“There is no exercise better for the heart than reaching down and lifting people up”

John Holmes

One of the most joyful things about choosing to practice with care and kindness in our work as health professionals as well as in our personal lives, is that kindness can lift us up just as much as it does the recipient of our actions. Moreover, there is no need to wait until someone appears to be suffering, to return them to a baseline of normal functioning, to choose to act with kindness. Kindness is one of the greatest tools humanity has on offer to encourage flourishing beyond baseline, for both the giver and the receiver. We can bring people along on our journey, and our capacity for kindness is limitless, if we choose to embrace this mindset.

With increasing momentum, the science and art of kindness and caring in health has entered our institutional, political, community and personal awareness. After years of pandemic, health system reformations, unprecedented pressures on hospital systems and the people who work within the wider system, what the world most needs now is kindness. Global movements in kindness in healthcare are edging ever closer to the mainstream spotlight. For the first time in medical and health science focused conferences, the words kindness, love, compassion, vulnerability, trust and wellbeing are no longer whispered, but said with pride.

If there is a silver lining with the pandemic it is the new ease, comfort and flexibility we have in connecting with one another around the globe. Meetings are no longer simply face-to-face affairs. We can and do connect with one another over online forums, emails, zooms and Microsoft Teams with a frequency not seen in pre-pandemic times. Suddenly, we can find our tribe anywhere around the world, not just in our backyard, and connecting with them is easy and no longer ‘unusual’ practice. Our circles of kin – of like-minded people who we connect with and care for – have flourished and reach all corners of the globe.

One such circle of kin expanded recently, when Hesham and Nicki, introduced as speakers at this year’s global Gathering for Kindness, reached into one another’s living rooms to further develop their growing sense of kinship. Hesham, in a United Kingdom autumn, was at the end of the day of putting his children to bed; Nicki, in a New Zealand spring was seeing a new day break and about to start the hustle of getting children off to school. We talked about wide ranging topics related to kindness such as the practice of gratitude; how we approach themes of mortality and life in discussions with our children; the ever-present threat of compassion fatigue and burnout in our current working environments in healthcare; moving from deficits-based to assets-based language and mindsets at individual and organisational levels, amongst other such ponderings. One of the ideas we spent the most amount of time discussing is how kindness can be used as a tool to replenish our own minds and hearts and simultaneously be doing the same for others around us, in the act of choosing to find ways to help those around us flourish and elevate themselves beyond ‘baseline’. We give, and receive, give, and receive, in a spiral with a potentially limitless upwards trajectory and in turn it bumps other people around us onto new upwards trajectories as well.

Critics of kindness are quick to say that’s all this talk of kindness is, words and niceties. We have more important things to focus on. Patient safety, staff shortages, burnout and resource shortages. Advocates of kindness will tell you that kindness deserves to be identified as a key tenet of any quality improvement system in healthcare, for its ability to have a positive impact on all of these difficulties and more. We are all somewhere on the optimist-cynical continuum of kindness, perhaps at different places on the continuum on any given day, and that’s okay. But what if we can find real life demonstrable examples of the ability for kindness to travel through people and systems far beyond what the eye can see, and the heart can feel?

That’s where innovations such as Hesham’s and his colleague John Lodge’s creation, Hexitime, have so much to show us about the mechanics of kindness and how much power it can yield in reaching out and lifting people around us up.

Hesham occasionally receives requests for coaching or mentoring from junior colleagues looking for self-development or considering a senior leadership role within the NHS. Since joining Oxford University Hospitals as Head of Integrated Quality Improvement those have come more frequently. One such request came from a trainee surgeon who was considering her next step on the career ladder. Despite being new in his post and stretched for time he agreed, and they had a rich discussion about her hopes and ambitions as he posed questions, offered advice and made further introductions.

At the end of the hour, she thanked him for my time and asked, “Is there anything I can do for you?”

He hesitated. There were so many things he could ask of her. She was talented, thoughtful, and enthusiastic and there were dozens of quality improvement projects he was trying to get off the ground. The opportunity to gain direct benefit was there, and she was technically in his debt. Weren’t that how things were done in places like this? Trading favours and building fiefdoms?

“No, thank you.” He replied. “But what I would like you to do, is to retrospectively take up my coaching offer on Hexitime, give me one credit then put an offer on there to earn one yourself.”

Confused, she asked why. He explained that as Hexitime worked as a timebank, and he would rather she pay that debt forwards to someone who could benefit from her talent and thereby extend the chain of kindness. Else, what develops is a clique of those more and more privileged- typically, disproportionately white, male and privately educated. But as an outsider himself, he was more interested in supporting outsiders to climb the snowy white peaks of the NHS, and he hoped she could join him in lifting as she climbed. She agreed, and Hesham thought no more of it.

What he didn’t expect is what happened next.

A few weeks later, at a regular meeting with the Hexitime co-founder John Lodge, he described enthusiastically how he himself had been the beneficiary of a Hexitime exchange with an individual who had offered some advice that might help us grow the site. As he spoke, Hesham recognised from the description that she was the same trainee I had met.

Although he had always believed that helping others is the right thing to do, what this demonstrated is that the waves of our generosity eventually come back to us- a form of universal karma. This is most evident in tight groups- families, clubs, and neighbourhoods. But across societies and communities, these ripples quickly become invisible. And when it exceeds the horizon of our awareness, that connection between action and impact is invisible. It is why helping a stranger is seen as a selfless act and giving charity is the exception, not the norm.

What was unusual was that this chain was so short with only three links back to its origin, whereas most often in communities and networks the chain extends outwards beyond the physical and temporal horizons. When someone lets you into a queue of slow-moving traffic, for example, you are more likely to do the same at a later junction, but that first individual may never see the impact of his or her act of kindness. It is that lack of foresight that leads to short-term gains for long-term societal losses.

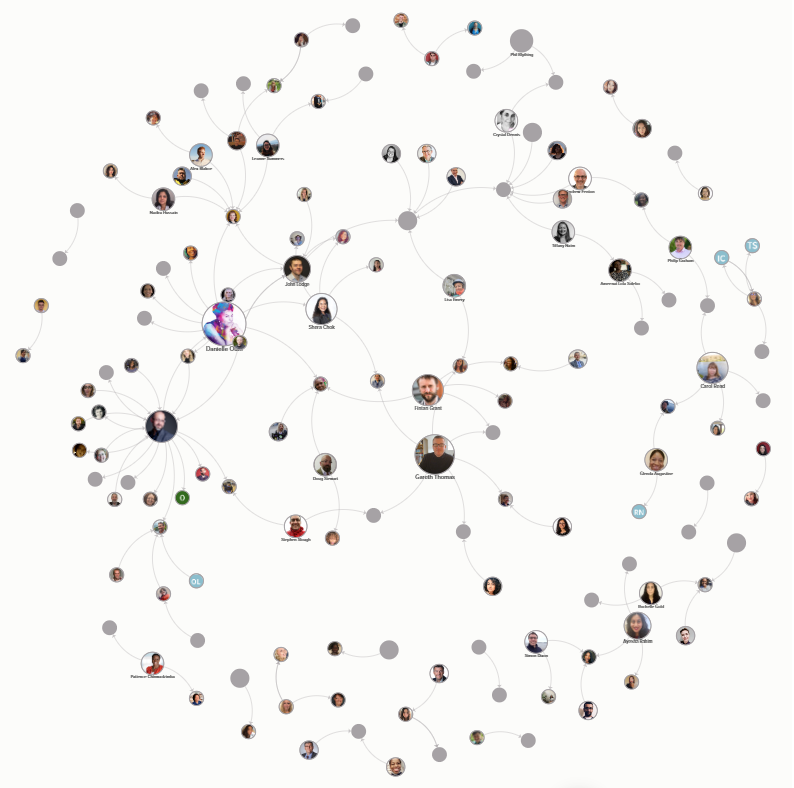

At Hexitime we can now map the chains of exchanges, like this one of exchanges between members and allies of the Shuri Network- a wonderful community whose purpose is to support Women of Colour in Digital Health- it offers a helicopter view through time and space of exchanges, so individuals can see their place in the chains of kindness. What is remarkable about this perspective, is that it becomes impossible to see where kindness starts and where it ends. The sequence of help and being helped travel like a circuit through electrical wires. In effect, we are all conduits for the transmission of that energy. We do not own the actions any more than a radiant heater can say it owns the heat that emanates from it. With this deeper understanding comes a greater readiness to give and to receive, through the realisation that kindness is not a well, but a limitless stream that flows endlessly.

By making visible the invisible in this way, we hope that in time, Hexitime will contribute to a workplace culture in which gifting of time is commonplace because when you give you ultimately receive. Where appointment to every senior role comes with an expectation that some of that time will be spent developing others, with no favouritism or intention of currying favours. When offering your time to strangers is seen as a wise investment, with a confidence that this generosity will be recouped in ways you may never know but you will benefit from.

- To participate in Hexitime, you can register here.

- The Gathering of Kindness runs up to World Kindness Day 2022, from 7th November to 11th You can get tickets here.

Nicki Macklin

Nicki Macklin is a PhD Candidate at the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, exploring how we can use intelligent kindness to support healthcare systems, and the people within them, to flourish. She is a Fellow of the Patient Revolution and is passionate about patient advocacy. Twitter: @nicki_macklin

Hesham Abdalla

Hesham Abdalla is a consultant paediatrician and Head of Integrated Quality Improvement at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. He co-founded Hexitime, the first timebank for sharing professional skills in healthcare. Twitter: @hesham_abdalla

Declaration of interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.