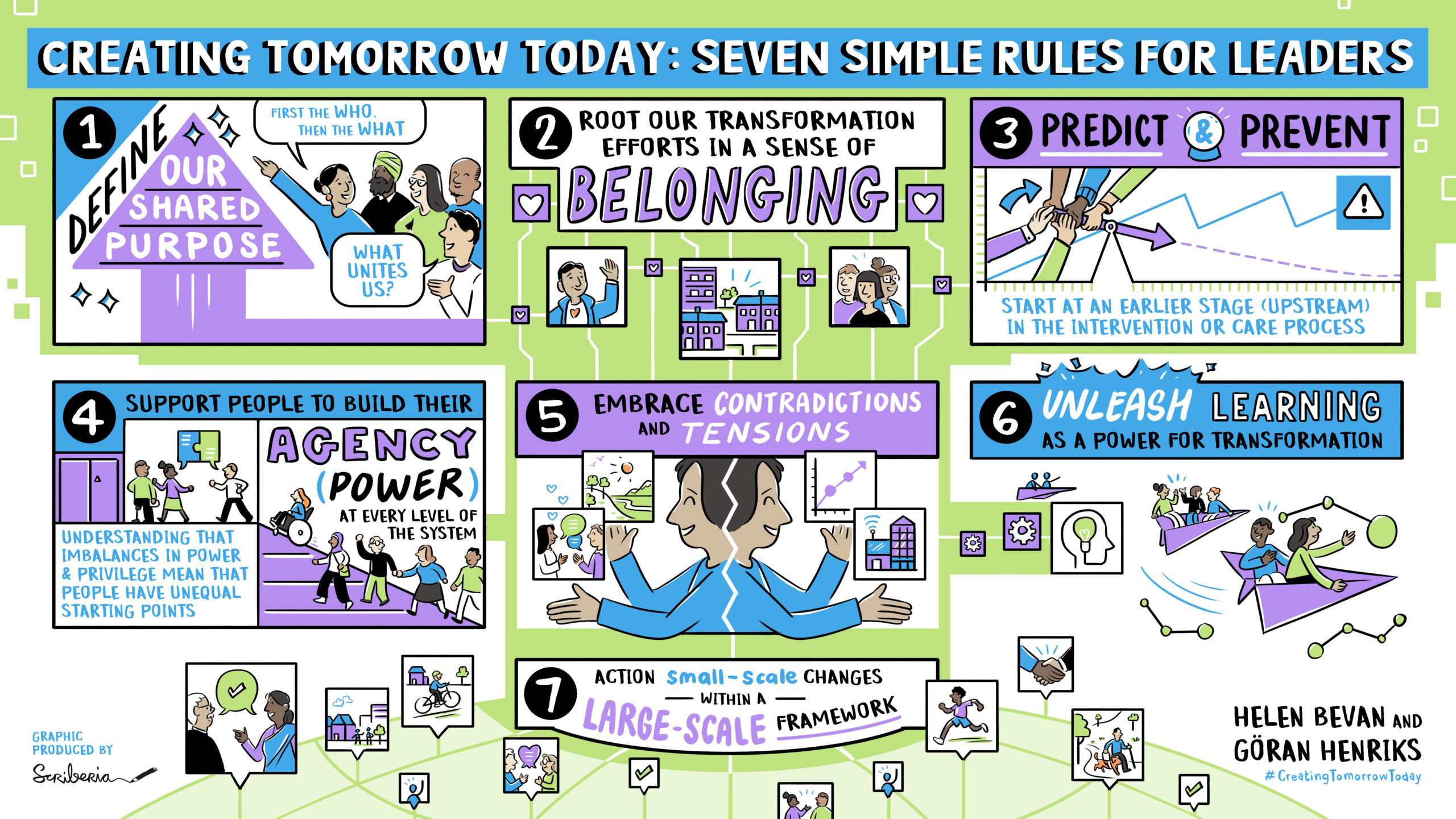

We have created a set of “seven simple rules” for leaders who want to create tomorrow today, based on our collective learning over seven decades as leaders and internal change agents in the health and care systems in England and Sweden and the work we have done with leaders in health and care in many other countries.

This is the fifth of eight blogs that we will be posting on BMJ Leader over the coming months.

Read blog one: our approach to creating the simple rules.

Read blog two: Define our shared purpose here

Read blog three: Root our transformation efforts in a sense of belonging

Read blog four: Predict and prevent: start at an earlier stage (“upstream”) in the intervention or care process

Rule no. 4: Support people to build their agency at every level of the system

When a person who lives with a chronic health condition feels that they are an equal partner with health professionals in decisions about their own health, that’s agency. When a frontline clinical team believes that they have the power to test improvements in their own setting without having to get permission or go through a bureaucratic process to proceed, that’s agency. We define agency as “the power and ability to make choices and act on them freely”. We differentiate between:

- Individual agency: People get more power and control in their own lives: through organisational status or credibility, activation, shared decision-making and/or self-care

- Collective agency: People act together, united by a common purpose, harnessing the power and influence of the group and building mutual trust

Agency enables people to make a positive difference and achieve their goals. It is about pushing the boundaries of what is possible, mobilising others, making improvements happen more quickly and sustaining change. Over the 70+ years that we’ve collectively been leading health and care improvement in large, complex systems, we have learnt a truth that is rarely discussed in leadership circles: change efforts are far more likely to fail because of lack of agency, than because of lack of improvement skills or resources or methodology. Of course, we need skills, resources and methods for change. At the same time, we understand that agency is the fuel that creates the energy for continuous, sustainable improvement.

If as leaders we want to create tomorrow today, we need to develop and support the conditions where people at every level of the system can build their own agency for improvement, individually and collectively.

Note the language here. Our simple rule says to “support people to build their own agency”. It does not say to “empower people”. There is an important difference. Empowerment is problematic because it starts with the premise that one who empowers has the power to begin with and grants it to others, on their terms. In a hierarchical system, that leader, or others who follow them in the role, can take the power back. “Empowerment” too often reinforces the imbalance of power and control in organisations and in improvement initiatives, rather than cedes power. Some organisations have banned the term “empowerment”.

“One of the most dangerous words we use is “empower”. Usually used to describe those typically underseen and underserved. “They” need us to empower “us”. “Empower” then keeps one above, one below. It’s how the status quo perpetrates.”

So “empowering” typically means giving people opportunities within the remit or confines of what the leader wants the people to do. Building agency is supporting people towards self-leadership, creating a sense of direction, making the choices they want to make, with the ability to act on them freely.

Agency is a key building block in our “seven simple rules”. When we combine it with other key components we described previously, like building shared purpose and belonging, and predicting and preventing, it is possible to the conditions for positive change on a very large scale.

The unleashing of agency during the pandemic

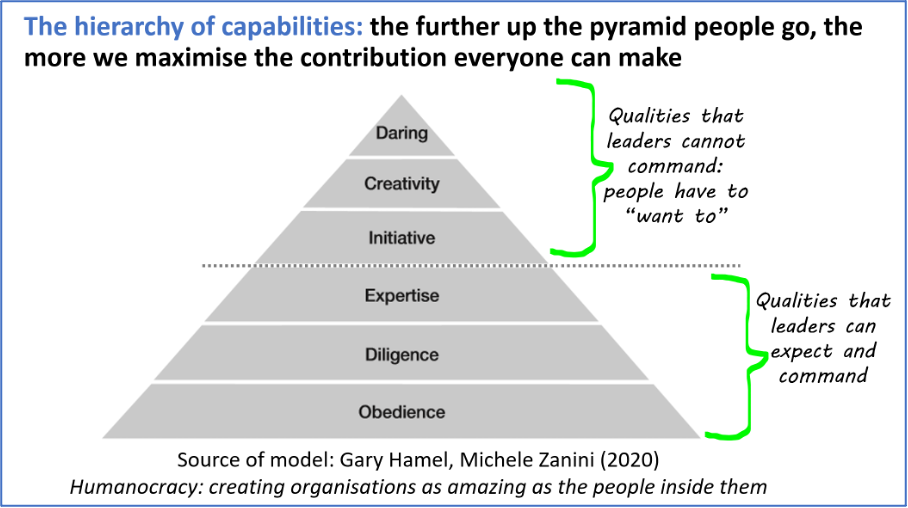

Across the globe, we witnessed an unprecedented unleashing of agency by people working in health and care as a response to the challenges of the pandemic. Rapid change was needed and many of the old rules and perceived risk factors were swept out of the way as people moved to action very quickly. This model of capabilities of people in organisations from Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini helps explain what happened.

Organisational leaders can expect certain things from the people in their teams. Starting at the bottom of the hierarchy, they can expect people to follow the rules, policies, quality standards and prescribed clinical pathways. They can reasonably expect people to be diligent and apply themselves at work. They can also expect people to have or develop the professional expertise needed for the job.

The capabilities at the higher levels of the pyramid are those we see in high performing teams and organisations. They include the ability to take initiative, to think differently and come up with creative solutions to problems and finally, the daring and courage to do things differently. Leaders cannot “command” people in these higher level capabilities. People have to want to develop and use them. They require leaders to support people to build their agency, the sense that they can take initiative and try new things without risk of punishment, criticism or ridicule.

In a pre-Covid 19 world, many people working in health and care operated with the capabilities in the lower part of the pyramid. When the pandemic struck, people had to use initiative. Clinical teams came up with creative solutions and worked with courage, outside of their comfort zones. Their leaders supported them to build their agency in this way. Far more people were working at the top of the pyramid with both individual and collective agency, with the courage that comes from a profound sense of shared purpose, driven by the needs of their patients many of whom were very sick. A key challenge in a post-pandemic world is how we retain and grow this agency and don’t return to just the capabilities in the bottom layers of the pyramid.

Learning about agency from an experience in the international development sector

A case study within the international development sector, from a research article titled “Cross sector partnerships as capitalism’s new development agents: reconceiving impact as empowerment” by Anne Vestergaard, Luisa Murphy, Mette Morsing and Thilde Langevang, provides some important lessons about helping people to build their agency.

The article tells the story of a partnership between:

- a non-governmental organisation (NGO) based in Ghana with a mission of alleviating poverty

- a Danish company that manufactured and sold bead jewellery made from recycled crushed glass.

On a visit to eastern Ghana, the owner of the jewellery business saw enormous amounts of brightly coloured beads made from recycled glass at a weekly bead market. She recognised the potential to apply her knowledge about glass to start a jewellery making business in the area, which made the glass according to Ghanaian tradition but assembled them based on her own designs to sell to North American and European markets. Witnessing the challenging living conditions of women in the area, she also saw the possibility of helping local women by employing them to produce and assemble the beads. The Ghanaian NGO could also see the potential to realise its social mission to employ and train single mothers to become financially independent.

They set up a “Business-NGO partnership” aimed at alleviating poverty in villages in Eastern Ghana, with a worthy goal to break the poverty cycle through education and alternative livelihood opportunities.

The partnership was set up in a way, which although very well intentioned, was based on an incongruence, which meant its goal was very hard to reach or could never be achieved. Although the authors of the article don’t use this language, what they describe is that the mindset of the partnership was “empowerment” (on the terms of the business and its owner), not building the individual and collective agency of the women (which is about increasing their capacity to make their own choices and act on them).

“Competences without agency”

The bead partnership was seen as a success from the perspective of the NGO because it delivered on its promise in terms of providing resources and competences for the women it employed. However, the authors conclude that from the perspective of the women in the villages, there was little, if any, benefit from the partnership.

Here are six reasons why this “empowerment” approach didn’t build agency:

- Lack of co-production and power sharing: The women who made and assembled the beads were not set up as partners and were not included in the decision-making processes. They were taken on as contract workers, without any form of employment contract, social security or protection.

- Hand-picking of employees: the bead partnership only recruited those with existing skills and aptitude, so chose those that were already best placed to create a different future for themselves.

- Unstable employment: Work was only available to the women when there was a demand from the jewellery producer’s markets. Overall, there are 3-4 months every year without income from the partnership and income was unpredictable.

- Having to travel to work: To reduce the risk that materials might “disappear”, as well as to ease quality assurance processes, assemblers were required to travel to an office to work rather than work from their homes. This meant the women could not share the work with family and neighbours as would traditionally be done so skill transfer was rendered impossible.

- Specialist nature of the skills: Although the jewellery production was based on traditional techniques, the designs were those owned by the jewellery company for a Western market. The women were not able to take the skills or designs they learnt and apply them as part of an independent production. There were no instances of employees subsequently establishing themselves in the jewellery business or otherwise become self-sustaining through entrepreneurship, beyond what some of the bead producers were already doing. There was no transfer of skills from the partnership to the communities.

- Lack of voice and inflated expectations: There were issues of great importance to the women upon which they had no influence, such as the problem of transportation costs, unstable income and lack of health insurance. Although they tried, the women did not manage to have these concerns met. Within their own villages, some of the women got greater voice because they were working for a perceived high-status white business. However, other villagers thought that the employed women must have more income than they actually did, and these perceptions led to requests to borrow money and tensions in community relationships

In effect, the resources and competences, which the women acquired through the bead partnership (income, technical skills and new knowledge), did not help them to build their agency. It did not provide the women with better opportunities to live the lives they desired.

The bead partnership resulted in what the authors label “competences without agency”. It provided new resources and knowledge to the women but failed to generate the conditions for these to be transformed into significant changes in their lives. Because the bead partnership failed to give primacy to the higher-level goal of alleviating poverty, the competences with which the women developed were siloed into the partnership, reducing their potential to be transformed into means with which the women and the communities of which they were part could pursue their own goals. The women were provided with health education, but without access to health services. They were provided with technical skills, but without being able to use them for their own production. They were provided with an income but without this being adequate for self-sufficiency. Having to make themselves available for whenever the partnership offered work, acted as a barrier to pursuing other opportunities, which might have provided self-sufficiency. Essentially, the women had very little control over the resources and competences they acquired through the bead partnership, which critically constrained their ability to put them to use in pursuit of their own goals.

How is this relevant to our health and care context?

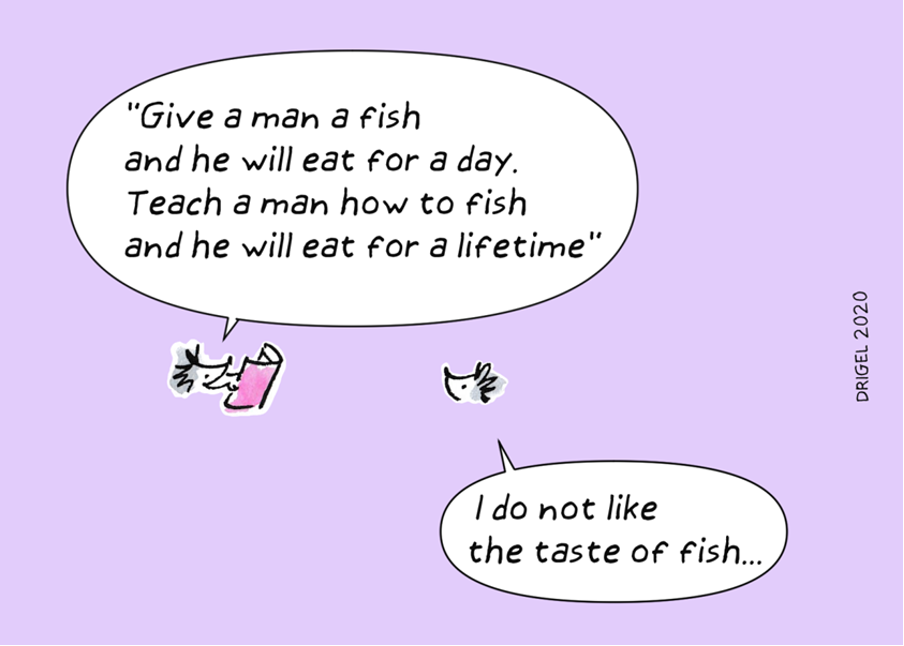

Agency is a critical bridge between giving people resources/capabilities for improvement and the achievement of improvement goals. Giving people skills and resources may not be enough if we don’t create a context where people can act on them. So, the villagers in the story above learnt new skills but they didn’t get the power through agency to use these skills to make a difference in their lives. Relating this to the “hierarchy of capabilities”, earlier in this piece, the women got capabilities related to following the rules and processes, diligence and expertise at the lower part of the pyramid, but they couldn’t build the agency necessary for initiative, creativity and daring and achieving their personal goals.

We see the equivalent situation to this happening frequently in the world of health and care improvement. Very often, leaders of organisations that are committed to an improvement approach focus on methodology and technical skills for improvement without considering the need for agency. This can have unintended consequences. An example is the feedback that many of the change activists participating in the School for Change Agents gave in 2019. The people who join the school are the kind of motivated, active people that we would want to see leading improvement efforts in our organisations. However, many reported that their organisation’s improvement methodology was a barrier, not an enabler of change. They viewed it as disempowering because it was imposed on them in a top down, controlling way. It was experienced as the opposite of agency. To quote Chris Argyris, from Flawed advice and the management trap:

The essential flaw of [improvement methodology] is that, when implemented, it tends to reinforce the mechanistic and hierarchical models that are consistent with the mental maps of most managers

Those leading improvement need skills and resources for improvement but unless we can link it to our own agency and enable people to be part of daily problem solving and decision making (making changes to things that matter to them), the training and resources may not be of use.

Source of graphic: Lionel Francois

How can we build agency within our systems and organisations?

Many of the organisations that are promoted as case studies in agency at work are teams like Buurtzog, (the organisation that revolutionised community care in the Netherlands with its model of holistic care) that were set up as “self-managing organisations” from their inception. The Buurtzorg model starts from the client perspective and works outwards to assemble solutions that bring independence and improved quality of life. It is based on universal human values that the clients receiving services want control over their own lives for as long as possible. The professional attunes to the client and their context, taking into account the living environment, the people around the client, a partner or relative at home, and on into the client’s informal network; their friends, family, neighbours and clubs as well as professionals already known to the client in their formal network. In this way the professional seeks to cocreate a solution involving the client and their formal and informal networks. Self-management, continuity, building trusting relationships, and building networks in the neighbourhood are all important and logical principles for the teams.

Leaders do not need to “empower” others in Buurtzog: everyone is fully vested with power by the very design of such an organisation. The power is not delegated but fully distributed, enabling teams to make their own decisions, based on the needs of the people they serve, without having to check back with leaders. The organisation does not fall to pieces without leadership control; quality and safety are not compromised and Buurtzog continues to achieve outstanding outcomes at lower cost.

Building cross-organisational agency within an existing system with established structures and mindsets can be much trickier. It’s worth looking at the resources on Gary Hamel’s “Humanocracy” website. In particular, you might want to carry out a Bureaucracy Mass Index (BMI) assessment or organise a “Management Hackathon” with your leadership team.

Finally, we are not talking about agency for the sake of agency; agency isn’t the goal – the goal is the goal. It is about understanding that agency is a fuel that moves us towards our bigger purpose. It is when, in an organisational context, we combine agency and capability as part of a wider learning system or quality management system that we create the conditions for change at scale.

How can we build our own agency?

Many people who are reading this piece work in organisations or systems that feel top down and bureaucratic. If you have to wait for organisational leaders to create the conditions for agency, it might be a very long wait. So, what actions can you take to build your own agency for change and that of your team?

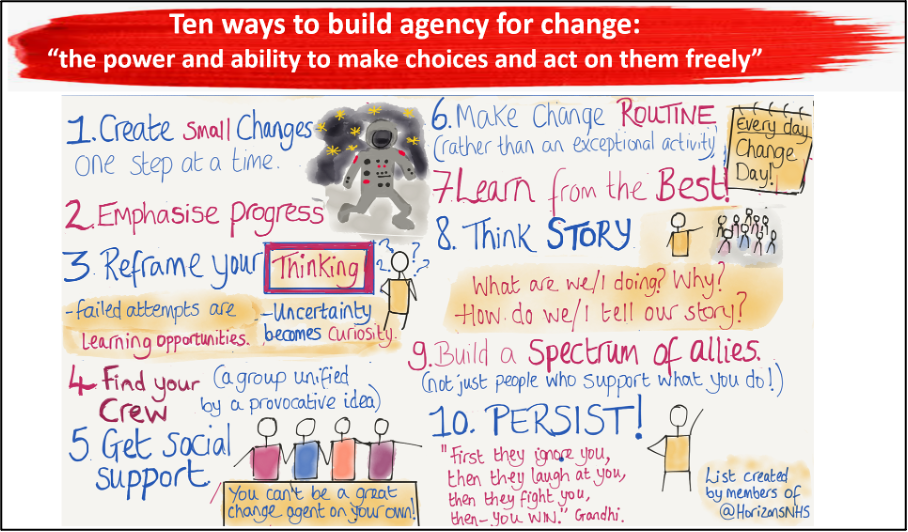

Here are ten suggestions:

Source: the NHS Horizons team, drawn by Leigh Kendall

- Create small changes for improvement on a continuous basis: We often underestimate the power of small changes. Testing a change, even on a very small scale moves us from concept to action and creates a sense of possibility, hope and confidence, as well as new knowledge for improvement.

- Emphasise progress: People in professional roles report that their best days at work are when they make progress and are able to move forward in their work. Create those conditions for and within your team.

- Reframe your thinking: Rather than labelling something that didn’t work as a failure, reframe it as a learning opportunity; think of yourself as an explorer rather than an expert, so that uncertainty becomes curiosity.

- Find your crew (a group unified by a provocative idea): Join the School for Change Agents, a free online community and learning programme, involving thousands of people who are taking their own power for change.

- Get social support: Change and transformation is inherently relational: it depends on our ability to work with others to make change happen. Building collective agency also helps us see beyond individual changes to systems improvement.

- Make change routine: Organisations and systems that have a well-developed approach to quality improvement, or a quality management system, create the best of both worlds: a systemic approach to improvement that enables agency for change. Embrace the opportunities this gives you if your organisation has this.

- Learn from the best: social media can give us agency. It enables us to reach out and connect with others, breaking down the barriers of hierarchy. So, identify the people who are the best in the world at whatever you are seeking to do and reach out to them through social media. The worst thing that can happen is that they say “no” or ignore you. There’s a high possibility that they will respond and help.

- Think story: Story telling is one of the most effective methods for building collective agency. When other people hear our stories, they connect at the level of values which is the most powerful levels to connect at for mobilising for collective action.

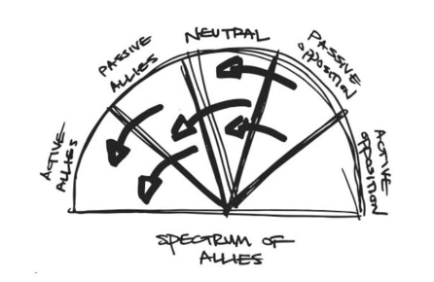

- Build a spectrum of allies: Too often, we build alliances for change with other people who already think like us and/or already have the same goals for change. This creates an “echo chamber” effect, making it difficult to spread change and to build collective agency on a scale where it can make a difference. Use the “spectrum of allies” methodology to think about ways to shift people along the spectrum from active opponents to active allies and build collective agency with a much greater group of people.

The spectrum of allies: art Josh Kahn

- Persist: Following actions 1-9 above will help you to build your individual and collective agency and give you the confidence and support to keep going. It has a generative effect; the more you persist, testing and making changes, showing progress and building support, the more your agency will grow

Key questions to reflect on in blog five:

- What does “agency” mean in my own context?

- How lessons can we take about building agency in our own system from the case study about the bead partnership?

- To what extent are we building individual and collective agency as an explicit part of our own improvement efforts?

- What actions can we take to build agency for change?

Please join in the conversation on Twitter, adding #CreatingTomorrowToday and @BMJLeader to your tweets.

Helen Bevan

Helen Bevan @HelenBevan is a leader and facilitator of large scale change in health and care. She is a Strategic Advisor with the NHS Horizons team, England.

Göran Henriks

Göran Henriks @GoranHenriks is Chief Executive of Learning and Innovation with Region Jönköping County, Sweden.

Declaration of interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.