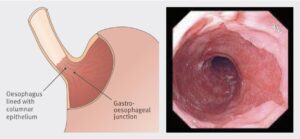

Getting surveillance for Barrett’s oesophagus (BO) right is critical for early detection and prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. When identified early, Barrett’s can be treated effectively with minimally invasive endoscopic techniques. Despite clear national guidelines on when and how to perform surveillance for BO, adherence to these guidelines is variable.

In the most recent edition of Frontline Gastroenterology, Ratcliffe et al. present an impressive 5-year retrospective comparative cohort study to answer the question whether a dedicated BO surveillance service offers a higher dysplasia detection rate (DDR) when compared to patients who underwent BO surveillance We dive deeper into the article in this blog, and ask what the implications are for the future of BO surveillance nationally.

What did we know already? The same group from Salford have previously demonstrated that a dedicated service improves adherence to BSG guidelines on surveillance of BO when compared to patients with BO undergoing surveillance on a non-dedicated list, albeit with a similar rate of identification of both intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia or OAC.

In the current paper, the authors look retrospectively at 921 BO procedures performed on 678 patients over a 5 year period, and compare those performed on a dedicated BO list with those performed on any other endoscopy list (62% vs 38%). They primarily compare dysplasia detection rate (DDR), along with guideline adherence and several other factors which may influence DDR.

These dedicated lists are differentiated by three factors: endoscopist experience, time per procedure, and, of course, being a dedicated list. All OGDs were performed by one of three gastroenterology higher trainees or consultants, all with training in BO lesion recognition, and crucially who all do a high volume (>100) of BO procedures annually. All BO procedures were given 1.5 ‘units’ (or ‘points’), which equates roughly to 30 minutes per procedure, with 2 units (40 minutes) given to patients where BO segments were known to exceed 10cm in length. Finally the differentiated nature of the procedures should not be overlooked – if it’s on the list, it’s going to be BO!

The headline result is that DDR was higher in the group undergoing dedicated BO surveillance endoscopy compared to those on standard endoscopy lists (6.3% vs. 2.7%, p = 0.014). Across all six aspects of the BSG minimum dataset for BO endoscopy reporting (e.g. documentation of Prague classification and presence or absence of visible lesions, adherence to Seattle protocol), the dedicated BO lists significantly outperformed standard lists. Use of narrow band imaging, acetic acid and targeted biopsies were also higher on the BO lists.

The authors recognise the limitations of the current study. Having a dedicated BO service is atypical, and aside from having specific training for those on the BO list, it was not possible to determine the prior experience of all endoscopists involved in the study. Also, being non-randomised, there is a risk that patients with longer segments of BO (and therefore a higher risk of dysplasia) were scheduled on the dedicated list. This notwithstanding, the results are compelling that in a non-tertiary, real-world setting, running a dedicated BO service improves DDR and adherence to national guidelines.

So what are the barriers to implementation? First and foremost we need to have good quality evidence that such a dedicated service or programme improves outcomes for patients. This study neatly lays the groundwork for a randomised controlled trial to answer this very question. If this is the case, we will also need to know that running a dedicated service is a good use of resources: even if proven to be more effective, good quality BO surveillance takes time, which equates to endoscopy capacity being taken away from other stretched sectors such as Two Week Wait investigations and the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP). Finally, there is the ‘how’. Will such a programme be nationalised, like with BCSP? Will dedicated BO surveillance endoscopists need to pass an assessment and continue to achieve certain Key Performance Indicators to maintain their accreditation? These are all conversations yet to be had.

Overall this is a really exciting topic, and we would highly recommend reading this ambitious and well-written paper in the current issue of FG.

References

- Lipman G, Haidry RJ. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s and early oesophageal neoplasia. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017;8(2):138-142. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2016-100763

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63(1):7-42. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372

- Ratcliffe E, Britton J, Yalamanchili H, et al. Dedicated service for Barrett’s oesophagus surveillance endoscopy yields higher dysplasia detection and guideline adherence in a non-tertiary setting in the UK: a 5-year comparative cohort study. Frontline Gastroenterology Published Online First: 10 August 2023. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2023-102425

- Britton J, Chatten K, Riley T, Keld RR, Hamdy S, McLaughlin J, Ang Y. Dedicated service improves the accuracy of Barrett’s oesophagus surveillance: a prospective comparative cohort study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019 Apr;10(2):128-134. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101019. Epub 2018 Sep 5. PMID: 31205652; PMCID: PMC6540283.

Author: Dr James Kennedy (Trainee Associate Editor)

Twitter: @DrJMKennedy

Declarations: I am a trainee associate editor for Frontline Gastroenterology