How to run a Quality Improvement Project (whilst working full time as a junior doctor)

Rob Bethune

Rob Bethune is a surgical registrar in the Severn Deanery. He was a founding board member of The Network (www.the-network.org.uk ) an on-line social media site for healthcare professionals wanting to share their learning and connect with other quality improvers around the world. He has been involved in a regional wide programme facilitating junior doctors to run quality improvement projects. This blog is brought to you by BMJ Quality. For more quality improvement resources go to quality.bmj.com

Effecting change as a junior doctor with little time, power and influence can be daunting. However there are ways of working through those difficulties. In this article I describe a few pointers that have helped junior doctors facilitate real change.

Establish a team and allow time

This is crucial, you cannot do this alone. Most of us do 4 or 6 month placements and this often not enough time to run a successful project and embed the changes, so develop a team of 6-10 people who will rotate through the clinical area throughout the year. As we shall see continuously collecting small samples of data is crucial to quality improvement (QI) and practically you need a group to collect this. Working in a team also makes it fun and gives you opportunities to bounce ideas of each other.

Get help

Ideally you want to find a permanent member of staff to mentor your project who has experience of QI and has spare time to meet with you and your team. In practice this is difficult unless you are in one of the few hospitals that has formal QI programmes for juniors. The BMJ Quality programme has a system of virtual mentors who can give QI advice. It also walks you through running a QI project and there are many previous examples on the open access on-line journal. Before you start your project you really must search this journal to see if others have run similar projects elsewhere and learn from them; try not to reinvent the wheel, let alone reinventing the flat tyre.

Use the Model for Improvement

This is the key. Clinical audit run by junior doctors has been overwhelmingly unsuccessful1-3. There are a multitude of tools for improving quality of systems (Lean and Six Sigma are examples) but the most tried and tested model for frontline clinical care is The Model for Improvement

It consists of three steps that are outlined below; set an aim, measure progress and make changes. The BMJ quality site has a lot more information and there are also a series of short videos on The Network YouTube site that explain the underlying methodology.

Aim: What is it you want to improve? It is really important to carefully define exactly what you are trying to improve. Make your aim SMART (Specific, measurable, assignable, realistic and time limited ). An example of this would be ‘Ensuring that by March 2014 95% of discharge summaries from the medical admission unit reach the GP within 24hrs’. Getting the aim right can be surprisingly difficult and may well change as you develop a deeper understanding of the system you are analysing. It is tempting to say ‘we want to improve discharge summaries’ but the lack of detail will make the next steps impossible.

Measure: ‘Data, data, data’ goes the drumbeat of a quality improvement project. Without out it you will not be able to see if your changes are an improvement. But more importantly during the process of collecting good data you will develop a deeper understanding of the system you are trying to improve. We often oversimplify problems and think that solutions are obvious. These simple solutions often fail as we don’t really understand the system we are dealing with. The very action of measuring a system gives us much more detailed understanding.

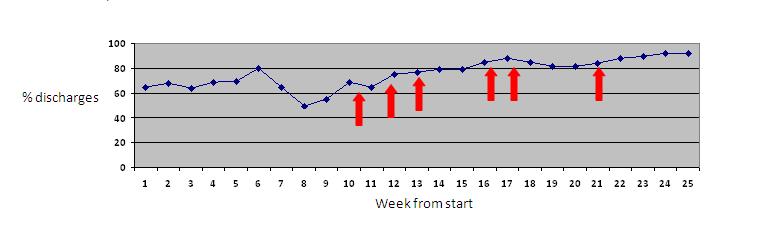

Then display the data using a run chart (see chart below). Collect small samples of data (10 each time is a good number) and do it as often as feasibly possible. Try and collect 10 sets of data before you start test of change, this will allow you to get a baseline and see if changes really are an improvement.

The plan-do-study-act-cycle (PDSA)

The plan-do-study-act-cycle (PDSA)

Now you have your background data collection and a more profound understanding of the system you are ready to make some changes. These are done in the form of PDSA cycles. It is a simple and intuitive as it sounds; come up with a plan, trial it out on one day, study the effect and act upon the result. One of the keys is to trial the change over a short time period in one area. If it works you can spread it but if it does not work and needs refining then you can do that easily. If you implement your idea widely from the beginning (as we have seen so often in healthcare) and you get it wrong it is expensive both on terms of time and resources to undo it. Make your first tests small. You can label you PDSA cycles on your run chart as in the example graph. Almost always multiple tests of change are needed , rather than just one intervention – this might explain why audit failed.

Publish

If you have run a QI project and improved care and equally importantly if your interventions did not work then you must share this with the wider healthcare community. The BMJ quality improvement journal is the perfect place to do this. Provided you have used the above methodology and have created a coherent story of change that others can adapt and translate elsewhere your project will be published.

It’s up to you

Improving the systems we work in is crucial to improving the care we give to our patients. As junior doctors we are in a unique position to see the problems in the delivery of frontline healthcare and affect the solutions. No-one else is going to do this, therefore do not send to know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.

References

1. Greenwood JP, Lindsay SJ, Batin PD, Robinson MB. Junior doctors and clinical audit. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1997;31(6):648-51.

2. Guryel E, Acton K, Patel S. Auditing orthopaedic audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008;90(8):675-8.

3. Hillman T, Roueche A. Clincal audit is dead, long live quality improvement. BMJ Careers 2011 http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20002524.