Empathic Redesign of the Ninewells Hospital Environment

Morven Millar 3rd year Medical Student University of Dundee

Morven Millar 3rd year Medical Student University of Dundee

Morven Millar is a 3rd year Medical Student at the University of Dundee, she wrote the blog from her experience working together with Art and Design students on this project. We worked with Jackie Malcolm a Graphic Design Lecturer from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design at the University of Dundee and Rod Mountain an ENT surgeon in NHS Tayside who came up with the original idea of getting Medical students and Art and Design student to work together.

Art and Design and Medicine, distinct fields that I had until only recently considered as separate entities. But through taking part in a project at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee I discovered that these two disciplines can indeed work together, and are powerfully linked by a common theme: Empathy. In Medicine empathy is fundamental to how we deliver individualised care to each patient, and it is the hope that every clinician has an empathic approach to making each decision. However, as a scientific discipline, the approach can easily become “task-based” as opposed to “user-based”, and this is where the medical field could learn a thing or two from the world of design. The project I took part in, as part of a QI module, aimed to unite students from Dundee University Medical School and Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design for “Empathic Redesign of the Ninewells Hospital Environment”. This involved considering the design of Ninewells Hospital with an empathic approach, with the hope of improving the overall experience for the thousands of people walking through its doors each day.

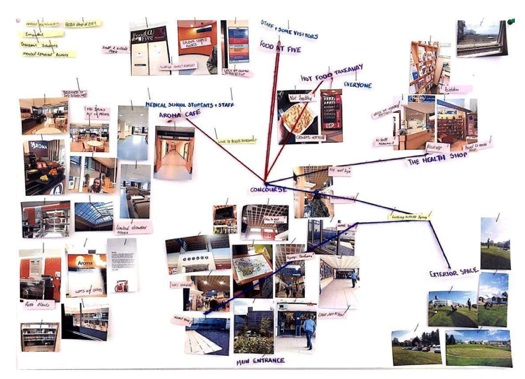

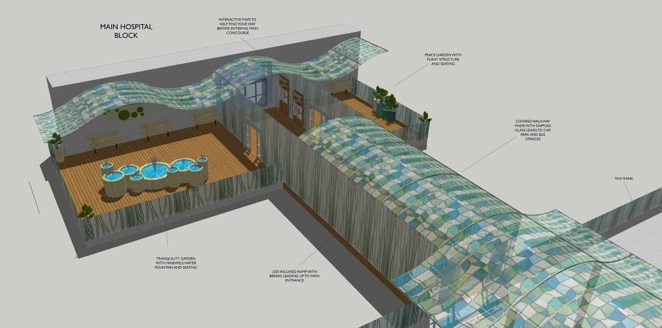

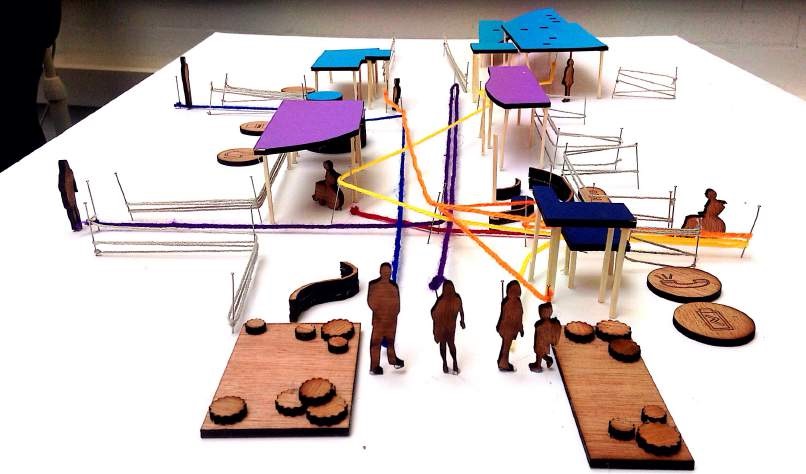

The brief for the project was to redesign the main concourse of the hospital, and to also consider how to link the inside space with the hospital’s unique and extensive grounds. The challenge was that each group was to focus on the experience of different patient groups, each with some form of disability or barrier to their environment. The six population groups that were considered were those with a physical disability, hearing impairment, visual impairment, dietary requirement, a new cancer diagnosis, and those for whom English is not their first language. The idea was that we would consider how these different patient groups would interact with the hospital environment, understand some of the challenges they might face, and what potential needs they would have and how to address them. Finally, once all this was considered, we were to redesign the hospital concourse in a way that would address some of the potential challenges for these patients, and improve their overall experience of their hospital visit. This user-focused approach is known as “empathic design”, a technique which is set apart from other product design methods in a few aspects. While most methods use observation for research, in empathic design “observation is conducted in the customer’s own environment”.[1] Another aspect unique to empathic design is the involvement of “interactions among members of an interdisciplinary team”,[1] which is beneficial in making observations as people from different disciplines will identify different information from the same situation.

Having walked through the concourse nearly every day for three years, I had become immune to its imperfections and problems, but when the design students visited the hospital they immediately picked up on several flaws and design opportunities (showing the advantages of bringing a fresh pair of eyes to a challenge, as well as a background in design). It certainly seemed ironic that there could be so many unidentified problems for the patient groups we were to focus on, as these people would undoubtedly be accessing healthcare. After conducting our initial observations and research we went, quite literally, to the drawing board (for the first time for many of the medical students). We were led by the design students in employing various methods which are often adopted in the fields of interior and graphic design. One of the techniques used included creating “personas” – fictional characters representing potential users of a particular space or product, how and why they might use it, and what sort of challenges they could face in the process. This was an interesting technique as it very much required putting oneself into the shoes of the “client” (particularly when we mapped out potential routes they would likely take through the concourse) and so entirely fit the bill for empathic design. After three weeks of work we presented our ideas to a panel of judges, and the hope is that many of these will be taken forward into the final design and renovation of the concourse and outdoor environment.

This experience was quite a unique opportunity, which was a privilege to be involved in. As students, there is a lot we can take away from this project, having had the chance to gain some insight into a different discipline. There is some debate as to whether medical students lose empathy as they progress through their studies, with evidence to support either side of the argument.[2] By taking part in a project that forced us to think about the needs of individuals from a non-medical point of view, acted as a reminder that the most important component of healthcare service we provide is the person at the centre of it, and what makes a truly patient-centred approach. Thus, regardless of the side of the debate the evidence best supports, I think this kind of project would be of benefit to all medical students, particularly those with an interest in art and design. And of course, for some of our work to improve the way patients access and experience their healthcare would be an incredibly rewarding outcome of our collaboration.

References

- Leonard D, Rayport J. Spark innovation through empathic design [homepage on the Internet]. Harvard Business Review. November 1997 [read 10/07/16]. Available from: https://hbr.org/1997/11/spark-innovation-through-empathic-design

- Quince T, Kinnersly P, Hales J, Silva A, Moriarty H, Thiemann P et al. Empathy among undergraduate medical students: A multicentre cross-sectional comparison of students beginning and approaching the end of their course. BMC Medical Education. [Serial on the Internet]. Mar 2016; 16:92 (read 29 Aug. 16).

Faculty:

Jackie Malcolm. Lecturer Graphic Design, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee

Rod Mountain, ENT Consultant, NHS Tayside

Vicki Tully, Teaching Lead for Patient Safety, Medical School, University of Dundee/NHS Tayside

Biography

Biography what really matters to users, and employ the narratives to inform patient focused service

what really matters to users, and employ the narratives to inform patient focused service