By Laura Klinkhamer

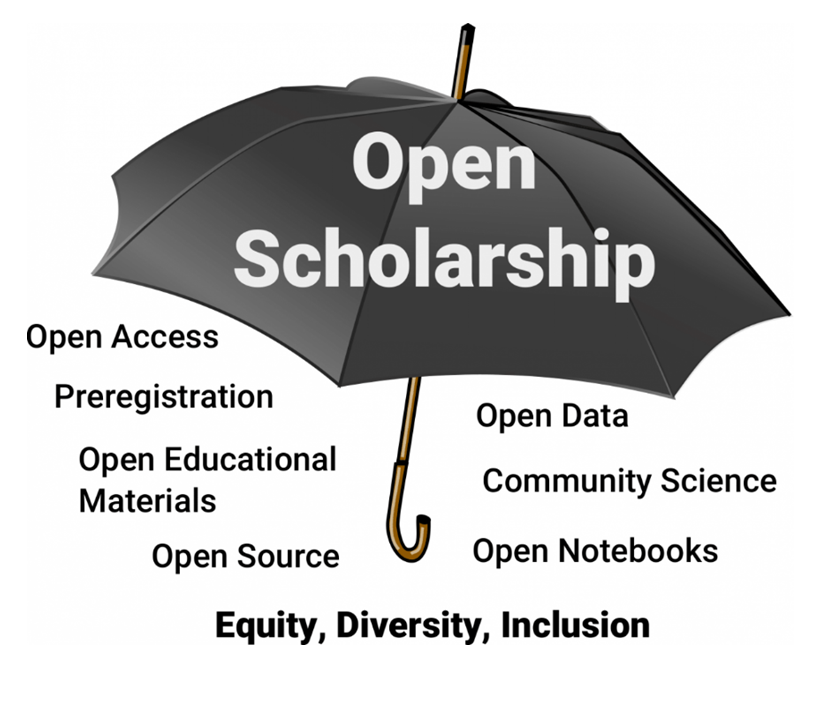

Equity, diversity, and inclusivity (EDI) should always be considered when planning and conducting research activity. The hierarchical world of academia is plagued by many EDI-related issues, including equity problems in access to (undergraduate) education [1] and a lack of diversity in higher rankings [2,3]. Unfortunately, the energetic and progressive open research movement is not free of these issues either [4]. If we want to make open research the norm for how research is being conducted, we have to acknowledge the central roles that equity, diversity and inclusivity play in widespread adoption of these practices (Figure 1) and the accompanying shift in research culture.

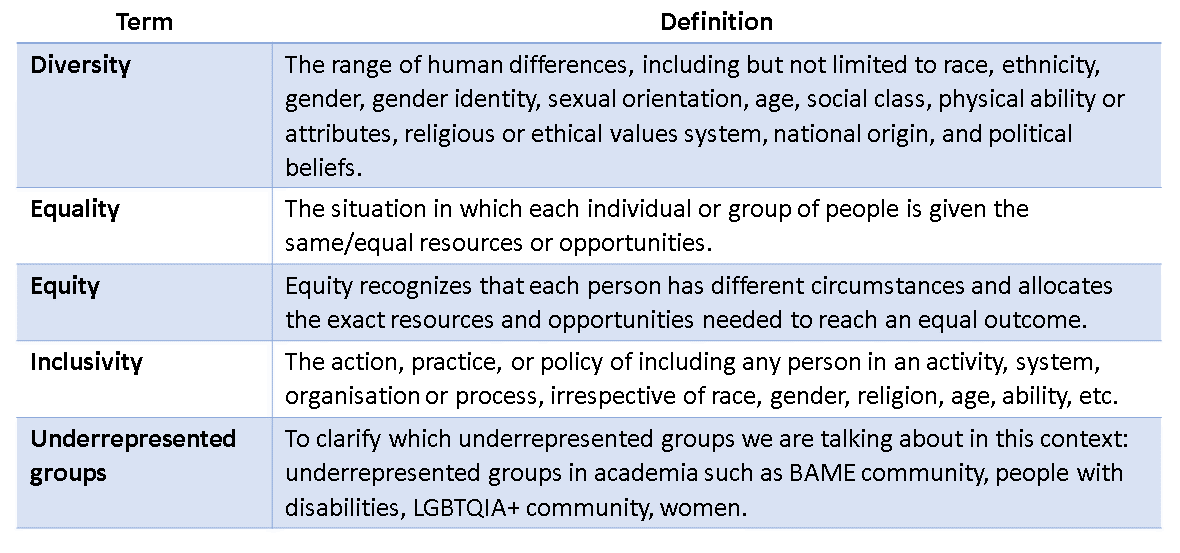

Edinburgh ReproducibiliTea hosted a panel discussion in March 2022, moderated by Dr Emily Sena, where Dr Nadia Soliman, Dr Kirstie Whitaker, Dr Catherine Talbot and Dr Olivia Guest came together to discuss EDI in open research. To ensure that everyone attending the session was aware of the relevant terms for this discussion, we sent our attendees the following glossary (Table 1):

Table 1. Glossary

Here, I will describe some of the highlights of the discussion.

Equity gaps in open research

Open research practices are not equally accessible to everyone. Equity gaps arise from differences between researchers for instance in location, institutional resources, lab/research group culture, race, ethnicity, disabilities and importantly career (in)security. As long as publishing in high impact factor journals remains the most important metric in researcher evaluation, and funding and promotion decisions are based on this metric, we cannot expect all researchers to take the plunge to switch to open practices. We need to acknowledge that these risks are larger for researchers who have more to lose when losing or stagnating their academic career, such as researchers with caring responsibilities. If we want to make open research the new norm for the way in which we do research, we need to conduct appropriate equity assessments and allocate additional resources where necessary to provide equal access to open research practices.

Who gets noticed for (not) doing open research?

EDI issues are also apparent when we look at the type of demographic who seem to receive most credits for visibly conducting open research practices (white, senior, male researchers) and, on the other end, the demographics that seem to receive most attention for not applying open research practices (junior, female researchers are targeted more)[5].

How to move forward

We asked our audience (~ 35 attendees, excluding the panel members) to discuss the following in small break-out groups:

If you would have the opportunity to have a 30 minute meeting with people in relevant positions in high ranks of the University (Lead for EDI, Lead for Open Research, Lead of Research (Strategy), what would you say to them? What would be the key points?

Combining insights from anonymously shared notes from the group discussions with insights from the main panel discussion, some recurring themes emerged:

- Top-down vs bottom-up approaches:

Participants were generally sceptic about the effectiveness of top-down approaches and were more favourable towards the potential of bottom-up approaches to tackling EDI issues in open research. Senior management should take a more facilitating role rather than a controlling role, supporting initiatives at local and grass-roots levels rather than introducing top-down strategies that may not connect very well with local needs. - Long-term vision, communication & transparency:

Senior management should develop a vision about a desirable, healthy research culture, which embraces open research principles and EDI principles. This vision should be informed by a diverse group of people active at the University, and by those who have decided to leave the University and academia. By hearing about the kinds of problems researchers face in their day-to-day activities, senior management can learn what is needed for researchers to thrive and allocate resources based on these needs. Leaders should appreciate the complexity of the issues at hand and realise that there is no quick fix and one-size-fits-all solution. Central decisions on actions to move towards this vision should be transparent and a diverse group, representative of the many people who will be impacted by these decisions, need to be able to respond to the proposed changes, ideally before they are implemented.

A long-term approach (10+ years) will be needed to address these deeply ingrained, large-scale issues. Although local initiatives can be a great start, we cannot realistically expect individual researchers to completely fix the issues, the task is simply too large. Senior management needs to make sure that there is a space for central conversations to take place, where individual experiences and best (leadership) practices can be shared with others to have a wider impact. - The role of rewards and incentives:

The panellists’ personal motivations for being active in undertaking open research practices and raising awareness about EDI issues were internally driven, not through external rewards. If anything, spending their time on these important issues limits their time to focus on activities that are rewarded by the system, meaning these activities are indirectly punished by the system.

Adopting a reward system to encourage open research practices can be beneficial, but has the inherent danger of becoming another system that can be gamed. Another risk is that the rewards may only reach the same people who already had more access to open research practices compared to others. Rewards and additional resources should be spent in a way that reduces the equity gap and enables more people to participate in open research practices. Ideally, rewards should go to those who have expressed interest in undertaking OR practices, but require extra funds/security to be able to do so.

There is an interesting similarity here with several open research practices, in that best practice seems to “frontload” the main planning and thinking. If we focus less on achieving a certain outcome, but focus more on supporting the process, it is likely that more favourable/valuable outcomes will arise naturally.

References

1. Hubble, S. Equality of access and outcomes in higher education in England. 45.

2. Claeys-Kulik, A.-L., Jørgensen, T. E. & Stöber, H. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in European Higher Education Institutions. 51.

3. Soliman, N. Leadership Training and Development – Academia’s Unmet Medical Need. BMJ Open Science https://blogs.bmj.com/openscience/2020/03/08/leadership-training-and-development-academias-unmet-medical-need/ (2020).

4. Whitaker, K. & Guest, O. #bropenscience is broken science. The Psychologist vol. 33 34–37 (2020).

5. Pownall, M. et al. Navigating Open Science as Early Career Feminist Researchers. Psychol. Women Q. 45, 526–539 (2021).

Laura Klinkhamer is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh (funded by Medical Research Scotland) and co-founder of Edinburgh ReproducibiliTea.

Laura Klinkhamer is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh (funded by Medical Research Scotland) and co-founder of Edinburgh ReproducibiliTea.

Conflicts of interest: none to report

Email: l.klinkhamer@sms.ed.ac.uk, laura.klinkhamer96@gmail.com

ORCID: 0000-0003-3424-6415

Twitter: @LauraKlinkhamer

Edinburgh ReproducibiliTea

Twitter: @Edinburgh_Tea

Edinburgh Open Research Initiative

Twitter: @Edinburgh_open