Alex Pinto, PhD student, School of Healthcare, University of Leeds

Twitter: @alexpinto50

What do you think about when you look at this picture of a graveyard? What type of feelings does it conjure up for you?

What do you think about when you look at this picture of a graveyard? What type of feelings does it conjure up for you?

For many people within our contemporary western society, death and dying tends to be associated with negative feelings. However, for some people understanding and accepting their own mortality can be empowering, even enlightening. For me, death for many years made me frightened. Just as I would fall asleep, I would suddenly become fully awake panicking about what would happen if I died that night – I worried that I would miss the drive into work and that I would miss being with my friends and family. So many things crossed my mind and it took a while before I could settle and actually fall asleep. But death to me now is so very different. I have been through a number of experiences, as we all do as we travel through life, but after working with people who were dying, I realised something very profound. I had a completely different outlook on death and life. It had been a privilege, and a humbling experience, to take care of people who were dying, and to support their families. It was through this experience that I ended up going to university to understand more about why we behave the way we do about death and dying.

I found so many psychological theories that help to explain our fears, our behaviours and our thoughts around death and dying. But it was reading an article by Dr Paul T Wong, a Canadian Psychologist, showing that death and dying could be seen in a more positive light, that had a huge impact on me and my research. Here was something that put into words what I was thinking and feeling. He conceptualised a theory called Meaning Management Theory (MMT: Wong 2008). He argued that meaning in life and acceptance of death are intertwined. The theory focuses on managing our inner life; all our hopes, dreams, aspirations, regrets, doubts, hates and beliefs. MMT is based on how people attach meanings to other people or events that happen in everyday life, suggesting that by enabling these feelings we could create a more meaningful, fulfilled life. This article led me to research further into death and dying and positive psychology.

acceptance of death are intertwined. The theory focuses on managing our inner life; all our hopes, dreams, aspirations, regrets, doubts, hates and beliefs. MMT is based on how people attach meanings to other people or events that happen in everyday life, suggesting that by enabling these feelings we could create a more meaningful, fulfilled life. This article led me to research further into death and dying and positive psychology.

In 1998, when Martin Seligman gave his inaugural speech as president of the American Psychological Association, he introduced the concept of positive psychology. The concept of positive psychology, spearheaded a change in direction of research within psychology, with a paradigm shifting from the deficits of human thoughts and behaviours to exploring what is good or positive about people, their thoughts and behaviours. The main focus of positive psychology is on the positive events and influences that occur in an individual’s life (Seligman, 1999). Positive psychology also recognises the interplay between positive and negative phenomena. Whilst this was recognised implicitly within positive psychology, Second Wave Positive Psychology or Positive Psychology 2.0 involves making the interplay between the negative and positive phenomena explicit. Second Wave Positive Psychology/Positive Psychology 2.0 is still positive psychology but it acknowledges that sometimes the darker side of life should be acknowledged (for example, death and terminal illness) to better understand existential phenomena (Wong, 2011; Ivtzan et al. 2016). In Second Wave Positive Psychology/Positive Psychology 2.0 it is believed that people should embrace both the positive aspects of living, such as love, happiness and gratitude, and the negative aspects of life, such as terminal illness, suffering and death. This, may in turn, allow for people to change, grow and develop. Second Wave Positive Psychology/Positive Psychology 2.0 builds on existing knowledge about human resilience, growth and strength, complimenting current psychological views.

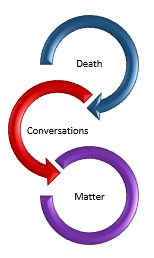

What I have found during my research is that most of the empirical evidence I have found suggests conversations of death and dying can have a number of benefits. However, the current evidence base is clinically focused with very little empirical evidence based in a non-clinical setting. My PhD at Leeds University is investigating conversations about death and dying, and will provide empirical evidence for the need to have open and frank conversations regarding death and dying whilst we are healthy.

Death is inevitable, but having a more positive relationship with our mortality, could allow us to embrace life more fully no matter what the circumstances. It is about living despite what adversities or traumatic events we face. By living fully, embracing all life has to offer, the perceived ‘good’ and ‘bad’ could enhance our relationships with others, and enhance our sense of self and wellbeing. Having a more positive perspective towards death and dying could provide the motivation to go for a higher level of life satisfaction and provide meaning to our lives.

Further reading

If you want to know more about death positivity, the following websites are worth a look…

References

Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2016). Second wave positive psychology. Oxon: Routledge.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). Positive psychology network concept paper. Retrieved from https://www.sas.upenn.edu/psych/seligman/ppgrant.htm

Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & P. T. P. Wong (eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp.65-87). New York: Erlbaum.

Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive Psychology 2.0; Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.