It’s one of the delights of my professional clinical practice that (nearly) all the time, the diagnosis of a malignancy is hard & sound, reproducible, based on good data showing discrimination from other settings and with minimal interpersonal variation. Take a chunk of a particular renal tumour and show it to half a dozen paeds pathologists, and nearly all the time the Wilm’s tumour will be recognised and identified as such.

It’s one of the delights of my professional clinical practice that (nearly) all the time, the diagnosis of a malignancy is hard & sound, reproducible, based on good data showing discrimination from other settings and with minimal interpersonal variation. Take a chunk of a particular renal tumour and show it to half a dozen paeds pathologists, and nearly all the time the Wilm’s tumour will be recognised and identified as such.

People who deal with the un-biopsiable, the disorders without a test and with a requirement for artistic flair, both overwhelm me with their skill and terrify me with the Emperors New Clothes potential. Things like interpreting chest radiographs, or diagnosing Kawasaki disease and ADHD spring to mind. The methods used to guard against the off-piste clinician: regular group review; diagnostic criteria, checklists and the like; analysis of yes/no cohorts to detect changes in proposed outcomes, are all essential and undertaken regularly.

One area which has been subject to huge scrutiny because of the challenging implications of making/unmaking a ‘diagnosis’ is child abuse and neglect. The CORE-INFO group in Cardiff who have collected and reviewed thousands of studies have piled up the evidence for us, and these have been used to help guidelines for reproducible practice become established, yet there remains some difficulty in the finding of unexplained bruising.

Bruising without ‘usual’ traumatic cause, be that a collision with a car or a tumble on just-learning-to-walk legs, should prompt investigation for a bleeding disorder. This heterogenous group of problems with platelets, clotting cascades and interactions of the two can be fairly well classified. The severity of the bleeding tendency is quantifiable. Knowing your clotting doesn’t work right then explained the previously unexplained bruising … well… it might.

But what’s normal bruising look like in this abnormal population?

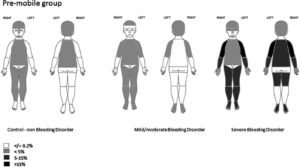

Aren’t you lucky that Peter Collins and pals at a group of bleeding disorder clinics in the UK collected a cohort of volunteers whose children had bleeding disorders of all sorts, and undertook repeated and regular assessments of bruising to describe the location of bruise according to mobility status, severity of bleeding problem and use of prophylaxis. They show the increased number of bruises, the difference in their location, and how these change over time. They are very clear to point out that these are the common and usual patterns, but that children with bleeding disorders may also be subject to inflicted bruising, and that even in these ‘delicate’ children, genital and ear/cheek/eye bruising was extremely unlikely and warrants significant further investigation.

The advancement of our understanding of health and illness in childhood needs people to undertake research in all sorts of areas, including those with complicated science underpinning the disorders and difficult implications of their findings, and it’s essential that we support people in doing these studies.