By Anna Baverstock

Resilience has for many become an unmentionable word. It is also a ‘trigger’ word. Often generating an intensely negative reaction in some, that then negates anything that may be discussed after. My role as Associate Director of Medical Education (ADME) with responsibility for supporting junior doctors enables me to meet with many junior doctors and their educational supervisors. I have been increasingly interested in the debate that is ongoing around resilience.

Dan Magnus often reflects, even in a perfect system, with an awesome team and ideal balance of capacity and demand, we still need resilience. (Also see his blog on his fabulous website yougotthiswellness.com.) By the nature of our role we often face situations that are challenging. There is much we can do within our teams and systems to enhance this. So, what would it look like, if we concentrated on building resilience within our teams and how would we start?

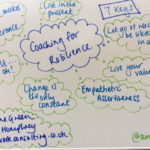

I have just finished the excellent Coaching for Resilience. Further in depth reading of Green and Humphrey’s practical book is recommended. Defining resilience as ‘the ability to bounce back’ they divide it into seven ‘keys’. Some resonated more with me than others, highlighting there is no one size fits all. Key One describes our need to be in control and to be liked. We often read and reflect that we are not very good at saying no, even when busy. This is often due to a strong desire to be liked and want to please. But we also have a strong desire to be in control. When overloaded our resilience is ‘stressed’.

Managing the volume of workload is further highlighted in key two. Describing the well known matrix popularised by Stephen Covey in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. We get drawn towards urgent tasks that are or are not important. Not enough planned time is spent in ‘important but not urgent’ and we often waste time in ‘not important and not urgent’. This often feels very unsatisfactory. Spending too much time firefighting and not enough in planning the more important aspects of our jobs, leaves little room for evaluation and improvement.

Key three discusses empathetic assertiveness ‘If you don’t have a plan for your life someone else does’ to quote Anthony Robbins. We need to facilitate further reflection on this. Much has been written about undermining and bullying behaviour and the widespread negative consequences. It can still be challenging to feel empowered to question behaviour if we feel unsupported, or our working in new unfamiliar teams.

Key four focuses on ‘change is the only constant’. Our reflex reaction is often to see any change as a danger or threat. With time and practice we can learn to see change more as an opportunity. But for many of us this will need time and revision! Describing the familiar stages of learning any new skill or technique, we start off ‘unconsciously incompetent’. When we make a start it feels clunky (consciously incompetent). As we become more skilled, we move towards ‘conscious competence’ where we still need to think about something and adapt but we become more proficient. Finally, we can set ‘cruise control’ as we enter ‘unconscious competence’.

Key five reflects that ‘life is difficult and that’s ok’. As serial high achievers many of us don’t have much previous experience of failure. We work in an environment where there are very mixed messages about what happens when things don’t go to plan. Much has been written, and is being discussed as to how to reestablish a learning, and not a blame culture in medicine. We need as educators to understand this and develop better systems for learning from system error. We need to move away from individual blame, as we all recognise the complexity of human and other factors within our teams.

Key 6 is harder to summarise here but describes how ‘attitude makes all the difference’. What we all think and believe and how we act are important. Exploring our thoughts, our inner dialogue and how we can adapt and learn from this.

The final key 7 talks about ‘living in the moment’. The mindfulness ‘epidemic’ certainly highlights the importance of this. We create most internal stress by ruminating over the past or worrying about the future. By remaining on ‘high alert’ we prevent ourselves from enjoying the moment or relaxing in between higher stress activities. On a busy shift there are opportunities to stop and take a few minutes to relax, but we often fail to take these. There are some lovely and creative solutions emerging on social media to take ‘mindful moments’ even on a busy ED shift.

Building resilience is not an exclusive answer to stress and distress at work. Much of my role has been looking at the wider system that junior doctors work in and how improving the work environment, supervision & support available. I am also interested in how we can start conversations around resilience. Both at an individual level and within teams, I do believe there is much we can do. We all have a role to facilitate taking breaks, giving and receiving feedback and enhancing team culture. Team dynamics can be enhanced by all colleagues on our teams.

‘Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced’ ( James Baldwin). If we cannot face the word resilience then we risk losing the opportunity to change, grow and develop as individuals and in our teams.

Anna Baverstock

Consultant Paediatrician and Associate DME supporting junior doctors

Taunton and Somerset NHS Trust

@anna_annabav

Anna.baverstock@tst.nhs.uk