Dr Maria Clark is a Lecturer in Nursing in the School of Nursing (Institute of Clinical Sciences) University of Birmingham, U.K.

Paving the way

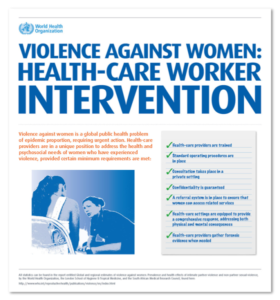

In May 2016, the World Health Assembly Member States pledged a global plan of action on strengthening the role of the health systems in addressing interpersonal violence, particularly against women and girls and against children. The international Nursing Now! movement seeks to engage all nurses in realising their role in addressing global health challenges (Crisp, 2018). Domestic violence and abuse (DVA) prevention is a global public health priority with important implications for nursing (Bradbury-Jones et al, 2017; Bradbury-Jones & Clark, 2016). DVA is described as ‘any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. The abuse can encompass but is not limited to: ‘psychological, physical, sexual, financial [or] emotional’ (Home Office 2012). Worldwide, 1: 3 women are estimated to experience DVA across a lifetime and there is ample evidence to suggest how and why nurses should incorporate DVA assessment into their practice, providing certain requirements can be met (WHO et al, 2013).

Setting standards for healthcare intervention (WHO, 2013)

Undertaking conversations about DVA means recognising that while it is generally understood to relate to adults over 16 years of age, it can impact upon anyone at any age or stage of their lives. Some populations are especially at risk. Women, children, and disabled people are disproportionately affected (Taylor et al, 2013). Health care workers should be trained to intervene with standard operating procedures in place (WHO, 2013. U.K NICE, 2014. U.K Department of Health, 2017). Nurses may also be involved in providing forensic evidence. Not all injuries are visible, however, and not all nurses are skilled in recognising the multiple complex problems associated with DVA. In the UK, the Identification and Referral for Intervention and Safety ( IRIS) programme shows success in in training primary care doctors (GPs) in brief interventions for DVA reduction (Bradbury-Jones et al, 2017). In the U.K Health Visitors are especially called to action on DVA reduction due to their long term specialist nursing work with children and families. All nurses could be better prepared to recognise the signs, ask questions and preserve safety for women and children.

Learning from ADOVIC in Jinja, Uganda

Recently, I was fortunate to travel with senior colleagues from the Risk, Abuse and Violence research programme theme on an international research trip to East Africa. The trip was funded by the University of Birmingham’s Institute for Global Innovation. Nested within a broader research agenda on Transnational Crime and Gender-based Violence, one of our project aims was to engage with an ‘Anti-Domestic Violence and Abuse Coalition (ADOVIC)’ situated in the city of Jinja, in Uganda. Our preliminary engagement was facilitated by email, Skype, WhatsApp and telephone conversations in advance of the visit. Warmly welcomed when we arrived, we undertook three visits to the ADOVIC host office-base, undertaking rich face to face conversations in a short space of time. We identified mutual research priorities in linking maternal and child health strategies for DVA reduction. Most importantly we established that we wanted to continue the conversation, working together from a distance.

Preserving safety

Back in the UK, learning to support people going through DVA is still uncharted territory for many nurses. Often described as a ‘long road to freedom’ the route to safety is not straightforward. Adopting a trauma-informed approach to health assessment is important; asking the question ‘what has happened to you’ allows a more open space for disclosure wherever abuse is suspected (Bradbury-Jones & Clark, 2016). Are you safe? is another useful question. Domestic abuse or violence is a crime and should be reported to the police – there are organisations who can offer help and support. In the U.K , calling 999 in a domestic abuse emergency, sharing the national emergency DVA hotline and collaborating with the independent sector (such as Women’s Aid and the Freedom Programme) is a good starting point, relevant to all nurses working in health and social care.

My experience of abuse disclosure in different contexts is supported by research which suggests that women do want to be asked about abuse (Taylor et al, 2013, Bradbury-Jones et al, 2016). Abuse, however, is a complex experience and as such it may be disclosed without words in brief, silent moments where a human gesture or cue might ‘say’ more. Whichever way disclosure is enabled, and support services put in place, there may be no way of knowing whether the conversation helped preserve safety and if it did so, how? This is a research challenge. Breaking the intergenerational cycle of violence as best we can is vital to reducing the major long term physical and mental health impacts of DVA (Walby & Allen, 2004). All nurses can play a part in this global health challenge; applying knowledge and skills about DVA reduction within and beyond the local healthcare encounter.

Calling the National Domestic Violence Helpline

The 24hr freephone National Domestic Violence Helpline (run in partnership between Women’s Aid and Refuge) is available on 0808 2000 247 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

References

Bradbury-Jones, C., Clark, M.T. & Taylor, J. (2017) Abused women’s experiences of a primary care identification and referral intervention: A case study analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13250

Bradbury-Jones, C. & Clark, M.T. (2016) Intimate partner violence and the role of community nurses. Primary Health Care, 26(9), 42-48.

Bradbury-Jones, C. & Clark, M.T. (2016) How to address domestic violence and abuse. Nursing Times, online issue, 12, 1-4.

Bradbury-Jones, C., Clark, M.T., Parry, J. & Taylor, J. (2016) Development of a practice framework for improving nurses’ responses to Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.13276

Crisp, N (2018): Nursing Now – why nurses and midwives will be even more important and influential in the future, International Nursing Review, June 2018 pps 145-7, Vol 65, no 2 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/inr.12463

Taylor, J., Bradbury-Jones, C., Kroll, T. & Duncan, F. (2013) Health Professionals’ Beliefs about Domestic Abuse and the issue of Disclosure: A Critical Incident Technique Study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(5), 489-499

U.K Department of Health ( 2017) Domestic abuse: a resource for health professionals; Information to help all NHS staff and allied healthcare partners in their response to victims of domestic violence and abuse. Accessed online 09.11.18 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-a-resource-for-health-professionals

U.K Home Office (2012) Circular 003/2013: new government domestic violence and abuse definition. Accessed online 11.11.18,.www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-government-domestic-violence-and-abuse-definition

U.K National Institute for Health and Social Care ( NICE) (2014) Public health guideline [PH50]. Domestic violence and abuse: multi-agency working Accessed online 09.11.18 https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/PH50

Walby S, Allen J. Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: finding from the British Crime Survey. Home Office Research Study 276. London, Home Office, 2004

World Health Organisation (2013) Responding to to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines . Accessed online 09.11.18 WHO http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241548595/en/

World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence, Accessed online 09.11.18 http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures