By Dr Matthew Doré (Chair of Palliative Care Congress) and Dr Alan McPherson (Chair of The Regional Palliative Medicine Group)

“I don’t want thickener!”, “I want to eat it, not down my RIG” or most commonly “I want my roast dinner and all the trimmings, not smooshed!” Sound familiar?

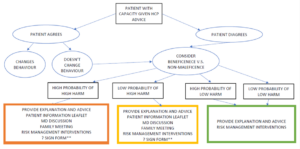

There has been an ongoing debate in our hospice. What was once easily swallowed has become harder to get your mouth around. A ‘risk feeding’ MDT form has been created for our patients. The form outlines and quantifies (as much as able) the risk and then ask the patient (or in their lack of capacity the family) to sign. Especially if the patient is not compliant with recommendations and wishes to have a bacon butty.

Is this a compassionate way of allowing patients to have their wishes while simultaneously protecting the staff should anything go wrong?

Let’s dig right into this juicy medium rare steak of a topic.

The assessment of the patient, the grading of the requirement, is commonly done by the excellent speech and language specialists, aptly named ‘SaLT’ adding to the zest and flavour of their role, or maybe a preservative of life?

The often touted MDT decision, however, when the patient disagrees with the recommendation, is often less ‘MDT’ as more ‘doctor you can override my recommendations’, a technician of risk stratification. A condiment in the decision making process.

And I understand their reluctance, the responsibility shouldn’t hold with one aspect of the MDT. I repeat, it shouldn’t hold with one aspect of the MDT.

So a meal was cooked, chewed and consumed by the whole MDT whilst discussing what solution was best, and surprised by our own ingenuity, a novel idea was contrived, (another) form was made. This magical piece of paper protecting both the pillars of governance and best practice. Alas, this created more questions than answers.

Matt cooking dangerously, taking whisks.

Such as what is the definition of ‘at risk feeding’? Like how to heat milk, no-one knows. Are we not all at risk of choking? Where is the line of choking acceptability? Even if someone drinks hot coffee slush puppies are they not still at risk to some degree? If so do we enforce it with the same vigour?

However, the most contentious debate centred around the signature. Should we have a patient or family (if patient has no capacity) sign to allow ‘risk feeding’? – whatever that is?

Frankly, this is nuts (and nuts are a choking hazard). This inadvertently puts pressure on the patient and family. Indeed, if the patient is very compliant, such as Mrs Betty Agreeable, who thanks me again and again irrespective of the inordinate amount of horrible procedures we have done to her, she will always agree, never daring to be non-compliant with the nice healthcare staff. She fears the potential, thus never more will she get her desired roast Turkey at Christmas. If they do sign, thus taking all responsibility, and unfortunately they do choke, it wholly lies on themselves or their family, leaving guilt and regret in the wake – ‘I should have taken that advice’.

As healthcare professionals if we do this, it feels as if we are ‘washing our hands’ of any responsibility, on your head be it.

This issue of getting the patient to ‘sign’ has already been suggested for other documentation, such as ‘risk of falls’ and ‘risk of pressure sores’. Therefore we have to think very carefully. Where does patient consent versus medical responsibility begin and end?

So what should we do?

According to the ‘Equality and Human Rights Commission’: 1

“- that the right to adequate food should ‘not be interpreted in a narrow or restrictive sense which equates it with a minimum package of calories, proteins and other specific nutrients’, but implies it should be:

- available in sufficient quality and quantity to satisfy dietary needs

- free from adverse substances

- culturally acceptable

- accessible, both economically and physically”

Our ‘Human Rights’ do not mention modality of food, i.e. via RIG or PEG or even thickened, but, it is a ‘Right of adequate food and water’.

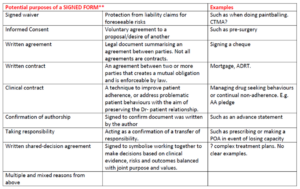

What about signatures?

A legal definition of a signature always pertains to forming contracts. The legality website defines it as such: 2

“A signature conveys:

- The identity of the parties entering into a contract

- The definite acceptance of the contract by the parties themselves

- The applicability of the terms and conditions of the contract with the parties”

Okay, but what about our immediate practice in medicine of obtaining consent prior to surgery. The GMC outlines in ‘Decision making and Consent’ 3 document in the section ‘taking a proportionate approach’. This outlines most interventions do not need a signature and verbal consent is adequate.

Indeed, obtaining a signature prior to a procedure or surgery is understanding the risks of medicine doing something to you, that something the doctor doesn’t have to offer if inappropriate. As per our Human Rights however, we can NEVER refuse to give food and water.

I worry that in creating a signature and thus contract regarding food and water, we abandon our patients in an unsupported risk averse way. This is neither compassionate nor co-operative.

Do we have a solution?

Nope. Below are some appendices of us attempting to outline our thoughts. But we are left with a unsavoury taste in our mouths and a whole bunch of questions.

Given swallowing difficulties are part of normal dying are we over-medicalising dying? Is this a legalistic influx into healthcare? But what legal protection is there for staff if a patient chokes after expressing their wishes to suck humbugs and the family complains? Does feeding via RIG/PEG neglect the need for an oral route and we can refuse to give oral food? Or does the Human Rights intervene? Indeed, is it ethical to refuse food in any circumstances? What about in the dementia patients? What are the consequences for other similar risk areas, falls, pressure sores etc. Do they need signatures? Indeed, why don’t we get the patient to sign DNACPR forms? What about time as a factor, lower risk with high consequences over a longer period compared to a shorter time period and lower risk? Indeed, all aspects of managing uncertainty. And thus who, or what team takes overall direction on this? The assessors are the most close understanders of the risk, but how to make it a cohesive MDT decision?

What is certain is this issue is no gag.

- https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/advice-and-guidance-human-rights-multipage-guide/right-adequate-standard-living-ombudsman-schemes

- https://www.leegality.com/blog/whats-a-signature

- https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/gmc-guidance-for-doctors—decision-making-and-consent-english_pdf-84191055.pdf