Author: Christiaan A. Rhodius

Designation: Elderly Care Physician / Consultant in Palliative Medicine

Place of work: Hospice Bardo (Hoofddorp – the Netherlands)

Email address crhodius@hospicebardo.nl

LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/christiaan-rhodius-5864a530/

ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5757-887X

Collaborating partners in the this project and blog are:

Gustav Jørgen Pedersen (MUNCH)

Jarle Breivik, Hanne C. Lie and Carolina Borges Rau Steuernagel (Department of behavioural medicine, faculty of medicine, University of Oslo)

How Edvard Munch helps unlock ‘the secret’ of death

“I will tell you a secret,” she whispers. The 60 year old lady is clearly exhausted. Still, her eyes look lively. She has just been readmitted to the hospital due to another infection. The metastasized breast cancer has rapidly weakened her. I visit her to talk about the time to come and she is about to tell me her secret – “The only people around here that don’t seem to understand that I am dying are the doctors,” she continues. “Or they might be afraid to talk about it. Or feel incapable of discussing it. But you know, I am not afraid to die. Truly I am not. All I want is that I will die like my mother – surrounded by people who care for me and give me additional medication if necessary.”

“So no more antibiotics or…,” I try to summarize our conversation, but she interrupts.

“None whatsoever. Just bring me to the hospice,” she says gently but firmly. “Thanks for coming by. You know, you are the first doctor I have been able to talk to about dying. It has been a great relief. Thank you.”

You can hear a pin drop. The medical students listen wide-eyed as Christiaan Rhodius shares his story in the auditorium of the MUNCH (the Munch Museum in Oslo). He is palliative care consultant from Hospice Bardo in the Netherlands, currently living in Norway. The students participate in a seminar called ‘Explore Life and Death with Munch’ which is part of the elective course ‘Cancer and Communication’ at the University of Oslo.

Photo: Petter Hveem, Nasjonalt senter for aldring og helse (The Norwegian National Centre for Ageing and Health).

We discuss how the story may enlighten us. This patient experienced that doctors avoided talking about death, making it ‘a secret’. Maybe because death is generally conceived as a medical failure rather than an intrinsic part of life. But by not talking about it, they miss out on a crucial ingredient of care: human connection. Moreover, they miss out on important information, like this woman’s well thought-through wish to be admitted to a hospice and die there.

The case represents a classic example of a common medical pitfall: To focus on measurable parameters, while ignoring the human and existential dimensions of care. Doctors prescribe antibiotics and other treatments before answering the question: “What is the goal we are pursuing?” – a question that only the patient can answer. Finding the answer requires focus beyond the physical aspects. It also needs connecting on the level of feelings, emotions and views on life.

Photo: Petter Hveem, Nasjonalt senter for aldring og helse (The Norwegian National Centre for Ageing and Health).

So how do we teach this skill to future doctors? How do we communicate about ‘the secret’?

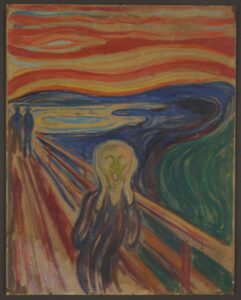

“Art broadens the horizon. It invites us to see new perspectives,” explains Gustav Pedersen. He heads the ‘Edvard Munch Center for Advanced Studies’ and holds a PhD on Munch and the role of death in art. He helps us see anew by showing and discussing the works of Munch, an artist well known for using death as a theme throughout much of his work. Social interactions, emotions and death are vividly illustrated – so vivid it makes you want to scream.

Groups of students move throughout the museum. They choose a painting for a conversation about death. What do you see – first on the factual level, then on the emotional level? What emotions move within you? How do these expressions relate to your own experiences? After having a personal “conversation” in front of the painting, members of the group share together.

“We had such an interesting conversation,” one of the students exclaims. We are back in the auditorium and the groups share their experiences in the final plenary session. “We looked at the same painting, but we discovered that all of us experienced different emotions,” she continues.

“I was focusing on the dark cloud and you looked at the colourful flowers,” a group member adds.

A third student joins in: “It wasn’t easy at first – experiencing one’s own emotions – let alone sharing them. But we experienced that it was possible – enriching.”

As the program comes to an end, we discuss the final question: “How could this experience alter your clinical approach as a medical student and future doctor?”

Three remarks may summarize the lessons learned:

“The experience with the paintings helps me to look for alternative ways of viewing the situation at hand.”

“I learned that it is OK to experience emotions myself and that sharing those emotions is possible.”

“It encourages me to dare ask personal questions – because death should not be a secret.”