Mohsan Subhani1, Simon M Everett2

Affiliations

1School of Medicine University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

2Gastroenterology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is one of the highest-risk procedures routinely performed by endoscopists (1). It is one of the most complex endoscopic procedures, often reserved for more advanced therapeutic interventions rather than routine diagnosis. Given its complexity and potential risks, ensuring that the highest standards of care are met is essential.

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) first conducted a national audit in 2007 to examine the quality of ERCP training and practice (2). In 2014, BSG published a standard Framework, introducing key performance indicators (KPIs) to guide ERCP practitioners (3). These KPIs focused on practitioner skills, service quality, and training programs to standardise care and improve patient outcomes. ERCP practice has significantly evolved over the years due to the availability of alternative diagnostics tools such as endoscopic ultrasound and

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and it should now mainly be performed for therapeutic purposes. The “Getting it Right First Time” (GIRFT) review and recent NHS white papers highlight the need for multidisciplinary teams, improved case selection, and regional consolidation to enhance quality and outcomes in ERCP (4).

In this #FGblog, we want to draw Frontline Gastroenterology readers’ attention to recently published BSG ERCP minimum service standards and good practice statements (5), exploring the driving factors behind these guidelines, and what they mean for both healthcare professionals and patients.

In 2021, BSG established a diverse multi-stakeholder ERCP project group including both healthcare professionals and members of the public. Two national surveys were conducted to assess ERCP practices across the UK, targeting both practitioners and endoscopy units. Discussion groups further explored these issues, integrating feedback to draft statements prioritising high-quality, safe ERCP services. The survey had a 100% response rate from all 170 UK endoscopy units and a 74% (389/526 respondents) response from ERCP practitioners. Final recommendations, based on consensus, are presented as good practice statements rather than formal guidelines. These focus on service delivery rather than the technical aspects of performing ERCP. Below is a summary of key statements.

Key Components of a High-Quality ERCP Service

The statements are grouped into categories: the patient journey through the unit, the ERCP team, CPD and clinical governance, safety and KPIs, equipment and services, and network provision with multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs).

Documents and Policies

A high-quality ERCP service requires comprehensive written policies and guidelines. 75% of organisations have clinical pathway guidelines, while only 23% have policies for temporary stent removal. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) reduce variability and enhance safety, as highlighted by reports linking the lack of SOPs to patient safety incidents. ERCP services should have dedicated policies covering vetting, consent, and adherence to published guidelines.

Pre-procedure: Referral and Vetting

Booking and vetting of ERCP cases should prioritise appropriateness and patient safety. While 58% of units use electronic referral systems, paper-based processes remain common. ERCP consultants are responsible for vetting referrals, ensuring patient fitness and the necessity of procedures. Inpatients require additional review by ERCP team members to avoid late cancellations or inappropriate procedures.

Timeliness and Waiting List Management

Effective booking and waiting list management are critical for ERCP services. Procedures should be scheduled with proper time allocation to ensure efficiency. Outpatient cases should be prioritized earlier in the day to enable same-day discharge. Additionally, units must track and audit compliance with ERCP timing standards, especially for urgent cases like CBD stones. Monitoring systems for stent removal are crucial to avoid complications such as biliary sepsis.

Consent

Consent processes for ERCP procedures vary across units, often falling short of BSG and ESGE guidelines. Many patients lack thorough communication about risks, especially in emergency cases. Pre-procedure discussions, preferably face-to-face or by phone, are recommended to ensure informed consent. Final consent must be confirmed by an ERCP-trained endoscopist.

Procedure

Patients undergoing ERCP often have comorbidities, requiring careful preparation, including medication review, hydration, and imaging. Specialist radiology support is crucial, especially for complex cases. Pre-procedure briefings and adherence to surgical checklists (e.g., WHO) ensure safety, with specific checks for ERCP, such as clotting and stent selection. Managing staff fatigue is important; breaks and lightweight lead gowns should be provided. Teamwork and a learning culture enhance outcomes. Pancreatitis is a common complication; adherence to prevention guidelines and early recognition of complications, like perforation, is vital. Clear escalation pathways should be established to manage adverse events.

Post-procedure

Recovery

post-procedure care focuses on safe recovery from sedation and monitoring for complications. Patients should be observed for at least four hours after the procedure, with trained nurses available to identify issues like pancreatitis.

Discharge

Discussions about the procedure should occur in private after recovery, involving the endoscopist and caregivers. Patients must receive clear discharge information about potential complications and guidance on when to seek help.

Follow-up

Tracking temporary stents is essential to prevent complications. Only 61% of hospitals monitor stent patients, so Trusts must establish reliable systems for timely follow-ups and removals.

The ERCP team

ERCP nurses must have specific competencies, including leadership skills, to ensure positive patient outcomes. A minimum of three trained staff is essential for each procedure, with one designated as the lead nurse. Management requires coordination between endoscopists, nurses, and administrators to ensure quality and efficiency. Patient engagement in the consent process is critical, as is collaboration with radiologists and surgeons for complex cases. Access to urgent surgical and interventional radiology expertise is essential for safe ERCP procedures, emphasizing the importance of an integrated approach within ERCP networks.

Continuous professional development (CPD), clinical governance, safety and KPIs

CPD is essential for high-quality patient care, yet many clinicians lack adequate ERCP-related CPD, with 53% having no dedicated time in their job plans. Robust clinical governance is crucial for monitoring safety and quality in high-risk ERCP procedures. KPIs indicate that individual endoscopists should perform a minimum of 100 procedures annually and units should perform a minimum of 200. All ERCP units must implement governance arrangements, designate clinical leads, and ensure compliance with KPIs to improve patient outcomes and care standards.

Equipment and services

The survey of ERCP facilities highlights areas needing improvement, with 50% of responders finding them mostly adequate but 14% deeming them somewhat inadequate. Space constraints in ERCP and recovery rooms limit anaesthetist-supported lists and safe patient recovery. Dedicated fluoroscopy rooms are essential, and all equipment should be easily accessible to optimize patient flow. Additionally, ergonomic considerations and proper radiation protection are critical for staff. Improved access to deep sedation/general anaesthesia (DS/GA) is needed, particularly for complex cases. Overall, adequate staffing, equipment, and procedures are vital to enhance ERCP service delivery and patient safety.

Network provision and MDT

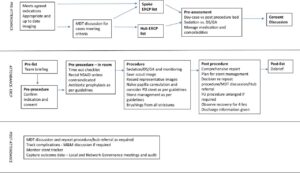

Regional ERCP networks, based on a hub-and-spoke model, enhance collaboration among specialities, optimize resources, and improve patient care. Key recommendations include developing care pathways, holding regular multidisciplinary team meetings, ensuring compliance with protocols, and auditing annual case volumes to ensure high-quality, timely interventions for pancreaticobiliary conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Role of a network in ERCP service provision (DS-deep sedation, GA-general anaesthesia, MDT- multidisciplinary team, M&M- morbidity and mortality, NSAID- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug)

Declaration

MS is a trainee associate editor for Frontline Gastroenterology

Twitter handles

@MohsenSubhani @SimonMEverett

References

- Baron TH, Petersen BT, Mergener K, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, et al. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. 2006;101(4):892-7.

- Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, et al. Are we meeting the standards set for endoscopy? Results of a large-scale prospective survey of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatograph practice. Gut. 2007;56(6):821-9.

- Wilkinson M, Charnley R, Morris J. ERCP, The way forward. A standards framework. 2014. 2018.

- Oates B. Gastroenterology-GIRFT programme national specialty report. NHS England. 2021.

- Everett SM, Ahmed W, Dobson C, Haworth E, Jarvis M, Kluettgens B, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) Quality Improvement Programme: minimum service standards and good practice statements. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2024:flgastro-2024-102804.