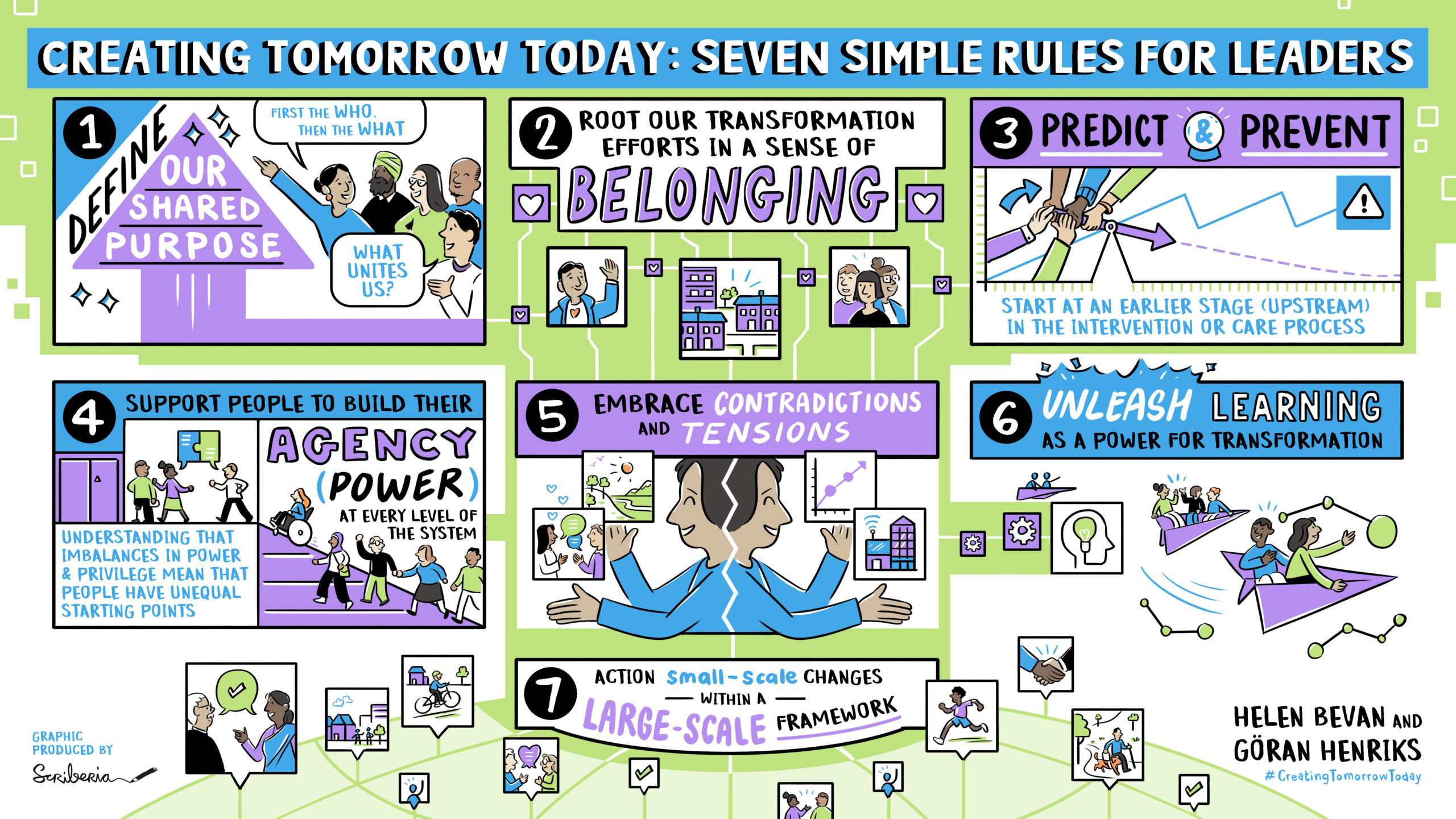

We have created a set of “seven simple rules” for leaders who want to create tomorrow today, based on our collective learning over seven decades as leaders and internal change agents in the health and care systems in England and Sweden and the work we have done with leaders in health and care in many other countries.

This is the fourth of eight blogs that we will be posting on BMJ Leader over the coming months.

Read blog one: our approach to creating the simple rules.

Read blog two: Define our shared purpose here

Read blog three: Root our transformation efforts in a sense of belonging

Rule no. 3: Predict and prevent – start at an earlier stage (“upstream”) in the intervention or care process

“No one can see the future, but we must try.”

The concepts of focusing upstream, prediction and prevention are key principles for strengthening the value of work to improve health and care. Here is how we define them:

Focusing upstream means identifying what we could do earlier in a care process or other form of value-adding process, or in someone’s life to prevent problems from happening and get better outcomes

Prediction means using data in all its forms and/or hypothesis to forecast risk or likelihood so we can act upstream to get better outcomes downstream.

Prevention helps us to focus upstream on the steps ahead or before us in a value process, enabling us to optimise health and increase the likelihood of things going right, rather than wrong.

Discussions about “upstream” in health and care are most often macro level considerations of the health of a population and addressing the causes and impact of differences in health status between groups that are avoidable and unfair. This “upstream” approach to health inequity is shown in the graphic below from Brian Castrucci. The pandemic shone a light on these issues and demonstrated even more strongly the link between health inequality, upstream community conditions and severity of disease.

Source of image: Brian Castrucci, Health Affairs

We want to suggest that these principles of prediction, prevention and upstream are also highly relevant to the daily work of improvement in teams and organisations, at a micro level.

In our three decades of leading quality and safety work in health and care, the most common question we see improvers addressing is “how we can refine the way we work so that our improvements “sit” within the conditions we operate within (daytime, on-call time, seasonal variation, etc.)”? Too often, healthcare improvement work is a reaction to negative performance or to downstream actions. As improvers, we focus our efforts on reducing waiting times or redesigning treatment pathways at a downstream place in the journey of care. We aren’t saying that these improvement activities lack importance. What we are saying is that we end up building on and trying to fix the existing process or system without thinking about prevention or prediction upstream.

In his book Upstream: the quest to solve problems before they happen, Dan Heath tells a story about two people sat fishing on a riverbank. Suddenly a child appears in the water in front of them and is struggling. One of them jumps in and pulls the child out. Then, minutes later, another child comes down the river, so they jump back in and pull out the child. And this keeps happening. After a little while, they’re getting exhausted after pulling children out. So, one of them starts walking back up the river. The other shouts to ask why and gets the reply “I’m going to go and find the person who’s throwing these kids in the river”. This is a powerful analogy for much of our improvement work in health and care. We are busy with the improvement equivalent of saving the kids in the river without actually going and finding out who is throwing them in in the first place.

Dan Heath sets out three main barriers to upstream thinking:

- Problem blindness — We cannot solve a problem when we don’t perceive it as a problem. Often in health and care, the problems are so ubiquitous, we accept them as being part of the context we work in.

- Tunneling — “In a tunnel, there’s only one direction to go, assuming you don’t want to go backward: You just have to make your way forward.” When we’re focused on solving immediate problems all day, it’s hard to take a step back and embrace a systemic outlook.

- Lack of ownership — The more complex and diffuse a process is, the less likely it is to have a clear line of ownership. When no one owns an upstream problem, it probably won’t get solved

A consequence of these barriers in health and care (our equivalent of the kids in the river) is widespread failure demand. John Seddon describes failure demand as “the demand placed on the system, not as a result of delivering value to the ‘customer’, but due to failings within the system”. When we don’t have a preventative mindset, we can end up dealing repeatedly with the same problems downstream, sometimes without actually effecting improvements in people’s health. Examples of failure demand include treating a person for health issues without considering their wider life context, high volume care processes driven by the need to hit a waiting time target without thinking about co-morbidities or inequalities, multiple appointments for care, hospital admissions and readmission. Without a focus on prevention in this wider sense, it’s unlikely that services will be redesigned in ways that avoid service-users making repeated use of the service and avoid service-givers having to deal with the same problems repeatedly.

Continuously improving with an upstream mindset means building in learning systems across care processes and communities, (upstream AND downstream). We need to work with a spirit of experimentation in our daily activities: try something, see what happens and improve on it that links back to finding new ways to achieve shared purpose. These practices can help those of us leading improvement to stay ahead and think more in terms of risks and mitigation. They may take longer and involve more people than in small scale improvement work, but the results are likely to be more impactful.

These concepts of upstream, prediction and prevention challenge our daily actions, and skillsets. They help us create the mindset to work with our own imagination. Our daily work gets energy when we have the space to become more innovative and to keep learning and improving.

Case study 1: prediction and prevention

Jönköping County Region: predict and prevent hospitalisation for Covid

At the early stages of the pandemic, many people in high-risk groups in Jönköping County Region only contacted the health system when they were seriously ill with Covid-19 and often went direct from the emergency room to the Intensive care unit. Against this background, Region Jönköping County created a new process that can be described as upstream working, using the change concepts of prediction and prevention.

When a person in an at-risk category shows a positive test result for covid, the local health care center they are registered with is alerted. This includes older people, those with diabetes, those who are overweight or who have lung diseases. The centre team supports the person in their own home until the person is healthy again. This includes the use of home oximetry and someone from the centre team calling them for a specific number of days after a positive diagnosis.

Across Jönköping region, 44 care centres were supporting a total of 135-220 patients every day in this way. Many of patients had not planned to go to the doctor or the hospital and often had not realised how much they were at risk.

The procedure may have saved many patients says the CEO of Primary Care Lotta Larsdotter. Now, the minority of people who need to come to the hospital do so in time and the risk of them becoming an intensive care unit patient is reduced. “Many patients and relatives are very grateful”.

Case study 2: Predict and Prevent at the Southcentral Foundation

The Southcentral Foundation is an Alaska native-owned, nonprofit health care organisation serving 65,000 Alaska Native and American Indian people. The foundation has operated a unique system of care, Nuka, based on predict and prevent principles for over 20 years. The Southcentral Foundation is a fully tribally owned and managed health care system so the people that it serves are not patients but “customer-owners”, not just of services but their own healthcare journey. The entire system is based on delivering services when, where, and how the customer-owner wants.

Primary Care is provided by teams of people with expertise in physical, mental, and emotional health. Customer-owners are guaranteed same day access to the same people who know their story and know them by name. The Integrated Care Team includes primary care provider, behaviorist, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, and midwife. Since the Nuka system was introduced, clinical indicators have moved from low to the top quartile with decreased costs and outstanding satisfaction and workforce retention.

Specialty and complex care are piggybacked onto the Primary Care generalist team. Co-located in Primary Care are specialist experts in pain, HIV, psychiatry, addictions, physiotherapy, adults with complex needs, and children with complex needs. An example of how this works is that there is one HIV expert making sure that the many hundreds of HIV positive individuals each get perfectly targeted care and medication – delivered through the generalist primary care team – with expert support from the HIV specialist. There are no special HIV clinics and no special HIV days – and everyone is included in the numbers. Results are that 96% of people living with HIV are actively engaged in medical care (US national average 65%), receiving the ‘perfect’ drug regimen and 91% have no detectable virus (US national average 56%) – without the stigma of being identified in any way by where they go or who they see.

Reference: Doug Eby, Vice President of Medical Services, Southcentral Foundation

Case study 3: Predicting which patients will need help with virtual visits and preventing difficulties in access to consultation visits

The almost overnight shift to virtual consultations as a result of the pandemic has meant that across the globe, many patients have had to get to grips with digital systems to access care and there was a lot of pressure on IT support, clinical support and/or front desk teams to manage new systems at scale.

At Johns Hopkins Medicine in the USA, a process was established whereby a member the support team had to ring each patient just before their video visit to make sure they were able to access the call. This was a high-volume task and from talking to patients, the team realised that not every patient needed this pre-call. So the team developed a “video visit technical risk score” tool in their electronic health record (EHR) system to identify patients who would require technical assistance prior to their visits. It was based on the extent to which the person was or wasn’t using their EHR, whether they had checked in for the appointment online and if they had had a previous virtual appointment. As a result, only those who were deemed “high risk” were called in advance and it became a more targeted, personalised process. Feedback from the team suggests it is also a more efficient process.

Case study 4: Using innovation to reduce the number of children not brought for hospital appointments

Ten specialist children’s services in England are participating in a shared two-year programme, hosted by the Innovation Group at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, using Artificial Intelligence to identify children and young people at the greatest risk of not being brought for appointments, and then support targeted interventions by the ten organisations to engage with those patients.

In the ten organisations, more than 9% of scheduled appointments were in the “was not brought” (WNB) category in the year before the pandemic. This represents a significant health risk for many children and young people and it also meant resources are not used as well as they could be.

It is still early days, but currently, the AI predictor tool is showing a success rate of 80% of identifying children and young people at risk of not being brought. The organisations have set a target of maintaining at least this level of success for all the systems the tool is introduced to, and then using it to reduce the number of WNB patients by 25-50%. The programme will specifically evaluate the impact on reducing WNB in deprived communities and other groups that are impacted by inequalities.

Focus on what goes right, not just what goes wrong

The principles of predict and prevent demonstrated in the case studies have been practiced in other sectors over many years. In his book “Resilience Engineering in Practice”, Erik Hollnagel reminds us of how important it is to think positively, seeing what is working, not only what is not working. He says that in our efforts to improve safety in health and care, we are often caught in processes that deal with errors or failures. He says we need a different mindset. Instead of being focused on this idea of avoiding treating failures as unique, individual events, we should see them rather as an expression of everyday performance variability. Excluding exceptional activities, it is a safe idea that something that goes wrong will have gone right many times before—and will go right many times again in the future. Understanding how acceptable outcomes occur is the necessary basis for understanding how adverse outcomes happen. In other words, when something goes wrong, we should begin by understanding how it (otherwise) usually goes right, instead of searching for specific causes that only explain the failure. Adverse outcomes are more often due to combinations of known performance variability that usually can be seen as irrelevant for safety, than to distinct failures and malfunctions.

In consequence of this, the definition of safety should be changed from ‘avoiding that something goes wrong’ (what Hollnagel calls “Safety I thinking”) to ‘ensuring that everything goes right’ (“Safety II thinking”). Safety II is the system’s ability to function as required under varying conditions, so that the number of intended and acceptable outcomes (in other words, everyday activities) is as high as possible. The basis for improvement activities must therefore be an understanding of why things go right, which means an understanding of everyday activities. Working with predictions and clear improvement aims helps us to switch to a Safety II culture where people’s mindsets are focused on the positive examples. The predictions can become a calibration of the daily performance of the work.

Questions for upstream leaders seeking to predict and prevent

Dan Heath sets out seven questions for leaders who want to move upstream. We have interpreted them for our health and care context:

- How will you unite the right people? We need to surround the problem with the right people who collectively can see the big picture, as well as people who experience the care and those working at the point of care, in a process of co-production.

- How will you change the system? No part of the system exists in isolation. Changing any one part of the system will have knock-on consequences in other places. Consequently, the best upstream intervention is a well-designed holistic system underpinned by a sense of shared purpose amongst all those who play a part in the process.

- Where can you find a point of leverage? There are many potential points or places to intervene in a system. Those interventions that are about mindsets and ways of seeing the world are often of higher leverage than those that are about changing components or parts of a process.

- How will you get an early warning of the problem? How can we use data and insights from people in the system as part of a learning system approach?

- How will you know you’re succeeding? With upstream efforts, success is not always self-evident until much further downstream. We need a balanced set of measures to get the full picture.

- How will you avoid doing harm? Zoom out and pan from side to side. How does it affect the system as a whole? Can we create closed feedback loops so we can improve quickly?

- Who will pay for what does not happen? Many current payment systems reward and incentivise downstream activity. If we undertake less downstream activity (as a result of moving our focus upstream and preventing later harm or error), we may need to change the payment and reward systems.

Please join in the conversation on Twitter, adding #CreatingTomorrowToday and @BMJLeader to your tweets.

Helen Bevan

Helen Bevan @HelenBevanTweets is Chief Transformation Officer with the NHS Horizons team, England.

Göran Henriks

Göran Henriks @GoranHenriks is Chief Executive of Learning and Innovation with Region Jönköping County, Sweden.

Declaration of interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.