fright”. Roger Ebert.com. 31 October 2012

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/wake-in-fright-2012

(accessed 14 October 2015)

[3] Australian National Film & Sound Archive Annual Report. National Film & Sound Archive Australia. 2008-09

http://nfsa.gov.au/site_media/uploads/file/2010/11/03/08-09-Annual-Report.pdf

(accessed 14 October 2015)

[4] Skinner C. Ted Kotcheff discusses Wake in Fright, kangaroo slaughter and existentialism. Film Divider. 28th March 2014

(accessed 12 October 2015)

[5] Peary D. Ted Kotcheff on Wake in Fright. 5th October 2012. http://dannypeary.blogspot.com.au/2012/10/ted-kotcheff-on-wake-in-fright.html

(accessed 12 October 2015)

[6] Jung and Film: Post-Jungian Takes on the Moving Image. Hauke C, Alister I. London, England: Routledge Publishing Company , 2001