By Abraham Bergman, MD

Departments of Pediatrics of Harborview Medical Center and the University of Washington

I could not have had a more rewarding professional career. I joined the University of Washington pediatric faculty in 1964 and was based at two wonderful hospitals, Seattle Children’s for 18 years, and Harborview Medical Center for 30 years. Because both these institutions drew patients from a large region, I took part in the care of scores of injured children. This clinical work stimulated research on how these injuries might have been prevented. In 1985 I helped create the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center (HIPRC), and recruited Fred Rivara to direct it.

My particular interest was in planning and evaluating community interventions. Because I had long been involved in political campaigns I viewed the tactics aimed at changing health behavior little different from those used to win votes. A number of the efforts were successful; others were not. In this paper I describe 4 campaigns in the latter category, attempting to analyze the reasons for and implications of the disappointing results.

A National Bicycle Helmet Campaign That Never Happened

Disappointment: Failure to convince the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to lead a national bicycle helmet campaign.

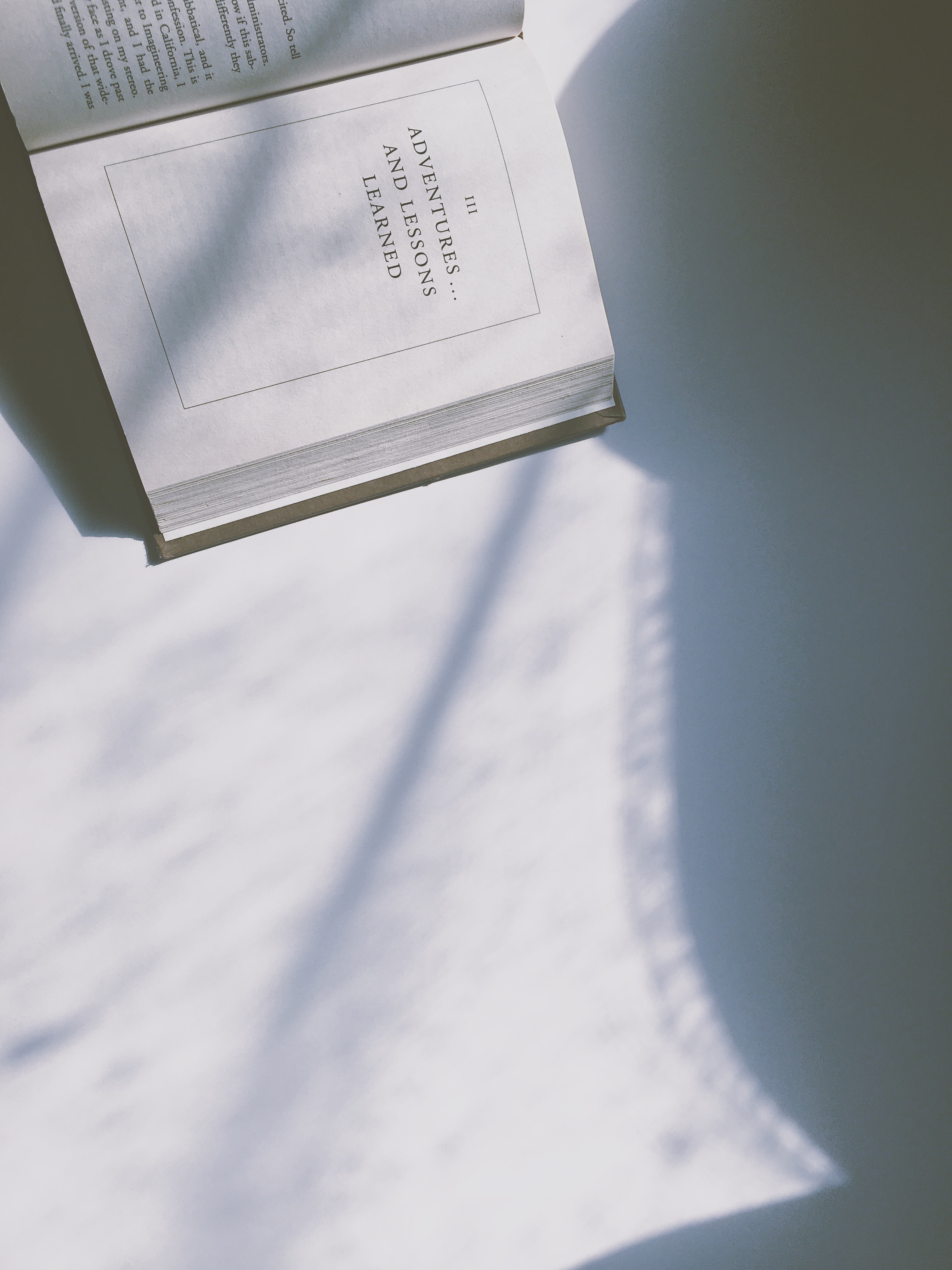

Background: In 1986 Rivara, and I launched a campaign to promote bicycle helmet usage in Seattle-area schoolchildren. Our stimulus came from caring for children with bicycle-related brain trauma. We started with a coalition consisting of pediatricians ( Washington State Chapter of the AAP), cyclists (Cascade Bicycle Club), and families of brain-injured children (Brain Injury Association of Washington). One of our posters is shows in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Unknown artist. Created for the Washington Bicycle Helmet Coalition

The campaign was successful. Over a 3 year period the sales of one brand of helmet rose from 1,500 to 22,000, and observed helmet usage rate among schoolchildren increased from 5% to 16%, as compared with a rise of 1% to 3% in a control community, Portland, Oregon.[1] A later unpublished survey in 1970 showed that the usage rate had grown to 70%. Most gratifying were subsequent studies showing a lower risk of head injuries in helmeted children[2] and a drop in hospital admissions of head injured children.3 The only significant cost was the part time salary of campaign coordinator. Given these results, replication in other communities seemed like a natural next step.

Our idea was for the AAP, in collaboration with the Brain Injury Association of American and the Bicycle Federation of American, to lead a national campaign. We envisioned that, similar to the Seattle effort, pediatricians in state and local communities would join with cyclists and families of brain- injured victims to promote helmet usage.

In 1990, Rivara and I presented the plan to the AAP’s Injury Prevention Committee We anticipated quick endorsement; we were wrong. Though there was no dissent about the need for children to wear bicycle helmets, consensus could not be reached on whether preventing bicycle head trauma should be an AAP priority As a result, no national campaign ever took place.

Conclusions: Brain injury treatment cannot reverse the effects of the injury itself; the only effective treatment is prevention. Promoting children’s bicycle helmets is one of the easiest of all injury prevention interventions. The protective effects have been clearly demonstrated, opposition is non-existent, coalitions are easily formed, and the costs are low. Why than do campaigns not undertaken? The inaction of the Injury Prevention Committee (now called the AAP Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention) is instructive. Members, appointed on a regional basis, have varying degrees of experience in injury prevention and often preferred issues of their own. The result is coming forth with “laundry lists” without prioritizing issues. Which translates to paralysis.

In a 1996 survey of children’s helmet usage. Rodgers found that less than one-fifth of children who rode bicycles wore helmets all or more than half of the time.[4] I can only speculate about the number of children that might have been spared from death and brain injuries had a national helmet campaign taken place.

The almost-successful campaign to control alcohol advertising in Washington State

Disappointment: In 1991 by a 2-1 vote, the Washington State Liquor Control Board turned down a petition by the Washington State Medical Association to place controls on the advertising and promotion of alcohol products.

Background: For many years I supervised an elective rotation for University of Washington pediatric residents in “advocacy,” One participant, Richard Shugerman, explored possible controls on “life-style” ads directed towards youthful beer drinkers. Given laws governing interstate commerce along with the economic-political power of the beer industry, the effort seemed quixotic. Until Shugerman came up with the wording of a little-known provision of the 21st Amendment to the Constitution that repealed prohibition in 1933. In order to the gain the votes of senators from states wanting to remain “dry,” states were given the right to govern all aspects of alcohol commerce. This resulted in a potpourri of state regulations. In an idealistic attempt to take politics out of the liquor business, Washington State removed authority from the legislature and placed it in the hands of a 3 member board appointed by the governor.

In 1990 the Washington State Medical Association, submitted a petition to the Board calling for “prohibiting ads implying that drinking enhances athletic ability or professional and social achievement.” Initially the petition was not taken seriously by the industry until a public hearing was scheduled. Only then did the implications of having to block ads in one state during national broadcasts became apparent. The hearing room on January 30, 1991 was packed. Executives of the major breweries descended on Olympia, state capital, Our message was delivered most powerfully by family members who had lost children from alcohol-related trauma. The petition was rejected by a vote of 2-1.

Conclusions: We did not expect to prevail; our proposal was too radical. But we were given the opportunity to document the pernicious “life-style” beer advertising that targeted youth. In our current legal climate that provides free-speech protection to commercials, no form of state control over liquor advertising can even be contemplated.

A Community Campaign to Promote Safe Storage of Firearms

Disappointment: Failure to carry out a campaign promoting the safe storage of firearms.

Background: In 2005 Grossman and colleagues at the HIPRC published a study showing that safe storage practices were associated with significant reductions in the risk of unintentional and self-inflicted firearm injuries and deaths among adolescents and children.[5] To put the research findings into practical use, we started planning of a community safe storage campaign.

“Safe storage” is a general term; we had to decide on the specific device to promote. The answer was provided by Dr. Jim Olson, then a pediatric resident taking an “advocacy elective.” Olson grew up in rural Michigan and was comfortable with firearms. He proceeded to interview a series of gun shop owners and police firearm instructors, asking a single questions: “what do you use at home for storing firearms?” emphatically Push-button lockboxes were preferred. They can be opened in the dark and do not involve keys, which are attractive to children.

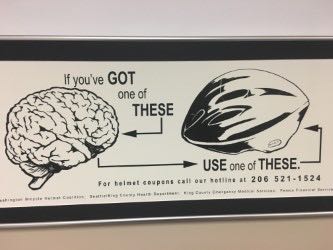

Replicating our experience with bicycle helmets, we began organizing a coalition. Key groups were health professionals, (especially trauma surgeons and ER physicians), police officers, and the families of firearm injury victims. Since our targets were firearm owners, we knew that spokespersons had to be individuals they trusted. We decided on police firearm instructors. Suicide prevention was a key theme. Our simple message—“buy a box for your gun, not for your kid”– is conveyed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Poster created by Ann Rhodes for the Harborview Injury 182 Prevention and Research Center

Our last challenge was raising $50,000. We failed. The gun rights organizations did not oppose us, but neither were they interested in giving money. The anti-gun forces. however, were actively opposed. A leader of Washington Cease Fire said: “such a campaign would be giving tacit approval for people to own guns.” That was it; the campaign never took place.

Fall prevention in the elderly

Disappointment: Failure to obtain funding for a campaign directed to senior citizens promoting the use of footwear that is light, easy to put on, and skid-resistant.

Background: With justification, fear of falling is omnipresent among the elderly. My interest came about from seeing improved mobility in my elderly parents when they began to wear running shoes with Velcro closures. This observation led to a survey in several local retirement homes on types of footwear being worn, Not surprisingly, the condition of women’s feet was worse than men’s, and they were more likely to walk in stocking or bare feet.[6] Two other studies by HIPRC colleges were then underway on the relationship of falls to footwear. [7] [8]

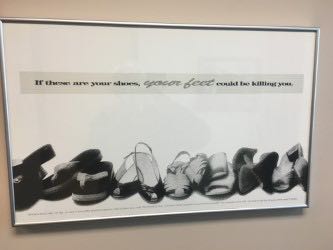

We started to organize a safe-footwear coalition involving health professionals, senior organizations, retirement communities, and footwear retailers. Our theme – “your shoes may be killing you” – is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Poster created by Ann Rhodes for the Harborview 210 Injury Prevention and Research Center

A curious episode then took place. The chief shoe buyer at Seattle-based Nordstrom’s, helped identify a safe-shoe prototype, and offered to buy a large supply from the maker. His offer was refused; “We’re not ready to market it yet,” he was told. He was astonished, as were we. At the time Nordstrom’s sold about one-quarter of all shoes marketed in the US.

Considering how athletic shoes could most rapidly find their way onto the feet of seniors, I fancied (truly!) a campaign sponsored by Nike. Meeting with several executives at their headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon, I said: “have you considered the untapped market potential of seniors?” With polite chuckles they demurred, saying, “we have invested too much in the youth market to change our focus.” In the end we could not come up with money to fund the campaign.

Safe footwear is still not actively promoted as a means of lowering the risk of fall injuries. In an extensive review of research studies, the US Preventive Services Task Force lists 7 interventions “possibly helpful “ to prevent falls in the elderly. Safe footwear is not among them.[9]

Conclusions: The Preventive Services Task Force did not endorse the intervention because there were no studies to prove its effectiveness. Which begs the question of whether randomized control trials must precede interventions. We initiated the Seattle children’s bicycle helmet campaign 4 years before their effectiveness in reducing brain injuries was demonstrated. There comes a point when common sense should prevail. Not for a moment do I espouse substituting fervor for scientific evidence. But safe footwear, like seatbelts, cycling helmets, and life-vests, is an intervention that costs little, does no harm, and should not be ignored.

Summary

Success in injury interventions requires passion, skill, public support, and money. Passion usually comes from contact with injury victims, either in their care or from personal relationships. The needed skills are identical to those required in political campaigns. The objective in one is to secure votes; in the other to induce health-enhancing behaviors. Public support and money go together; in the injury field there is a shortage of both. Mostly because there is no constituency. As a general group, injury victims do not band together. A closer alliance of those who care for injured patients, those who conduct injury research, and those who are victims of injuries would help attract more support.

References:

1.Bergman AB, Rivara FP, Richards DD and Rogers LW. The Seattle children’s bicycle helmet campaign. Am J Dis Child 1990; 144:727-731

2. Rivara FP, Thompson DC, Thompson RS, Rogers LW, Alexander B, Felix D, Bergman AB. The Seattle children’s bicycle helmet campaign: changes in helmet use and head injury admissions. Pediatrics. 1994 Apr;93(4):567-9.

3. Thompson, DC, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Effectiveness of bicycle safety helmets in preventing head injuries. A case-control study. JAMA. 1996 Dec 25;276(24):1968-73.

4. Rodgers GB.Bicycle helmet use patterns among children. Pediatrics. 1996 Feb;97(2):166-73.

5. Grossman DC. Mueller, BA, Riedy, C et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintended firearm injuries. JAMA 2005 Feb 9. 292 (6) 707-14.

6. Dunne RG, Bergman AB, Rogers LW, Inglin B, Rivara FP. Elderly persons’ attitudes towards footwear – a factor in preventing falls. Public Health Rep 1993; 108(2):245-248.

7 Koepsell TD, Wolf ME, Buchner DM, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, Tencer AF, Frankenfeld CL, Tautvydas M, Larson EB. Footwear style and risk of falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Sep;52(9):1495-501.

8. Tencer AF, Koepsell TD, Wolf ME, Frankenfeld CL, Buchner DM, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, Larson EB, Tautvydas M. Biomechanical properties of shoes and risk of falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Nov;52(11):1840-6.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Intervention to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults.[published online April 17, 2018] JAMA.doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3097.