The meta-analysis presented in the article ‘Cognitive-behavioural therapy does not meaningfully reduce depression in most people with epilepsy’ by Nobel and colleagues in this month’s October edition of JNNP explored the clinical impact of psychological treatment (cognitive-behavioural therapy, CBT) in patients with epilepsy. Specifically, findings from 5 randomised controlled studies that used CBT to treat depression or anxiety in such patients were pooled and rated against Jacobson’s Reliable Change Index to determine efficacy of treatment. The authors found that the changes of reliable improvement were significantly greater with CBT and that 30% of patients experienced ‘reliable improvement’, but 67% remain unchanged.

Overall, the authors suggest that although the difference with CBT is significant, the efficacy of treatment is not high. This raise some controversial points regarding the concept and definition of what should be regarded as efficacious treatment. However, separate to this issue, the study importantly emphasises the need to improve psychological treatment for such comorbidities, as is universally acknowledged. To achieve this however, the penultimate question that hinges upon the discovery of more effective treatment options remains largely unanswered: what is the neurobiology of psychiatric symptoms in epilepsy?

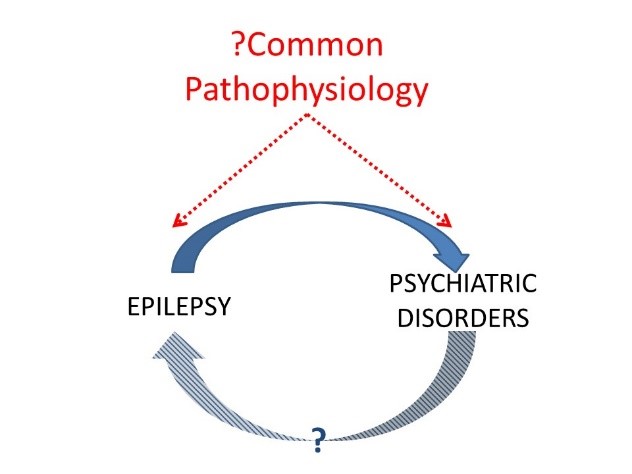

Although historical perception was that psychiatric comorbidities are secondary complications of seizure disorders, the relationship between psychiatric comorbidities and epilepsy is now known to be far more complex. In fact, although depression and anxiety are commonly linked with many different neurological disorders, the association between epilepsy and psychiatric symptoms appears to be unique and a bidirectional relationship has been postulated.

In support of this hypothesis, recent studies have demonstrated a significantly increased risk for the development of psychiatric symptoms in the 3 years before epilepsy onset and in the 2 years after epilepsy onset. A common underlying etiology of epilepsy and psychosis is also supported by the fact that the frequency of focal seizures, distribution of psychosis subtypes, and duration of psychotic episodes do not differ when comparing the symptoms preceding and following the epilepsy onset. Animal models of epilepsy have also exhibited behavioural abnormalities akin to psychiatric comorbidities in patients linked with altered monoamine neurotransmission, and predate the epilepsy in some cases. Overall however, until such mechanisms underlying this potentially reciprocal relation can be further unmasked, more effective treatment options may continue to remain elusive.