Art and the SDGs is a public engagement project between artisans from the Janakpur Women’s Development Centre (a centre of Mithila art and culture) in the southern plains of Nepal, researchers at UCL Institute for Global Health and the United Nations in Nepal to promote dialogue between students and artisans about local meanings of the SDGs. The project was paused due to COVID-19 and we spoke to artisans over the phone to explore how the pandemic was affecting them.

“The pandemic has left me overwhelmed with debt, I barely have anything to eat”, said Sita* over the crackly phone line from her mud-walled home in monsoon soaked Janakpur in the Southern plains of Nepal. She continued, “I eat one meal a day so that I can survive the next. It has been a tough time for me and my family.” Sita works with other female artisans from the Maithila ethno-linguistic group at the Janakpur Women’s Development Centre (JWDC). Maithili is second most widely spoken language in Nepal. Many of the artisans are marginalised by widowhood, caste, gender-based violence, and illiteracy. For them, JWDC is both a source of livelihood and a hub for cultivating community.

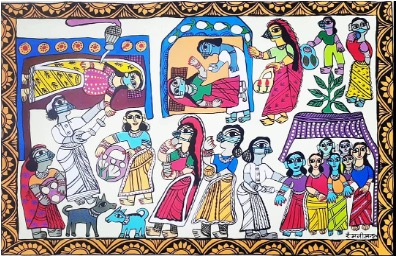

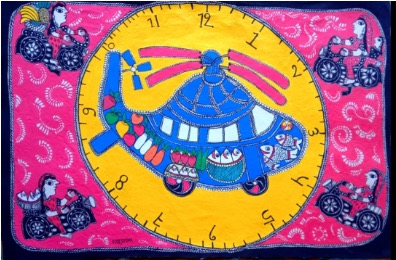

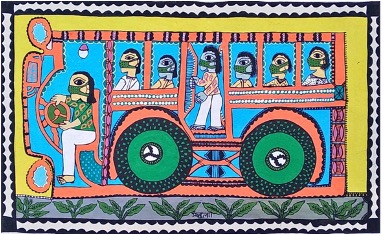

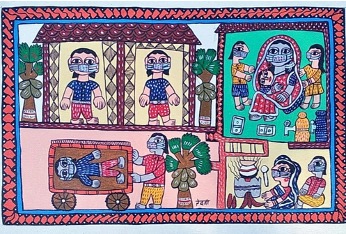

Traditionally, Mithila art depicts daily life, religious rituals, and cultural heritage, but JWDC artisans also address contemporary social issues, such as life during the pandemic. Their recent paintings tell stories of illness (Figure 1), mass testing (Figure 2), and social isolation (Figure 5), where faces are now covered with masks. The pandemic has had an impact in dimensions stretching beyond health.

Earlier this year, our project to explore local meanings of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through art was paused as a devastating wave of COVID-19 hit Nepal. By May 2021, newspapers were reporting oxygen shortages across the country. In this context, the Health SDG seemed a natural focus of our conversations when we called the artisans who had access to mobile phones. But they quickly moved on to discuss their immediate concern: the impact of the lockdown on their livelihood.

Although currently open, JWDC was closed for months because of a strict government lockdown. Artisans have sold some of their paintings and products online but the national restrictions – including closure of the airport for several months – have had an impact on their income as sales were largely dependent on tourism. An artisan said: “I am worried …now no tourists come to JWDC or to our country.” This loss of income combined with an increase in food prices increased financial pressure on artisans. According to the World Food Programme, the number of households in Nepal experiencing loss of income between December 2020 and June 2021 doubled from 21 to 45 percent. Some artisans have struggled to access food and meet their basic needs during the pandemic (Figure 3).

But the closure of the centre didn’t just have an economic impact. The artisans were used to spending their day at JWDC, but during lockdown they spent most of their time at home in houses which felt overcrowded with grandchildren trying to do schoolwork and newly returned migrant worker sons. Prior to the pandemic, nearly one third of Nepal’s economy was dependent on remittances from migrant workers. The pandemic led to thousands of migrant workers returning to Nepal (Figure 4). Some estimate that more than 500,000 people returned home. Artisans were happy to be reunited with family members, but worried that this was not sustainable. Bibha* said:

“It has been extremely difficult for me and my family. We have been facing financial problems. There are 9 people living in the same room. Our ceiling has been leaking because of the heavy rain, my grandchildren are not able to have a proper education, my office is shut down… thinking about of all of this makes me really sad and depressed.”

Artisans told us how their mental health and wellbeing had been affected, and how they missed a tight-knit community of friends (Figure 5). Most artisans do not have their own phones and had not been in contact with each other since the centre closed. They were also unable to regularly exercise during lockdown and missed their daily walk or cycle to work. Artisans became dependent on the income of husbands or sons:

“When I used to earn, I could spend my own money and was less dependent on my son…When I went to JWDC, my life was much better…. I am used to going out and working, not sitting at home.”

This experience corresponds with global evidence that COVID-19 has exacerbated gender inequalities, and highlights a need for social protection and a gender informed response to the pandemic.

Our discussions offer one of many narratives about the effect of the pandemic, and only reflect the experience of those with access to with mobile phones: the stories of those without also need to be heard. Our conversations made visible the interconnectedness of health and well-being to livelihoods, technology, tourism, and gender. As we re-start our project engaging communities about the SDGs, these conversations add emphasis to global calls for holistic approaches to meet the SDGs.

*Names in the blog changed to protect their identity.

About authors: Joanna Morrison, Senior Research Associate, UCL Institute for Global Health, London, UK

Sara Wong, Research Assistant, UCL Institute for Global Health, London, UK

Dollie Shah, Research Assistant, Janakpur Women’s Development Centre, Janakpur, Nepal

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Susie Vickery and the owners of the paintings. We would also like to thank Mr Satish Sah, Operations Manager at the JWDC, and the artisans of the JWDC. Art and the SDGs is funded by UCL Grand Challenges.

Competing Interests: None

Handling Editor: Neha Faruqui