Kelsey Romeo-Stuppy with Carolyn Dresler, Chris Bostic, Cheryl Healton, Laurent Huber, Harry Lando, and Martin Raw

When thinking of human rights crises, people often think of violence – child soldiers, genital mutilation, concentration camps – rather than health epidemics. However, tobacco corporations are guilty of one of the greatest human rights abuses in history. Tobacco multinationals entice consumers to become victims (almost always starting in childhood) through advertising and manipulating their products to be more addictive. The results are deadly. Tobacco use killed 100 million people in the last century; left unchecked, it will kill 1 billion people in the 21st century.

Public health advocates are working hard to diminish this entirely preventable tragedy, with some success, particularly in higher income countries. Smoking prevalence is falling in four WHO regions, but it is rising in two, and overall smoker numbers are rising due to population growth. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the world’s first global public health treaty, grounded in human rights principles, has made modest progress in reducing smoking prevalence. Strong implementation of measures implemented between 2007 and 2014 is estimated to have prevented nearly 22 million smoking-attributable premature deaths. However, while some FCTC measures have been well implemented, others have been seriously neglected, most notably tobacco cessation treatment.

The collective failure to offer and promote cessation support to tobacco users who need it is not only a public health failure, it is also a human rights failure. The human rights framework is grounded in the principle that governments have a duty to protect the fundamental rights of their citizens, including the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as specified in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the UN body authorized to monitor compliance with the ICESCR, also issued an authoritative statement on how governments should implement key aspects of the right to health when addressing access to treatment including, among others, its availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality. In this statement tobacco use was specifically addressed, describing “the failure to discourage production, marketing and consumption of tobacco” as a violation of the right.

To address these adverse corporate impacts on human rights, the UN adopted the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights which is based on three pillars: “Protect, Respect and Remedy”. These pillars underscore “the state duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business, through appropriate policies, regulation, and adjudication”. Corporations are obligated to respect human rights, which means to act with due diligence to avoid infringing on the rights of others and also to address adverse impacts as well as providing greater access by victims to effective remedies, both judicial and non-judicial.

Unfortunately, however, few governments have yet made tobacco cessation treatment widely available to their citizens. Further, States are not fulfilling their obligations to protect people from harms resulting from actions of the tobacco industry. The industry is not respecting human rights by their aggressive marketing of products that kill more than half of people who use them. Based on established principles then, the victims, in this case tobacco users, should, among other remedies, have access to effective tobacco cessation treatment.

Article 14 of the FCTC requires that Parties disseminate comprehensive guidelines on tobacco cessation and dependence, and promote effective treatment. Yet fourteen years after its adoption, only 40% have such guidelines and fewer still have a budget for treatment. In 2010 the Conference of Parties of the FCTC adopted detailed guidelines to help Parties implement Article 14. They recommended best practices for cessation treatment, yet according to the WHO only one third of the world’s population has access to appropriate cessation support.

In order to meet their human rights obligations under the FCTC and the right to health – enshrined in numerous places, but notably in the ICESCR – countries must create guidelines and implement them in a way that provides accessible and affordable cessation support. The FCTC Article 14 guidelines set out in detail how this can be achieved. The guidelines recognise that many countries will first want to introduce broad-reach low cost measures, and then as resources become available introduce more comprehensive measures, including behavioural support and affordable medications (a concept referred to in the human rights community as “progressive realization”). Tools (such as this and this) have been developed to help countries do this.

Tobacco cessation also impacts other government obligations, specifically, development obligations, which are also human rights obligations. By adopting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development UN member governments made a non-binding commitment to “seek to realize the human rights of all”. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include a target “to reduce by one third pre-mature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) through prevention and treatment” by 2030 (12). Tobacco cessation treatment prevents future mortality and morbidity from tobacco use but also treats nicotine addiction. The SDGs will not be met without more and better tobacco cessation.

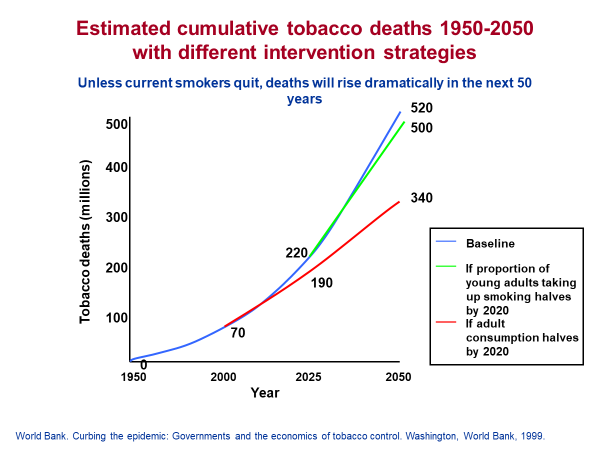

This World Bank diagram projected deaths by 2050 based on current trends (520 million), then with a reduction in smoking uptake by youth (20 million fewer), and finally with reduction from adult cessation (180 million fewer deaths). Importantly, only adult cessation will substantially reduce deaths from tobacco use in the short to medium term.

There are many policy options emerging for ending the tobacco epidemic for future generations. But in considering these, we cannot forget that in order to be truly tobacco free, governments must support and encourage cessation for current users. It’s not just a moral obligation, but a legal one for any government party to the FCTC or ICESCR. If care were withheld for those with other medical problems of such considerable public health magnitude, many would be incensed. Sadly, it may be true that those suffering from nicotine addiction are viewed as somehow deserving of their circumstances. However, given the corporate tobacco industry juggernaut behind this epidemic and the reality of initial addiction in childhood for the overwhelming majority, nothing could be further from the truth.

Many governments have failed to offer comprehensive, accessible tobacco cessation treatment for their populations, likely influenced by concerns about cost, and a sense that people are culpable for their addiction. Both of these assumptions are false. Low cost options exist that would help millions of people, and every dollar spent will be returned many-fold in health care and overall societal savings. The ongoing tobacco epidemic should be considered a public health emergency, and it cannot be appropriately tackled without comprehensive cessation treatment. Would we accept addressing the AIDS epidemic by withholding treatment? Governments have bound themselves to international norms that require action, and that action is instrumental to the long-term health and development of their countries.

Kelsey Romeo-Stuppy is the Managing Attorney at Action on Smoking and Health, USA. Carolyn Dresler is with the Human Rights and Tobacco Control Network, USA. Chris Bostic is the Deputy Director for Policy, Action on Smoking and Health, USA. Cheryl Healton is the Dean of New York University College of Global Public Health and Professor of Public Health Policy and Management. Laurent Huber is the Executive Director, Action on Smoking and Health, USA. Harry Lando, is a Professor with the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. Martin Raw is Visiting Professor at New York University College of Global Public Health.