By Millie Davies

Access and engagement with healthcare among vulnerable groups is a particular interest of mine. Supervised by Professor Helen Ward from Imperial College London School of Public Health, and veteran in the field of sex workers services, I focused my Global Health BSc project on the identification of current sex worker services in London, and assessed how the number of these services and their comprehensiveness have changed over time.

A report by the House of Commons in 2016 identified that there were around 60,000 to 80,000 sex workers in the UK (1). Although statistics on sex work are difficult to assess due to the transience and marginalisation of this community, these statistics highlight that there is a significant number of workers in the UK sex industry.

Sex workers face a multitude of barriers to healthcare, of which stigma and discrimination play a large role, affecting both health and wellbeing (2). During the 1980s, a wide range of services specifically for sex workers were developed around the UK to increase their access to healthcare. Initially these services focused on control of STIs and HIV, but progressively developed to combat other issues faced by this community in terms of health and social care. Comprehensive services provide holistic care for sex workers addressing their sexual, mental and general health as well as providing drug and alcohol services, counselling and outreach services, where resources are taken out onto the streets as well as into a variety of indoor locations.

A study from the Praed Street Project in the 90s suggested that a third of sex workers were not registered with a general practitioner (3). This suggested that many sex workers only accessed health and social care services through sex worker-specific services, rather than through GPs. Today, sex workers continue to face barriers to care and specialised services are known to be crucial for protecting health and wellbeing as well as increasing positive health outcomes (4). Sex workers in touch with services have been shown to be more likely to have had an STI check within the past 6 months, suggesting increased health status and health awareness (5). Directories from 1995 and 2007 showed that a large number of specialist services for Sex Workers in the UK existed (6,7), however, since 2007, there has been no update of information on services, nor any assessment of how these services had changed over time.

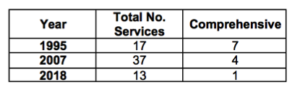

From my audit of current sex worker services in London, I identified 13 dedicated services for sex workers in London. This is a reduction from 17 and 37 in 1995 and 2007 respectively. This seems to suggest that there was a great surge of services set up through the noughties, but then a steep decline in more recent years. However, it is incredibly difficult to assess whether there was a true millennial spike in services or merely increased fragmentation or amalgamation of current services.

To assess the comprehensiveness of services past and present, I adapted the Sex Worker Implementation Tool from the World Health Organisation (8). Using this tool I was able to create four criteria for a comprehensive service:

- safe space (drop-in)

- clinical services

- drug services (needles exchange and/or drug treatment)

- mental health support (counselling).

I identified that 7 services in 1995, 4 in 2007 and only 1 in 2018 provided sufficient services to be considered ‘comprehensive’. There has been a constant decrease in the number of services deemed comprehensive since 1995, despite the peak in services available in 2007. Unfortunately, I was not able to include outreach in this assessment, due to the lack of information about outreach services in the 1995 directory. This is important to note because outreach is key to reducing STI rates among sex workers as well as aiding health promotion (9), and so should be included in any comprehensive service.

As well as the audit, I collected the personal opinions of five key informants, including service providers and ex service providers. These five informants had over 80 years of experience between them working in services for sex workers. They expressed their thoughts and opinions about how and why services for sex workers had changed over the past 20 years. Many topics and explanations for the reduction in services were given, but all informants identified lack of funding as the major concern and cause for these changes.

Funding cuts have been made across most sex worker specific services with Grenfell et al. (2016) finding budget cuts of over 40% were planned for Open Doors services (9), which is the main resource for sex workers in East London. Cuts of this magnitude will have detrimental effects on the provision of care by reducing the capacity for outreach work and the limitation of in-house services. Changes to how funding is acquired through commissioning from local authorities was also emphasised by my informants as a key cause of change and increasing fragmentation of services. Three of the informants expressed disappointment at the separation of clinical and health promotion services by commissioning groups, suggesting that this was a major reason for the reduction in comprehensive services.

I also found that due to re-commissioning, services in London are volatile due to frequent change in service providers. This made the identification of open and available services challenging, which also highlights the potential difficulty sex workers themselves may face in easily and quickly identifying available services. Providing services to vulnerable groups such as sex workers requires the development of a trusting relationship with continuity and familiarity in care. Trust between sex workers and service providers was highlighted by all key informants as vital to providing effective and efficient care. Renewal of commissioning on a three-year contract opens up to change and discontinuity of services, making a trusting relationship difficult. This further isolates sex workers from services and challenging outreach capability. One informant talked of closure of sex worker ´flats´ to service providers, stemming from this loss of trust. The effect is decreased engagement with services causing health and wellbeing to suffer.

All informants also identified policing as having affected the trust of services by sex workers, due to increases in prosecutions and enforced movement of sex workers out of London areas, such as Soho. While the debate around decriminalisation continues, National Ugly Mugs argues that greater policing of sex work only further isolates sex workers and makes them more vulnerable to violence (10). This change in policing has been well-documented in both scholarship and the media (11-13), however there is little information on the opinions of sex workers themselves.

This audit identified that since 1995 there has been a reduction in the number of comprehensive services for sex workers in London. I found that Changes in funding and policing are thought to have had significant effects on service provision, however this only scratches the surface as to the issues both service providers and sex workers face. Further work is needed to assess how these changes are affecting the health and wellbeing of sex workers, as well as what can be done in the future to protect this potentially vulnerable group.

Twitter @milliead95

References:

(1) Commons H of. Prostitution: Third Report of Session 2016-17. 2016.

(2) Benoit C, Jansson SM, Smith M, Flagg J. Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers. J Sex Res [Internet]. 2017;0(0):1–15. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652

(3) Ward H, Day S, Scambler G. Health care and regulation: new perspectives. In: Scambler G, editor. Rethinking prostitution: Purchasing Sex in the 1990s. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 1997. p. 139–64.

(4) Jeal N, MacLeod J, Salisbury C, Turner K. Identifying possible reasons why female street sex workers have poor drug treatment outcomes: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):1–9.

(5) Cusick L, Mart A, May T. Vulnerability and involvement in drug use and sex work. London; 2003.

(6) Ziersch A, Casey M, Ward H, Day S. Handbook of sexual health services 1995. London; 1995.

(7) UK Network Of Sex Work Projects. Directory of Services – Services for Sex Workers. Manchester; 2007.

(8) Global Network of Sex Work Projects. The Smart Sex Worker’s Guide to SWIT [Internet]. Edinburgh; Available from: https://apnswnew.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/smart-guide-to swit_pdf_0.pdf

(9) Grenfell P, Eastham J, Perry G, Platt L. Decriminalising sex work in the UK. BMJ [Internet]. 2016;354(August):i4459

(10) National Ugly Mugs [Internet]. [cited 2018 May 20]. Available from: https://uknswp.org/um/

(11) Bowcott O. Police accused of threatening sex workers rather than pursuing brothel thieves. The Guardian [Internet]. 2017 Aug 3; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/aug/03/police-sex-workers-brothel-thieves-london-keir-starmer

(12) Hartley A, Foster R, Brook M, Cassell J, Mercer C, Coyne K, et al. Assessment of the impact of the London Olympics 2012 on selected non-genitourinary medicine clinic sexual health services. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(5):329–35.

(13) Nunn A. 100 arrested for prostitution related offences in Ilford Lane, Ilford. Ilford Recorder [Internet]. 2013 Sep 6; Available from: www.ilfordrecorder.co.uk/news/crime-court/100-arrested-for-prostitution-related-offences-in-ilford-lane-ilford-1-2369256