As part of the firearms special issue, authors Adelyn Allchin, Vicka Chaplin, and Josh Horwitz have contributed this blog post that articulates with their Special Feature Limiting Access to Lethal Means Applying the Social Ecological Model for Firearm Suicide Prevention.

Adelyn Allchin, MPH – Adelyn Allchin is the Senior Director of Public Health and Policy at the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. Adelyn oversees public health initiatives. Her current focus is on implementation and evaluation of risk-based firearm removal policies such as domestic violence restraining orders and extreme risk protection orders.

Vicka Chaplin, MA, MPH – Vicka Chaplin is the Director of Research Translation at the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. Vicka manages the Consortium for Risk Based Firearm Policy and oversees research translation initiatives that transform research into evidence-based policy, bringing research into the public discourse about gun violence prevention.

Josh Horwitz, JD – Josh Horwitz is the Executive Director of the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence and has spent three decades working on gun violence prevention issues. He is a visiting scholar at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health where he teaches public health advocacy.

Guns make suicide too easy. A suicide attempt by firearm is nearly always lethal and does not provide the opportunity to change one’s mind or abort the attempt. As such, addressing a suicidal individual’s access to firearms can mean the difference between life and death. In 2017, 23,854 people died by firearm suicide in the United States — more people than would fit in Madison Square Garden, New York City’s famed arena. Despite political resistance and a popular narrative that addressing access to firearms is too challenging, we must rise to the occasion. Lives depend on it.

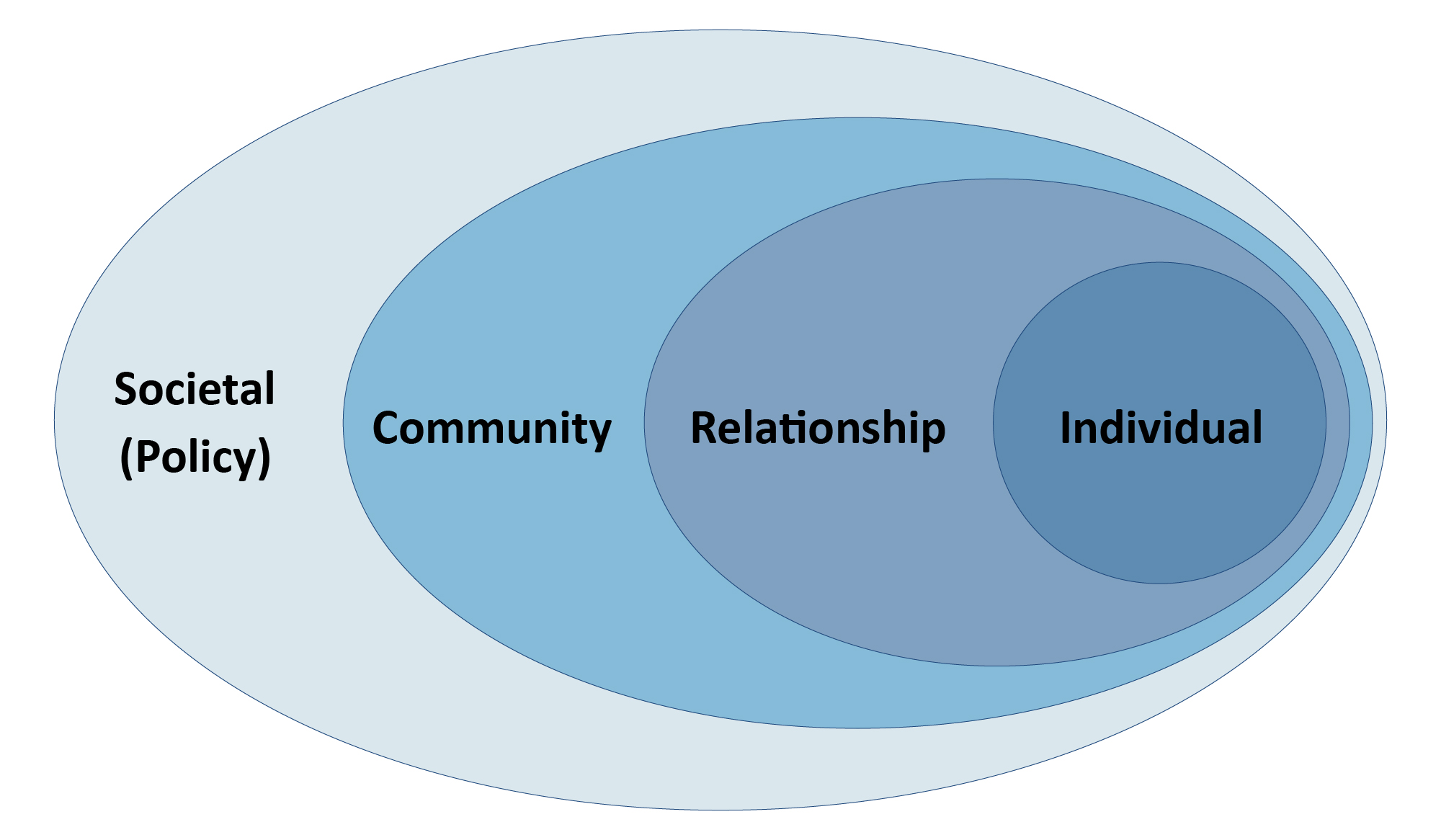

The social ecological model is a framework for understanding how societal, community, relationship, and individual factors work together for health and well-being. Our 2018 paper in Injury Prevention applies this model to firearm suicide prevention, focusing specifically on access to firearms. This approach is effective in part because access to firearms is both a significant risk factor for suicide and is easily modifiable. Despite social and cultural barriers to addressing access to lethal means, firearm access is a changeable characteristic, even if such a change is temporary. Other risk factors for suicide are often much more difficult to change and address. By focusing on reducing access to firearms, we provide a new conceptualization for addressing firearm suicide through the social ecological model.

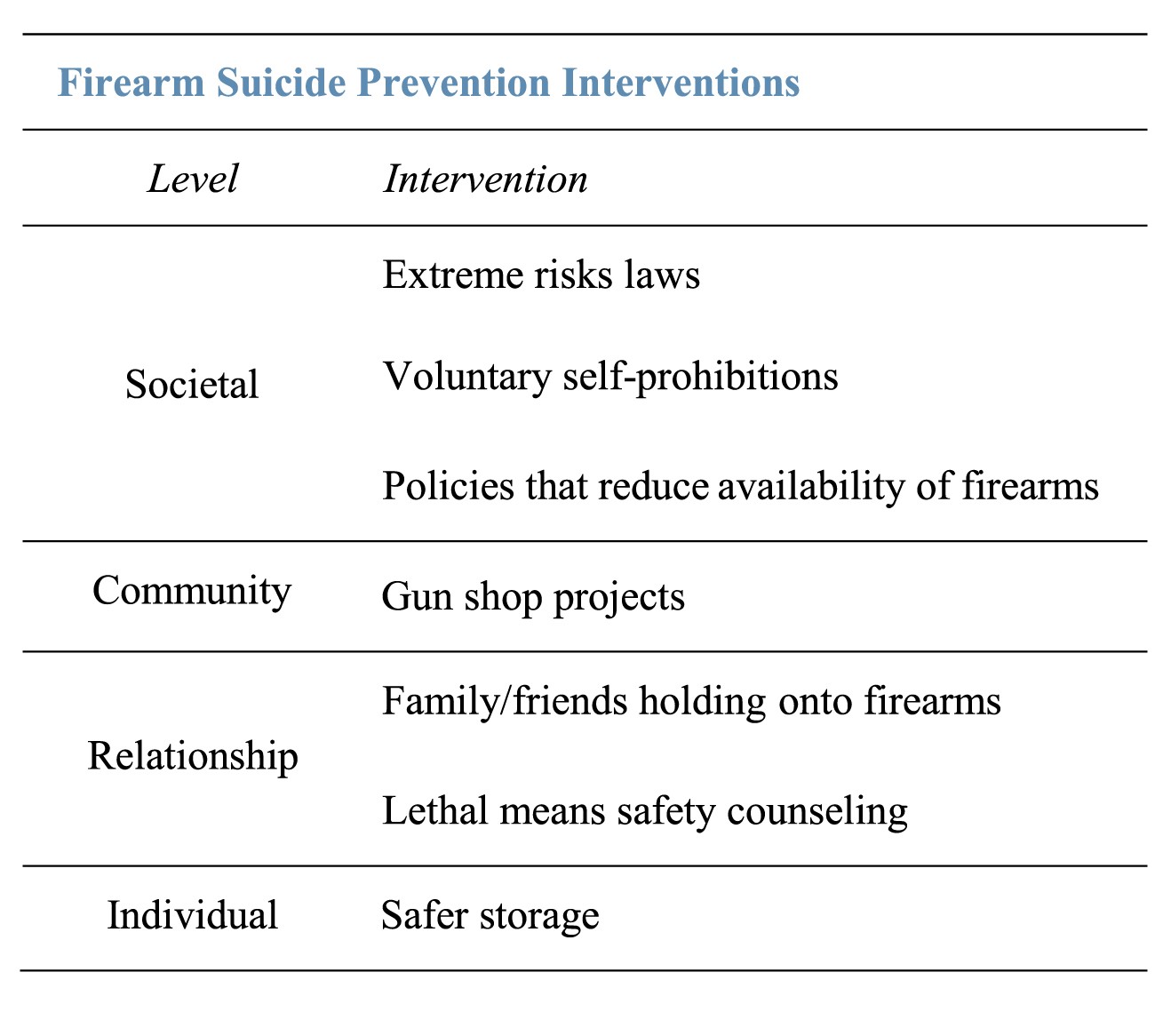

Beginning most broadly, societal level interventions include policies addressing access to firearms and cultural norms related to guns and suicide. Stepping down to the community level, institutional practices and policy implementation influence the local environment in which people live. Narrowing further, the relationship level addresses how close relationships may provide opportunities to intervene or influence an individual’s risk or access to firearms. Finally, the individual level focuses on personal history and biological factors, which may be mitigated through education, including education about the risks of owning firearms and improved knowledge about safer storage practices.

Some interventions operate squarely at one level of the social ecological model, while others cut across multiple levels. For instance, extreme risk laws address access to lethal means and can be used to examine several levels of the social ecological model.

At the societal level, extreme risk laws — also known as Extreme Risk Protection Orders and Gun Violence Restraining Orders, among other names — are civil court orders that allow law enforcement and/or family members to petition a court to temporarily remove firearms from individuals at risk of violence towards others or themselves. Notably, as of June 2019, 16 states and the District of Columbia have extreme risk laws — seven of which were enacted after the original publication of our paper just one year ago. Enacting these laws can change the policy landscape, and in the long term, influence cultural norms around the temporary removal of firearms from people at risk for suicide.

At the community level, we work to implement extreme risk laws. Collaboration between law enforcement, judges, and advocates is key to successful implementation. These stakeholders create new partnerships and institutional processes to make extreme risk laws accessible for people — like concerned family members or law enforcement officers — at the relationship level. Thus, not only are extreme risk laws being enacted and implemented around the country, they are actually being used to prevent suicides. For example, in Florida, an order was sought against a bartender who had an AR-15 and told a co-worker she wanted to die. In situations like this, temporarily removing firearms with an extreme risk order can save lives.

As knowledge about extreme risk laws and the risks of firearms access become more widespread, individuals may be motivated to take proactive steps to keep themselves and their families safe, like storing their firearms unloaded and locked separately from ammunition, storing them outside of their home, or even choosing to forego gun ownership altogether. Ultimately, attitudes and behaviors about gun storage may change, and new social norms on safer firearms storage will permeate the levels of the social ecological model, ultimately impacting the societal level through culture change.

Extreme risk laws are just one example of how interventions addressing firearm access may operate across levels of the social ecological model, and additional interventions should be implemented alongside them to create a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach to suicide prevention.

Importantly, our work does not end at Injury Prevention. We’re excited to be launching a website that highlights this model in an accessible, user-friendly format. Resources will be available for firearm suicide prevention interventions at each level of the model, and state-specific firearm suicide data will be available for each state. The site will be available on September 9 at PreventFirearmSuicide.efsgv.org. Follow the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence (@efsgv) on Twitter to learn more about the upcoming launch of the site.