Preparing for quality: East London’s transformation has begun

Dr Amar Shah is a consultant forensic psychiatrist and quality improvement lead at East London NHS Foundation Trust. He is also the London regional lead on quality and value for the Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management. This blog is brought to you by BMJ Quality. For more quality improvement resources go to quality.bmj.com

Contact or follow him on twitter @DrAmarShah

At East London, the question we have been asking ourselves is, “what does it take to sustain a multi-year organisation-wide improvement programme that delivers significant improvements in quality and cost, and successfully transforms the culture of the organisation?”

Quality has been the undisputed buzzword in healthcare in 2013, with a number of seminal national reports focusing on how to improve quality of care. This blog will chronicle the journey of one provider of mental health and community services, and how we are changing our thinking and approach to quality.

At East London NHS Foundation Trust, we believe we currently deliver a good quality of care, with many ‘bright spots’ of excellent caring practice and innovation. There is also considerable inconsistency and variation, with some ‘dark spots’ of concern. This situation is not unique to East London, and most healthcare staff may be able to relate to a similar picture in their organisation. Over recent years, as with many NHS providers, our Trust has placed emphasis on quality control and quality assurance structures. This has resulted in relatively robust governance procedures, evidenced in the attainment of CQC essential standards of care for all visits and NHSLA level 3 risk management standards.

Our ambition is to deliver the best possible mental health and community care to our patients, service users, carers and families. We have made a commitment to quality of care. This is embodied in our mission to provide the highest quality mental health and community care in England by 2020. We recognise that achieving this will require a new approach to quality. The three landmark reports in 2013 on quality and safety in the NHS (Francis report, Keogh review and Berwick report) have all espoused the development of an organisational culture which prioritises patients and quality of care above all else, with clear values embedded through all aspects of organisational behaviour, and a relentless pursuit of high quality care through continuous improvement.

In addition but not unrelated, funding for the NHS is likely to remain static or possibly decline in real terms beyond the 2015 general election. Achieving year-on-year efficiency savings by focusing on rationalising inputs to the system (workforce, assets) is proving increasingly difficult and is likely to disproportionately affect staff morale and quality of care. It’s abundantly clear to anyone working in the frontline of healthcare delivery that the area of greatest inefficiency within the system lies within the clinical processes themselves, which have largely remained untouched through recent years of efficiency savings. Redesigning clinical pathways with the ambition of providing patient-centred, high value care offers the potential to realise continued savings from the health economy whilst delivering an improved quality of service to our patients. Successful redesign at this scale requires improvement expertise, dedicated resource, rigorous application of a consistent methodology and a fundamentally different approach to quality, which involves putting patients and the families at the heart of the design and improvement work.

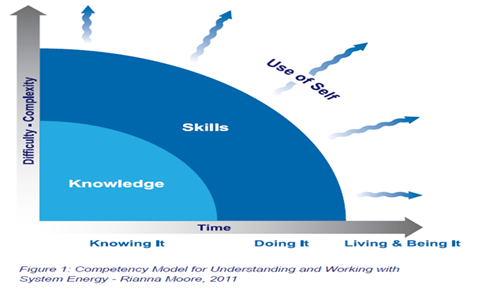

The last year of preparation has been a steep learning curve and a great investment. We have taken time to think, talk and learn from others. Successfully embedding a new culture and achieving a step-change in quality and value of care is a huge challenge, but we now feel in a much stronger position to attempt this.

Our work began at the very top of the organisation, recognising that Board-level leadership was absolutely vital to success. Nurturing and supporting improvement to achieve better health, better care and better cost requires leaders to apply a new approach and specific set of behaviours in redesigning systems and accelerating culture change, as described in the recent IHI white paper. Our Board has invested time and energy to understand improvement, to learn from the journey of other high performing organisations, and to develop a strategy for our programme of work. Wide consultation across our clinical teams, service users, carers, Governors and commissioners has fed into the development of a strategy that we hope all can feel ownership of.

Developing the business case has been a significant challenge, with most of the evidence and experience of large scale quality improvement being in acute care. However, we believe that coordinated improvement work in mental health and community health services is just as possible, despite some additional challenges, and we are excited by the prospect of starting to work in unchartered territory.

The work before the work of improvement has been crucial in preparing the ground for applying quality improvement across a whole organisation, and eventually a whole system of care. One of our earliest decisions was that we would be more successful in this journey if we partnered with an external continuous improvement expert, to support us with strategic advice and to help us build improvement skills in our workforce at scale and at pace.

We are building a central quality improvement team in the organisation, to coordinate the programme of work and to be the internal improvement experts. Over the last few months, we have been slowly and steadily reviewing and re-aligning many of our corporate systems so that they will support our improvement work. Much of this has the potential to be transformative – for example, working towards the publication of complaints every month on our website, embedding a structure for listening at every level of the organisation, integrating quality data and making this available to every person in the organisation, reviewing all of our policies and procedures to ensure they support the development of a just culture, reviewing our clinical audit programme, refreshing our induction process, and ensuring that quality improvement is embedded within all of our internal training and development.

Alongside this, we’re developing the framework for measuring and evaluating our progress on our strategy – not an easy task, considering the lack of standardised outcome measures in mental health, and the lack of accurate tariffs and costs for patient-level activity.

We’re clear that our quality improvement programme will involve a fundamental change in the way things are done. It will seek to bring about a culture change, putting patients at the heart of all that we do and at the centre of our improvement and redesign work. We want to embed a culture of listening more to our frontline staff, service users and carers, and provide more freedom to our frontline staff to work in partnership with patients to innovate and test new ideas, whilst stopping activity of lower value. And we want to build up the skills in our workforce on improvement, and support them to use a consistent methodology to test ideas, measure their impact and then spread successful change. We’re convinced that freeing our staff to work with their patients in improving the system and pathways of care will yield the greatest improvements in quality and cost outcomes.

We’re about to open a new chapter in our organisation’s journey. It’s one that we believe could only be possible from a position of strong leadership, assurance and financial security. Our next challenge is the critical one of engaging the whole organisation in this programme, and the next blog will describe how we’re attempting to create a movement for change that is led and owned by the grassroots.

References

1. Dixon-Woods, M., Baker, R., Charles, K. et al. (2013) Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Quality Safety doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001947

2. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry (chaired by Robert Francis QC), February 2013

3. Review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital Trusts in England (Professor Sir Bruce Keogh), NHS England, July 2013

4. A promise to learn – a commitment to act. Improving the safety of patients in England. National Advisory Group of the Safety of Patients in England, August 2013

5. Swensen S, Pugh M, McMullan C, Kabcenell A. High-Impact Leadership: Improve Care, Improve the Health of Populations, and Reduce Costs. IHI White Paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2013.