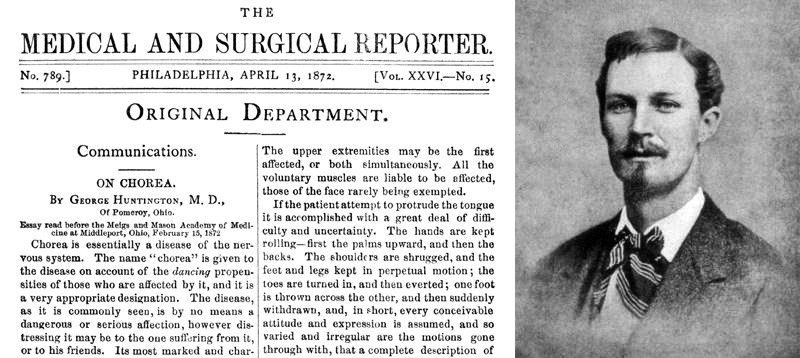

In George Huntington’s original clinical monograph (1872), changes in mental state and behaviour were particularly noted in his description of patients with Huntington’s disease (HD) [1]. Despite the fact that such symptoms are frequently the most disabling, the illness phenotype beyond that of motor symptoms remains less narrated. In part, this is perhaps because non-motor features are challenged by a number of difficulties, including in their identification, classification, and treatment. Resultantly, the neurobiological underpinnings of these symptoms and their impact on clinical outcomes in HD is currently unclear.

In the current month’s edition of JNNP, Connors et al explore this facet of HD, specifically probing psychotic symptoms [2]. The authors retrospectively analysed outcomes from the COHORT study, a large group of 1082 HD patients prospectively followed over 5 years [3], with the aim of characterising the clinical differences between patients with and without psychotic symptoms (i.e. delusions and hallucinations). The ~18% of patients who had psychosis demonstrated worse function, cognition and behavioural disturbances over time, in keeping with neurodegenerative literature. More unexpectedly however, motor features differed more favourably in this group, with patients demonstrating less chorea and a slower rate of development of choreiform movement, regardless of whether the psychosis was active.

The most recent decade has provided an enriched research climate in HD, which continues to expand with discoveries such as the location of genetic modifiers and the commencement of the first-in-human gene suppression trials [4]. In the setting of these potential novel treatment avenues, the findings of this study expose the neuropathological complexities of HD further, and spotlights the impact of this undeniably challenging psychiatric manifestation. The divergent motor profile found in these patients also warrants separate consideration, as this may propose a neurobiological link between the non-motor (psychosis) and motor (chorea) features, perhaps through an altered dopaminergic pathway. Looking forward, these findings must now be carefully dissected from the dose-related motor side-effects of antipsychotic medications and longer-term trajectories also need to be explored, particularly given that such features do not alter linearly with disease progression. Nevertheless, findings such as these will continue to build the complex disease framework that unites the motor and non-motor phenomenology of HD, adding clarity to both clinical outcomes and potential biological treatment targets.

Read more at https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/91/1/15

- Huntington G: On chorea. Med Surg Rep 1872, 26:317-321.

- Connors M, Teixeira-Pinto A, Loy C: Psychosis and longitudinal outcomes in Huntington disease: the COHORT Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 91:51-20.

- Investigators THSGC: Characterisation of a large group of individuals with Huntington disease and their relatives enrolled in the cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7:e29522.

- Consortium GMoHsD: Identification of genetic factors that modify clinical onset of Huntington’s disease. Cell 2015, 162:516-526.