Tianqi Chen, Grace Kong, Bingliang Lin, Wenlong Lu, Jingfan Xiong

China is the largest tobacco producer and consumer in the world, despite significant recent progress in tobacco control. Smoking is still deeply ingrained in Chinese culture, often associated with social interaction. Recently, a troubling trend among primary school students has emerged and been widely reported online: the cigarette card game, which involves collecting and trading cards made from discarded cigarette packages.

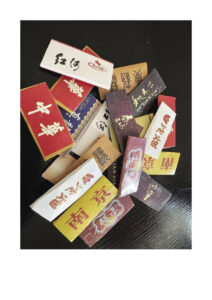

Cigarette cards are made by folding the lids of empty cigarette packages into square shapes (Figure 1), which are then used as toys. Cards are placed on the ground and flipped alternately; whoever flips the opponent’s cigarette card wins it. Recently, this game became popular among primary school students and was widely reported by the Chinese online media. According to online reports, cards are ranked based on cigarette brands, with higher-priced brands considered more valuable and thus ranked higher. Children are drawn to these cards for their colorful designs and the excitement of the competition. They typically acquire cigarette cards by collecting used packs from family members, scavenging from trash, or using portions of their allowances to build their collections. Some even urge family members to contribute more empty packs.

Figure1. Cigarette card reported in online news or reports in social media.

Widespread Dissemination on Social Media

In 2022, China had 191 million underage internet users, and 54.1% of them were frequent users of social media video platforms such as Douyin (internationally known as TikTok), Kuaishou and Bilibili. These platforms have become robust arenas for spreading the popularity of the cigarette card game in Chinese youth. A search “cigarette cards” reveals numerous videos showcasing the game, including tutorials on folding techniques, gameplay introductions, and rankings of cigarette cards (Figure 2), with some receiving over 100,000 likes. For example, one Douyin creator with over 1.5 million followers posted a video on cigarette cards that received 130,000 likes. Additionally a 15-year-old content creator posted 21 videos on his profile showing how to create these cards from various cigarette brands, attracting viewers who inquire about prices and expressing interest in buying them.

Figure 2. Contents related to cigarette card on Douyin.

Search results for the keyword “cigarette card” in Chinese on Douyin, including tutorials on folding techniques, gameplay introductions, and card rankings.

Youth access to cigarette cards

Cigarette cards are easily accessible to children. On Taobao, China’s largest online shopping platform, searching “cigarette card” results in over 6,000 listings, with the highest-selling items having over 20,000 orders (Figure 3). These cards are priced between 3 to 100 yuan per set of 10 (approximately 0.42 to 14.00 USD) and are marked with catchy slogans such as “direct supply, see who has more” and “high chance of rare cards, no need for mom to worry about me picking up cigarette packs anymore”. These cards are also sold in “cultural goods stores” online, which do not require age verification. There are also reports that children can buy these cards from small shops near schools.

Figure 3. Cigarette Cards Sold on Online Shopping Platforms.

Search results for “cigarette cards” on an online shopping platform.

Tobacco promotion has been related to positive attitudes, beliefs, and expectations regarding tobacco, and increases the likelihood of initiation. These games indirectly promote tobacco by familiarising children with brands and imagery, potentially normalizing smoking and reducing perceived risks and promoting early initiation through the “mere exposure” effect.

Cigarette card games also satisfy children’s need for peer acceptance and enhance their popularity through the collection of “rare” cards. Additionally, the game can evolve beyond simple collecting to include gambling behaviors, where losers must surrender cigarette cards or even money to winners. In some cases, trading cigarette cards among children has escalated from mere game play to actual gambling, enhancing the stakes and risks involved.

Regulatory and Cultural Challenges

The emergence of the cigarette card game underscores significant regulatory loopholes in tobacco marketing to children. Although the Chinese government has made efforts to prohibit cigarette advertising and curb illegal sales to minors, these measures are inadequate in addressing tobacco packaging exposure. Insufficient social media regulations further allow the spread of tobacco-related content mean that children still have easy access to inappropriate content. The effectiveness of content regulation is undermined by the platforms’ reliance on self-regulation.

These loopholes are amplified by poorly regulated package warnings and cigarette promotions that incorporate Chinese cultural elements, such as representations of Chinese plants, animals, and apparel/beauty. The WHO recommends all countries introduce plain tobacco packaging, which standardises all elements of the tobacco pack and removes colourful branding and imagery. The most recent 2015 pacakaging regulation mandated three-line health warnings to cover 35% of the bottom surface of cigarette pack, but in practice, warnings only covers about 15% of the package, allowing visually appealing branding to remain dominant.

In response to the cigarette card game, various regions in China have implemented targeted measures. For instance, in Meilan District, Haikou city, authorities launched a month-long campaign enforcing strict inspections and banning the game in schools and nearby areas. Gaozhou’s Dajing Town initiated a safety campaign against the illegal sales of cigarette cards around schools, involving multiple government departments. However, these efforts reflect a fragmented approach to enforcement.

The popularity of cigarette cards among primary school students calls for enhanced surveillance and early preventive measures to avoid jeopardizing China’s “Healthy China 2030” goal of reducing smoking rates to below 20%.

Tianqi Chen, School of Public Health, Peking University, People’s Republic of China, Other contributors to this article include: Grace Kong, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, USA; Bingliang Lin, Shenzhen Center for Chronic Disease Control, No.2021 Buxin Road, Luohu Distinct Shenzhen 518001, People’s Republic of China; Wenlong Lu, Shenzhen Center for Chronic Disease Control, No.2021 Buxin Road, Luohu Distinct Shenzhen 518001, People’s Republic of China; Jingfan Xiong, Shenzhen Center for Chronic Disease Control, No.2021 Buxin Road, Luohu Distinct Shenzhen 518001, People’s Republic of China.