The COVID-19 pandemic has been described as a very difficult and trying time by those who work in the Care Home environment. On reflection, for me as a nurse leader, it has been one of the most challenging experiences of my career. However, I’d like you to now consider how it must have felt for a person living in a care home, perhaps being in your last years of life, and being advised you must spend your time, in your room, alone.

The Campaign to end loneliness project state that ‘Covid-19 had a clear and immediate impact on everyone’s ability to connect socially with others.’ Jones and Jopling (2021) adds that if you were already lonely before the pandemic, you were likely to become even more lonely.

The residents I’ve spoken to as part of a quality improvement project (QIP) looking at the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on levels of social isolation and loneliness experienced by people living in care homes, described feelings of hopelessness, heartache, feeling ‘empty’ and like their lives were ‘on hold’ when Covid-19 restrictions were placed on care homes during the pandemic.

Why do we need to tackle loneliness?

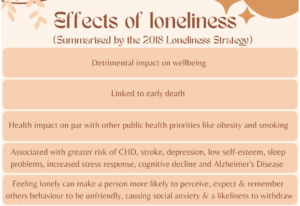

Loneliness is a feeling that most people will experience at some point in their lifetime. Prolonged exposure to loneliness can have a detrimental impact on a person’s wellbeing. The Department for Digital, Cultural, Media and Sport (2018)’s loneliness strategy update details the researched effects of loneliness below:

How do you assess whether someone is lonely?

Guidance written by the Campaign to End Loneliness (2015) encourages providers to assess the levels of loneliness as it helps to ‘demonstrate the positive impact of your work on the way people feel about their relationships and connections – and gives you a more detailed understanding than a wellbeing measure can.’

After establishing consent to take part in the project, I began by assessing residents’ levels of loneliness, shortly after a period of COVID-19 restrictions within the care home. In line with the government and UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) guidance at the time, this included restrictions on families, friends and volunteers visiting, no group gatherings between residents (i.e., residents isolated to their rooms), and no external visits from the community including entertainment, or schools.

The assessment tools used were a combination of an extended version of the gold standard UCLA 3-item loneliness scale (Figure. 1) and direct questioning. Campaign to end loneliness advises that using the UCLA scale alongside the single direct question ensures ‘loneliness is being measured using a scale that has been assessed as valid and reliable and the single item allows the respondent to say for themselves whether they feel lonely which provides insight into the subjective feeling of loneliness.’

As loneliness is linked to low mood and depression, I also wanted to determine whether the residents were experiencing this, and therefore used two reliable and validated tools to assess for loneliness and depression the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

What were the initial findings?

As I had spent time with these residents, I was able to witness the impact of the restrictions first-hand. Now I had the evidence to confirm what I could see.

All residents assessed had a score over 30 out of a maximum of 80, indicating that they were experiencing severe loneliness – one resident had a score of 61. This gentleman had also been assessed as experiencing moderate to severe depression in the PH-9 questionnaire.

Out of the ten residents who started the project, I focused on the five residents scoring highest on the loneliness assessment. One of these residents was not able to continue with the project, so the planned interventions, and reassessment of loneliness was completed for four residents in total.

What were the wellbeing interventions?

I looked at different wellbeing interventions for these four residents to improve the level of relationship centred care that we were able to offer within the COVID-19 guidance still affecting care homes. This included:

- Increase in opportunities to spend time with family and friends.

- Increase in volunteer provision.

- Using a patient-led model to develop individual and group activity planning and provision.

- Increase reach to community groups and develop relationships and interaction opportunities for residents.

- Develop the care home team’s understanding, focus and capacity to provide meaningful one-to-one activity.

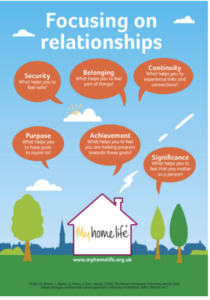

The aim of such interventions is to help the person feel a greater sense of security, purpose, value, belonging, continuity, achievement, and significance – which in turn should lead to an improvement in experiences of feeling socially isolated and lonely. This idea (Figure. 4 or click here) is one of the guiding principles of relationship centred care promoted by My Home Life. My Home Life are a charity working to promote positive practice and improve quality of life for people living in care settings, by using evidence-based frameworks and collaborative working.

For the gentleman described earlier with the highest score on the loneliness assessment, we were able to find a volunteer with similar interests to meet with him regularly as well as an increase in the one-to-one time spent with a carer (in line with our ‘Keyworker’ programme) to increase connections. Our Wellbeing Coordinator spent a great deal of time speaking with the resident to understand more about his values, interests, and hobbies to create a tailored wellbeing plan – including finding ways he might like to contribute towards the events planned in the home, and in the community. As the restrictions within the home at the time had lessened, he was also able to spend more meaningful time with his family.

What difference did it make?

Although there were some challenges to putting these interventions in place (including some physical health deterioration for residents, reduction in volunteer provision following COVID-19 pandemic, and some ongoing barriers relating to some restrictions) we were able to put most of them in place for the four residents who started the project.

After wellbeing interventions had been in place for six months, I asked the four residents to complete the assessment again. The residents on average were experiencing a reduction of 26% in their loneliness and social isolation score.

For the gentleman discussed above, on reassessment he scored 43, a reduction of 30% – and an associated 56% reduction in his score for low mood and depression, meaning he was now experiencing mild depression in contrast to his earlier of assessment of experiencing moderate to severe depression. He began leading poetry and discussion groups, decided to come out of his room more frequently for social events, and appeared more engaged and less anxious around his health concerns.

Looking at the wider picture, across the UK there is growing research that ‘social prescribing’ has a positive impact on a person’s wellbeing, including their physical and mental health, and that this can lead to a reduced need to access primary and acute care settings. Social prescribing is part of the NHS Long Term Plan’s (2019) commitment to personalised care and can ‘empower people to have a greater say in their lives and health’ (Public Health England, 2022). Can this idea be used more widely within social care to enhance the experiences of people living in care homes, and reduce the need to access acute health care settings?

Can this practice and interventions be sustained?

Since re-assessing the resident’s loneliness and isolation scores, the care home has seen further periods of outbreak measures and in line with the government guidance, periods of restrictions.

Current government guidance on Covid-19 outbreak measures in care homes, found here gives advice on how outbreaks in care homes should be managed. It discusses ‘proportionate changes to visiting’ and a ‘proportionate reduction in communal activity.’ This means a reduction in the opportunity for meaningful connections for all residents living in a care home experiencing outbreak measures.

There is clear evidence that the older person remains at high risk of becoming severely unwell if they are infected with COVID-19. However, I would argue that if a person has little to no access to something that gives them meaning to their life, this can also lead to a person becoming severely unwell.

All residents in our home have chosen to receive the COVID-19 booster vaccinations but are not given the option to make an informed decision on whether they would like to stay in their rooms with limited communal activity, and certainly no access to community entertainment or groups, if someone else within the home tests positive to COVID-19.

Care home staff and visitors are no longer required to wear face masks outside of outbreak measures (along with some other considerations) which has been mostly welcomed due to being a way of reducing one of the barriers to effective communication with the older person. Naturally, this will mean an increased chance of recurrent COVID-19 outbreaks due to the prevalence of the virus within the community. Does this mean that care homes will continue to be in and out of outbreak measures indefinitely? Is there a case for reducing the amount of testing, with a shift in focus to symptom management, as we do with other respiratory illnesses? I am a strong believer and advocate for reminding the decision makers within the government and the UK Health Security Agency that care homes are where people live, they are homes, not hospitals.

How can care homes continue to fund external providers for entertainment, and build community links if they are having to cancel them when they are in outbreak mode? How can wellbeing interventions and practices be sustained if care homes are continually in and out of COVID-19 outbreak measures? I would urge the decision makers to seek out the voices of people living in care homes to develop further guidance and consider what impact continued restrictions are having on levels of loneliness and social isolation experienced by people living in care homes.

References:

Campaign to end loneliness (2015) Measuring your impact on loneliness in later life. London. Available at: https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Loneliness-Measurement-Guidance1.pdf

Jones, D. and Jopling, K. (2021) Lessons from Lockdown: Loneliness in the time of COVID-19. Campaign to end loneliness. London. Available at: https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Lessons-from-lockdown-FEB21.pdf

Department for Digital, Cultural, Media and Sport (2018) ‘A connected society: A strategy for tackling loneliness – laying the foundations for change’. London. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/936725/6.4882_DCMS_Loneliness_Strategy_web_Update_V2.pdf

Websites:

Campaign to end loneliness: Covid-19 https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/covid-19/

Campaign to end loneliness; Evaluation https://dev.campaigntoendloneliness.org/evaluation/

My Home Life – Guiding principles: Focusing on relationships https://myhomelife.org.uk/our-guiding-principles/focussing-on-relationships/#main

My Home Life https://myhomelife.org.uk/

Public Health England (2022) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-prescribing-applying-all-our-health/social-prescribing-applying-all-our-health#:~:text=Social%20prescribing%20improves%20outcomes%20for,facet%20of%20community%2Dcentred%20practice.

UK Government publications: Infection prevention and control in adult social care – Covid-19 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/infection-prevention-and-control-in-adult-social-care-covid-19-supplement/covid-19-supplement-to-the-infection-prevention-and-control-resource-for-adult-social-care