This week EBN’s Associate Editor Elizabeth Bailey summarises a recent report on global maternal mortality and considers drivers impacting progress in global maternal safety.

This week EBN’s Associate Editor Elizabeth Bailey summarises a recent report on global maternal mortality and considers drivers impacting progress in global maternal safety.

In recent months, a report describing estimates of global maternity mortality rates was published jointly by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division [1]. The report entitled Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020 [1] presented data which illustrated the variation in maternal mortality rates that persist across the globe and throughout the 20 years the report covered, as well as benchmarking progress against the Sustainable Development Goal to reduce the global maternal mortality rate to less than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030 [2].

The report which covered 185 countries and territories in the analysis contained some alarming figures,

- Globally, an estimated 287,000 maternal deaths occurred in 2020

- The overall global maternal mortality rate in 2020 was 223 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

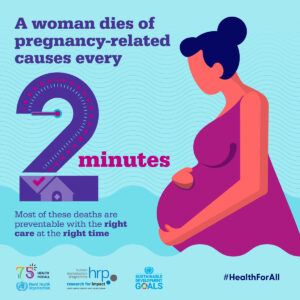

- This corresponds to almost 800 maternal deaths every day and approximately one maternal death every two minutes globally

- For a girl aged 15 years in 2020 there is on average a 1 in 210 risk that she will die from a maternal cause.

Overall there was cause for some optimism as between 2000 and 2020 the global maternal mortality rate fell by 34.3% from 339 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 223 in 2020, however, the trajectory of the decline stalled significantly from 2015 onwards [1]. In this time only two regions achieved a significant reduction in the maternal mortality rate during the first five years of SDG era, (Australia and New Zealand, Central and Southern Asia). The maternal mortality rate in Europe and Northern America increased between 2015-2020, with change of -16.5% and increased in Latin America and the Caribbean with change of -14.8% [1].

The period from 2015 to 2020 represents the start of the period covered by the Sustainable Development Goals meaning that significant progress will need to be made to reach the target of less than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.

Large regional inequalities persist with Sub-Saharan Africa as the region with a very high maternal mortality rate in 2020, estimated at 545 per 100,000 live births, with Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounting for approximately 70% of global maternal deaths in 2020. The lowest maternal mortality rate was in Australia and New Zealand at 4 per 100,000 approximately 400 times lower than in Sub-Saharan Africa [1].

In considering the drivers for such regional and sub-regional variation there are a few that may immediately come to mind. This includes access to healthcare, good coverage of universal sexual and reproductive health care, region-level wealth and gender-based rights within the sub-regions included all of which do indeed continue to be key drivers of maternal wellbeing. However, there may be additional factors at play in the complexity of these statistics and therefore adaptations to the global solutions offered are required.

There have been several global shocks in the years covered by the report, and in the years following the end of this reporting period. Global conflict and violence have risen, climate change effects are taking hold, there is further unequal distribution of wealth all impacted by a global pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic is known to have had a negative impact on maternal mortality, both in low and middle-income countries, again with great disparity on how significant these impacts were [3].

The number of international migrants worldwide has continued to grow over recent decades. The total estimated 281 million people living in a country other than their countries of birth in 2020 was 128 million more than in 1990 and over three times the estimated number in 1970 [4]. There is a marked trend for worse pregnancy outcomes among refugees and migrants and being a migrant is a risk factor for poorer maternal and newborn health [5]. Migrating families are more likely to experience barriers in accessing healthcare, including lack of certainty about financial support for healthcare, language and cultural barriers as well as possible lower socioeconomic status, and lack of social support [5].

Increasingly the impacts of climate change are resulting in extreme weather events and humanitarian crisis, pollution, food shortages and variation in clean water availability will impact maternal health. This will also drive further displacement of populations increasing global migration [6]. This interconnection of global factors and their impact on maternal mortality is why the efforts to meet the targets set out by all 17 Sustainability Goals are critical if SDG 3.1 is to become close to being achieved.

One intervention with the potential to have a positive impact on maternal mortality is midwifery care. In the commentary accompanying the Lancet series on midwifery published in 2014 it was suggested that midwifery has a pivotal, yet widely neglected, part to play in accelerating progress to end preventable mortality of women and children [7]. Barriers to implementing midwifery care globally include the social and economic status of midwives and the political situation of the region, still overwhelmingly women, who may in extreme examples not have the social freedoms to continue education or to leave the home to work, or in other regions are not awarded the autonomy within the established health system to support maternal health to maximal effect. The International Confederation recognises these issues in their Bill of Rights for women and midwives [8].

The global challenges that arise following changing political, economic, and societal influences continue to have a significant impact on maternal mortality. With increasing migration and displacement, every region must work to ensure its approach to improving maternal health care considers global drivers and the most vulnerable within their changing populations. There is much work to be done not only to achieve the SDG of reducing maternal morbidity and reducing inter-region variability, but also to get to a place where maternal morbidity can be protected from global shocks beyond healthcare pressures and where one day every part of the modern world is a safe place to be pregnant and give birth.

You can download the full report here: Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division

For further information on the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals see: Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals – United Nations Sustainable Development

- Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (with infographics available from Maternal health (who.int) [Accessed 05/04/2023])

- United Nations, Sustainable Development Goals, SDG 3.1 Reducing maternal mortality https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 [Accessed 05/04/2023]

- Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, O’Brien P, Morris E, Draycott T, Thangaratinam S, Le Doare K, Ladhani S, von Dadelszen P, Magee L, Khalil A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e759–72

- McAuliffe, M. and A. Triandafyllidou (eds.), 2021. World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva.

- Improving the health care of pregnant refugee and migrant women and newborn children. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2018 (Technical guidance on refugee and migrant health).

- Giudice LC, Llamas-Clark EF, DeNicola N, et al; the FIGO Committee on Climate Change, Toxic Environmental Exposures. Climate change, women’s health, and the role of obstetricians and gynecologists in leadership. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2021; 155: 345– 356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13958

- Horton R, Astudillo O, The power of midwifery Lancet 2014; 384, 9948: P1075-1076 from the Lancet series on Midwifery, Available from https://www.thelancet.com/series/midwifery [Accessed 05/04/2023].

- International Confederation of Midwives, Bill of rights for women and midwives Available from: internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/general-files/2019/01/cd2011_002-v2017-eng-bill_of_rights-2.pdf [Accessed 05/04/2023]