Blog by Arthur Rose and Luna Dolezal

Criticisms of the Chinese response to the coronavirus pandemic have frequently used “saving face” to explain China’s politicized public health strategy. “Saving face” has also been used to explain Japan’s delayed decision to cancel the 2020 Olympics and Pakistan’s return to work on the Belt and Road project. In the expression, “face” connotes an honorable position that commands respect. To protect, establish or maintain this position is to save face. To lose face indicates a public loss of reputation or respect, often accompanied with public shame or embarrassment. During the Covid-19 crisis, “saving face”, and its corollary “losing face”, have emerged as affective drivers that explain the policy decisions of some nation states and organizations.

On 2 April 2020, the UK Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, outlined a “five-pillar testing plan”, with the goal of achieving 100,000 tests a day by the end of April. The goal, already a revision on an earlier target of 250,000 tests a day set by the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, became a central feature of the government’s daily briefings. The number of daily tests was enumerated alongside figures of the infected and the deceased. It became a point of fixation, detracting from both the deaths and the government’s continuing failure to source adequate amounts of PPE. On 1 May, Hancock announced, with audible emotion, that the “audacious” target had been reached with 122,347 tests carried out on 30 April. The figure was immediately set upon by journalists, as John Newton, Director of Health Improvement for Public Health England, acknowledged that it included more than 39,000 testing kits that had only been mailed on the 30th. This led to an urgent debate over whether the government had achieved this goal only by redefining the protocol for counting tests. The Health Service Journal reported that efforts to achieve the goal were “manic” and that Matt Hancock was “obsessed” with reaching the target. What had been “a stretching, ambitious goal” aimed at having “a galvanising effect”, threatened to be a personal and political blow for Hancock and a national embarrassment for Johnson’s government.

The goal of testing 100,000 people is difficult to reconcile with the UK government’s mantra that they are “following the science” when determining public health measures. Experts suggested there was no clear reasoning for that particular number of tests. Nor does the number make much sense without other measures, such as reliable contact tracing and isolation. However, repeatedly invoking the idea that politicians are fastidiously “following the science”, lends a rational and impartial view to the measures that are being taken. As Jana Bacevic has argued, there is no singular ‘science’: scientific theories and hypotheses are necessarily based on interpretation, often ideologically loaded and epistemically biased. The ‘science’ is regularly contested. In the case of Covid-19, the ‘science’ is patchy: data is sparse and disease modelling is standing in for hard and fast facts. Moreover, political emphasis on the 100,000 tests a day target, and the relative downplaying of the PPE shortages and comparatively high death tolls, suggest ‘following the science’ is hardly the whole story. It seems reasonable to be worried that concerns with political reputation management and ‘saving face’ are overriding a more scientifically-grounded public health strategy.

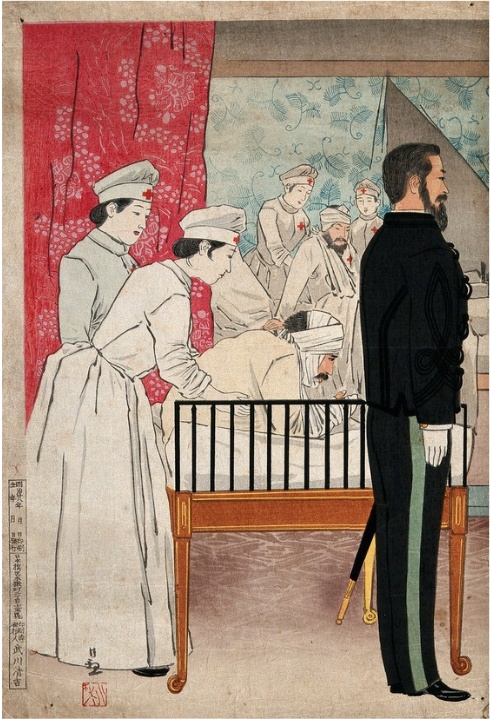

The persistent orientalising of the idea of “saving face” derives in part from an culturally essentialist view on shame popularised by the cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict in her 1946 book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, which differentiated cultures according to the prevalent use of either shame or guilt in ensuring social order and conformity. Whereas Western Europe and America relied on a sense of guilt, or one’s ‘conscience’, as an internal sanction, the use of shame, Benedict argued, was characteristic of Eastern cultures where a baser fear of reputation damage kept people in line. Benedict’s dichotomy has long been disputed, but it periodically reemerges as a racist trope in support of cultural essentialism. Western face saving seems altogether present in the fear of reputation damage that pervades the rhetoric of the UK’s daily briefings, from the repeated avowals of confidence in the UK’s “world-leading scientists” and the NHS’s continued resilience to the insistence that the UK won’t be “the worst hit country in Europe”. Perhaps such face saving rhetoric is useful when it comes to mobilizing a country and boosting public morale. We question its efficacy, however, when it dictates political interventions in public health policy.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [217879/Z/19/Z].

Arthur Rose is a Vice Chancellor Fellow at the University of Bristol. He is currently completing a book titled Asbestos: The Last Modernist Object. Twitter: @eclecticpneumas

Luna Dolezal is a Senior Lecturer in Philosophy and Medical Humanities at the University of Exeter. She is the PI on the “Shame and Medicine” project funded by the Wellcome Trust. Twitter: @lunadolezal