Health care needs a new way to measure success – one that values what actually produces health.

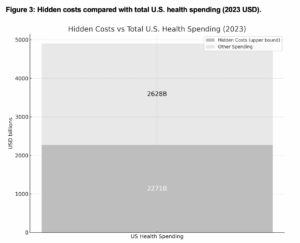

For decades, financial flows – revenues, reimbursements, spending and productivity – have dominated how modern industrialized nations judge success in health care. But these measures conceal the healthcare system’s most consequential losses: worsening patient outcomes and eroding trust, workforce burnout and turnover, persistent inequities, and growing climate harms. In the United States alone, when the “off-balance-sheet” costs are made visible, conservative estimates suggest that they total $2.05-2.27 trillion annually – roughly 42-46% of all U.S. health spending in 2023 ($4.9 trillion) (see Figure 1, and comparison with total spending in Figure 3).^1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

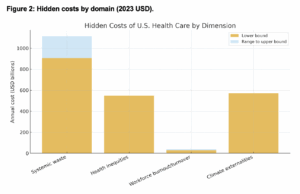

This total reflects the aggregation of established estimates: waste ($906-1,114B), inequities ($547B), workforce turnover and burnout ($29-40B), and healthcare’s climate externalities ($570B). These figures are conservative, exclude overlaps, and capture only direct costs – meaning the true losses are likely even higher. They must be considered when we ask whether current spending figures are “worth it” for the outcomes we achieve.

A New Measure of Success

A useful parallel comes from economics. The concept of “inclusive wealth” moves beyond GDP to account for natural, human, and produced capital (Dasgupta et al 2021). Applied to health care, success should be measured by whether systems are sustaining – or eroding – the assets they depend on.

New metrics must reflect:

- Patient health and trust as core assets;

- Workforce wellbeing as infrastructure;

- Equitable care as both moral and economic imperative;

- Responsible innovation grounded in evidence;

- Environmental impact as a performance indicator.

This reframing would expose the hidden costs of neglect and reorient leadership and investment toward sustained resilience (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The Hidden Balance Sheet of U.S. Health Care

Hidden costs of U.S. health care: $2.05-2.27 trillion annually (adjusted to 2023 dollars) (roughly 42-46% of total U.S. health spending in 2023)

-

-

-

-

-

- Systemic waste & low-value care: $906-1,114B

- Health inequities: $547B

- Workforce burnout & turnover: $29-40B

- Climate externalities: $570B

-

-

-

-

Bottom line: Even with conservative estimates, U.S. health care is depleting its “health capital” – patients’ outcomes and trust, workforce wellbeing, population health, and climate resilience – without accounting for the loss.

Note: Spending on artificial intelligence in healthcare is estimated at approximately $13 billion in 2024, reflecting rapid market expansion. However, current evidence of net benefit or harm remains limited; therefore, AI-related expenditures are not included in the hidden total costs.

Inflation Adjusted Using Consumer Price Index – Urban Consumers to 2023 U.S. Dollars

Notes on Calculations in Figure 2.

-

-

-

-

- All CPI values are BLS CPI-U annual averages. Inflation base year: 2023 USD.

- Waste: Shrank et al., JAMA 2019 ($760-$935B, 2019 USD).

- Inequities: LaVeist et al., JAMA 2023; racial & ethnic burden $451B, 2018 USD.

- Workforce RN turnover: NSI 2025; $3.9-$5.7M per hospital. Hospitals=6,120 (AHA FY2022). Back-cast to 2023USD using 2023/2024 CPI ratio.

- Workforce physician burnout: Han et al., Ann Intern Med 2019; $4.6B, 2019 USD.

- Climate: 610 MtCO2e (Eckelman et al., Health Affairs 2020). SCC range $51-$190 per ton (2020$) converted to 2023 USD and multiplied by emissions.

- Totals sum low and high bounds after converting each component to 2023 USD.

-

-

-

Where Costs Accumulate: What GDP Hides in Health Care

Economists have urged governments to rethink what counts as economic success (Dasgupta, 2021). In 2021, Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta reframed prosperity by showing how gross domestic product hides depletion of natural assets, and by treating nature as free and limitless, our economic systems will ultimately erode their very foundations.

A similar reckoning is needed in U.S. health care. Including only financial measures such as total spending on health care (about 18% of the U.S. economy), many believe we are already failing to achieve outcomes worthy of this level of investment. Yet, the costs are much higher than the numbers suggest, and our spending figures hide what matters most: people’s health, the workforce, social trust and environmental resilience. In effect, we are running down the resources we need to produce health – and the costs are mounting.

What appears as financial growth may, in fact, be systemic depletion. Leaders who rely on narrow financial metrics risk mistaking fragility for performance – and investing in strategies that undermine long-term resilience. Only by valuing what matters to population health can the healthcare industry secure resilience, trust, and long-term prosperity.

Patients: Outcomes and Trust

The U.S. spends more per capita on health care than any other nation, yet outcomes lag far behind peers. Life expectancy, maternal mortality, and preventable deaths all paint a bleak picture. Meanwhile, trust in health care continues to erode, driven by misinformation, fragmented care, and persistent inequities. These losses are rarely counted as “costs,” but they directly reduce health care’s ability to deliver health. (Figure 1 summarizes how these unmeasured losses add up.)

Workforce: Burnout and Turnover

Economic prosperity depends on balancing demand with nature’s regenerative capacity (Dasgupta, 2021). In health care, that capacity is our workforce – and we are exhausting it. Burnout, moral injury, and workload burdens are driving record turnover. Replacing a bedside nurse costs an average of $61,110; replacing a physician can range from $500,000 to over $1 million.^5,6 Hospitals lose between $3.9-$5.7 million per year due to nurse turnover (excluding agency/travel staff), while physician burnout costs the U.S. health system about $5.48 billion each year (2023 USD).^5,6 The cost of an early retirement or a career switch out of health care is borne by those left behind – speeding the feedback loop of burnout and overwhelm, depreciating of our most critical asset: people.

Disparities: Unequal Health Capital

Just as ecological degradation harms the poorest, the failures of U.S. health care fall hardest on marginalized communities. Structural racism, underinvestment in primary care, and inequities in insurance perpetuate disparities that carry an annual economic burden of roughly $547 billion (2023 USD, inflation-adjusted from the original $451 billion estimate).^2,3,4 These inequities represent squandered human capital – vast pools of potential left unrealized – and a national workforce full of people who are sick is less productive.^9

Technology: Promise and Peril of AI

The rush to adopt artificial intelligence mirrors unsustainable subsidies in other sectors: potentially transformative, yet risky. Many tools enter practice without robust evidence or safeguards against bias. High costs and inequitable access risk widening disparities rather than closing them. Without careful governance, investments in experimental technology could consume resources better spent on proven, evidence-based care. (AI is not included in the totals shown in Figure 1, which reflect established estimates for other domains.)

Climate: Health Systems on the Frontline

Hospitals are vulnerable to floods, fires, and storms. At the same time, health care contributes nearly 9% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, generating an estimated 610 million metric tons of CO₂e annually.^7 Poor air quality leads to increases in asthma and other chronic conditions; health system commitments to reducing emissions are gaining traction.^10 Unless climate resilience becomes central to planning, health care will remain both a victim and a driver of crisis (see Figure 2 for the climate externality estimate and Figure 3 for scale relative to total spending).

Health care is embedded within the health of patients, providers, communities and the environment. To ignore these foundations is economically reckless. It is time to expand our definitions of cost in health care and shift to measures of outcomes, workforce sustainability, equitable care and environmental stewardship. Only then will we truly see – and account for – the true cost of care.

Inflation Adjusted Using Consumer Price Index – Urban Consumers to 2023 U.S. Dollars

Notes on Calculations in Figure 3.

-

-

-

- All CPI values are BLS CPI-U annual averages. Inflation base year: 2023 USD.

- Waste: Shrank et al., JAMA 2019 ($760-$935B, 2019 USD).

- Inequities: LaVeist et al., JAMA 2023; racial & ethnic burden $451B, 2018 USD.

- Workforce RN turnover: NSI 2025; $3.9-$5.7M per hospital. Hospitals=6,120 (AHA FY2022). Back-cast to 2023USD using 2023/2024 CPI ratio.

- Workforce physician burnout: Han et al., Ann Intern Med 2019; $4.6B, 2019 USD.

- Climate: 610 MtCO2e (Eckelman et al., Health Affairs 2020). SCC range $51-$190 per ton (2020$) converted to 2023 USD and multiplied by emissions.

- Totals sum low and high bounds after converting each component to 2023 USD.

-

-

Learning Points

- Financial metrics conceal hidden losses. Like GDP in economics, revenues and reimbursements in health care disguise the erosion of outcomes, trust, and resilience.

- Hidden costs are vast. Waste, inequities, burnout, and climate externalities total $2.05-2.27 trillion annually, approaching half of U.S. health spending (2023).

- Workforce depletion is unsustainable. Burnout and turnover represent billions in avoidable costs and threaten system stability.

- Environmental and population health are economic imperatives. Disparities and health-sector emissions undermine justice and prosperity.

- New measures of success are urgent. Health care must move beyond financial growth to metrics of outcomes, workforce wellbeing, population health and climate resilience.

Selected References

- Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. “Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings.” JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509.

- Waidmann TA, et al. “The Economic Burden of Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities in the United States.” Urban Institute; 2009.

- LaVeist TA, Pérez-Stable EJ, Richard P, et al. “The Economic Burden of Racial, Ethnic, and Educational Health Inequities in the US.” JAMA. 2023;329(19):1682–1692.

- Lavizzo-Mourey R, Besser R, Williams D. “Understanding and Mitigating Health Inequities.” N Engl J Med. 2021;383:1681-1684.

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. “Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States.” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2019;170(11):784-790.

- NSI Nursing Solutions. “2025 NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report.” NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. 2025.

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, Senay E, Dubrow R, Sherman JD. “Health Care Pollution and Public Health Damage in the United States: An Update.” Health Affairs. 2020 Dec;39(12):2071-2079.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). “National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet, Historical NHE 2023.” Baltimore, MD: CMS, 2025.

- Goetzel RZ, et al.“Health, Absence, Disability, and Presenteeism Cost Estimates of Certain Physical and Mental Health Conditions Affecting U.S. Employers,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46 (April 2004): 398-412.

- Pollack, R. “AHA Statement on HHS Pledge Initiative to Mobilize Health Care Sector to Reduce Emissions.” American Hospital Association. April 22, 2022.

All References

- Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. “Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings.” JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.13978. Available at: JAMA.

- Waidmann TA, et al. “The Economic Burden of Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities in the United States.” Urban Institute; 2009. Available at: Urban Institute.

- LaVeist TA, Pérez-Stable EJ, Richard P, et al. “The Economic Burden of Racial, Ethnic, and Educational Health Inequities in the US.” JAMA. 2023;329(19):1682–1692. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5965. Available at: JAMA.

- Lavizzo-Mourey R, Besser R, Williams D. “Understanding and Mitigating Health Inequities.” N Engl J Med. 2021;383:1681-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2008628. Available at: NEJM.

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. “Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States.” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2019;170(11):784-790. doi:10.7326/M18-1422. Epub 2019 May 28. PMID: 31132791.

- American Medical Association (AMA). “Cost analysis examines primary care physician turnover due to burnout.” 2022. Available at: AMA Press Release.

- NSI Nursing Solutions. “2025 NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report.” NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. 2025. Available at: NSI Report PDF.

- Jeppson J, Anderson J. “KLAS Research Collaborative: Clinician Turnover 2024 Report.” KLAS Research, 2024. Available at: KLAS Research.

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, Senay E, Dubrow R, Sherman JD. “Health Care Pollution and Public Health Damage in the United States: An Update.” Health Affairs. 2020 Dec;39(12):2071-2079. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01247. Available at: Health Affairs.

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, Ashby B, Steele K. “Health Care’s Climate Footprint Report.” Health Care Without Harm. 2019. Available at: Health Care Without Harm.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Center for Environmental Economics Office of Policy, Climate Change Division Office of Air and Radiation. “Report on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases: Estimates Incorporating Recent Scientific Advances.” Washington, DC: EPA, 2023. Available at: Environmental Protection Agency.

- Seervai S, Gustafsson L, Abrams M. “How the U.S. Health Care System Contributes to Climate Change.” Commonwealth Fund, 2022. Available at: Commonwealth Fund.

- Nguyen T. “Decoding the Cost of Implementing AI in Healthcare.” Blog article, NeuronD, 2023. Available at: NeuronD.

- Kharychkova, A. “The Real Cost of Implementing AI in Healthcare.” Blog article, Orangesoft, 2025. Available at: Orangesoft.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). “National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet, Historical NHE 2023.” Baltimore, MD: CMS, 2025. Available at: CMS.gov.

- Goetzel RZ, et al.“Health, Absence, Disability, and Presenteeism Cost Estimates of Certain Physical and Mental Health Conditions Affecting U.S. Employers,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46 (April 2004): 398-412. Available at: California State Water Resources Control Board.

- Pollack, R. “AHA Statement on HHS Pledge Initiative to Mobilize Health Care Sector to Reduce Emissions.” American Hospital Association. April 22, 2022.

- Dasgupta P. “The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review.” London: HM Treasury, 2021. Available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Authors

Kate B. Hilton, JD, MTS

Kate works at the intersection of health system leadership, workforce sustainability, and equity as a Co-Founder and Principal of Innovation Capital, a healthcare and social impact firm committed to building human and social capital for innovation at scale.

Carrie Colla, PhD

Carrie is a health economist and professor whose research focuses on health care delivery reform and system performance at Dartmouth College and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice at the Geisel School of Medicine.

Declaration of Interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.