Patients and carers initiating quality improvement: The Dementia Buddy Scheme

Caroline Dearson is the founder of the Mickey Payne Memorial Foundation and the Dementia Buddy Scheme.

Caroline Dearson is a passionate carer and volunteer who founded the Dementia Buddy Scheme, and we at BMJ Quality are pleased to share her story. Here she describes how she collaborated with patients, volunteers, and carers after identifying that support after diagnosis was a major need for people who have dementia, as well as their carers. It was a small idea that became a big story (#smallthingsbigwins).

The Dementia Buddy Scheme was born as a result of the journey my family and I had to go through after my father was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2005. He was a Regimental Sergeant Major in the Royal Artillery for 22 years and a Yeoman Warder at The Tower of London for 23 years. Even with all that knowledge, he still got dementia.

My father went in and out of hospital through the A&E departments due to falls, confusion, and many other problems. He went into different wards for different reasons. These wards were equipped to look after other medical conditions – but were not prepared for someone with dementia. On several occasions, I offered to stay with him after he was admitted but was frequently told no, and referred to the visiting hours. Inevitably I would get calls at all times of the day, especially late night and in the early hours of the morning, to come and sit with him as he was disrupting the wards. The lack of support from the hospital wards put an unbearable strain on my family life, and I didn’t want other families to relive our experience.

In 2013 I met the ex-chief executive of South Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust (SEPT), Dr Patrick Geoghegan, and explained my vision for the Dementia Buddies. Straight away he wanted to be involved, and pulled out all the stops to get us onto his wards.

The Dementia Buddy Scheme was set up in 2013 on one ward at Thurrock Hospital in Essex. It is a voluntary scheme that involves individuals getting to know patients with dementia and visiting them as a friend a few times a week.

Buddies are now in place in three locations across Essex managed by SEPT, and are currently Buddied up with twelve patients at the moment. This can vary from week to week, due to new referrals and patients leaving.

The Buddies are person-centred and are on a rota that goes to the wards at the beginning of each week. This helps the staff to know exactly who is coming in and who they will be seeing. The Buddy’s individual rota goes out to them on the weekend before that week starts, letting them know exactly who they will be going into see. We try to keep the same Buddies to the same people while on the wards, ensuring that a trusting relationship can be in place as much as possible.

Each person will have three Buddies and each Buddy will see three people, which is due to holidays, sickness, etc. As a Buddy, I research the background of each person on the wards; I go back in time with them, as this is where I find the memories are still active. Once I’ve done this, I put activities and games in place in our Buddy cupboard and let each Buddy know about that person’s background, giving them gentle advice (at first) about how they may be able to interact with them. For example, someone might enjoy the giant jigsaws (helpful for those with poor eyesight) or magic painting sets (which reveal a picture when activated with water) that I can respectfully photograph and laminate. Once laminated I can then give the picture to that person to put up in their room. The joy on that person’s face is just so rewarding each time we do this since they are so proud of what they are achieving. We have also done knitting with the ladies, and used Meccano (using a plastic set to avoid people getting hurt). On one occasion I took the Meccano with me to see if the gentleman I was visiting would be interested. I showed him the catalogue and let him choose, and eventually he chose to build a yacht. His focus and determination was immense. I mentioned this to his family and they told me he had been in the Navy, but had forgotten to let me know about this.

Since we are now in the second year of the Buddies, Anglia Ruskin University are evaluating the scheme to determine how much this is helping patients with dementia. The scheme also provides some respite for family members by giving them time to spend time with their sons, daughters, and grandchildren without carrying any guilt, as well as freeing up staff on the wards. Currently we are supporting the families with seven Buddies (myself included) with five more waiting to be trained; I couldn’t have set this up without being actively involved myself.

Although this evaluation is important to the scheme and our future on wards and care homes, I personally see the successes on a daily basis through my interaction with the families and the Buddies. As the daughter of one of our patients recently commented, “I have the utmost respect and appreciation for the buddies and gather great comfort from knowing that someone is there for mum when I can’t be. Caring for a relative with dementia is a very hard journey for all involved, with good, bad, and sad days; the buddies help make my sad days, good days.”

Our training and disclosure and barring service (DBS) checks were carried out by SEPT NHS, but now I carry out the training and the DBS and occupational health checks are paid for by SEPT. The Buddies have the support of the staff on both of the wards.

The Foundation and I would eventually like to see Dementia Buddy Schemes in all hospitals, as well as all wards that have dementia patients, not just specialist dementia wards. I would like to also use our idea in care homes – that is my vision.

If you would like to know more about the Dementia Buddies, or would like to know how to become one in our area of Essex, please contact me on our email address: Mickeypaynememorialfoundation@hotmail.co.uk or mobile: 07539567553.

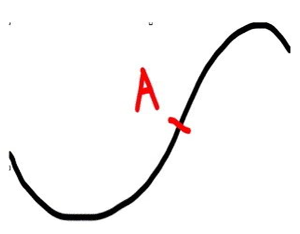

The simplicity chapter also describes Handy’s Curve. This is a well-known phenomenon in general management where any new initiative takes a short period to amass expertise or resources to get going and then has steady upwards growth. The sting in the tail is that by not planning the next steps or spread of the idea, death of the initiative is virtually guaranteed. The new ideas or changes need to be in place from the mid-point of the upwards curve – point A on the diagram. The NHS, as much of business, repeatedly fails to plan for the next steps early enough. Little wonder that staff get more and more sceptical about any shiny new initiatives delivering real sustainable change.

The simplicity chapter also describes Handy’s Curve. This is a well-known phenomenon in general management where any new initiative takes a short period to amass expertise or resources to get going and then has steady upwards growth. The sting in the tail is that by not planning the next steps or spread of the idea, death of the initiative is virtually guaranteed. The new ideas or changes need to be in place from the mid-point of the upwards curve – point A on the diagram. The NHS, as much of business, repeatedly fails to plan for the next steps early enough. Little wonder that staff get more and more sceptical about any shiny new initiatives delivering real sustainable change.