Understanding screening is difficult. Responses to screen, or not to screen individuals, is often an emotional topic. This blog sets out evidence that might inform such screening decisions.

If I get something wrong, or there is something you’d like to discuss then email me, send a message via twitter – I’ll add or correct the post and respond. (Updated 18th Feb)

Why Lung Cancer?

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death accounting for about 3 out of 10 of all cancer deaths worldwide. It is also a neglected disease. A Focus on lung cancer is much needed and essential to improving outcomes that are currently very bad: UK one-year survival is 32%, at 5 years it is 9.5%.

Screening – does it make a difference?

One way to try and improve outcomes is screening, but does it make a difference?

On the 7th of Feb, Greg Fell, Margaret McCartney and myself set out our concerns about the rollout of the lung cancer screening programme in the NHS. We were concerned about the commissioning arrangements for cancer screening and whether they ensure patient safety, cost-effectiveness and could deliver real mortality benefits for patients.

You can read the Lung cancer Letter here.

On the 8th of Feb, the NHS ‘rolled out’ lung cancer screening trucks across the country. The press release stated:

- A recent study showed CT screening reduced lung cancer mortality by 26% in Men and between 39% and 61% in women*.

- The Manchester project scanned 2,541 patients and found 65 lung cancers affecting 61 patients.

- Prior to the study 18% of lung cancers were diagnosed at stage one and 48% stage four. After the study, 68% of lung cancers were diagnosed at stage one and 11% were stage four.

That evening Deb Cohen, BBC Newsnight, reported on the rollout of NHS Lung Cancer screening — BBC Newsnight (@BBCNewsnight) February 8, 2019

“We’ve got huge variation in care in the UK… we need better diagnostics, better provision of treatment, you need multi-disciplinary teams and that infrastructure in place to deliver this” – Professor Carl Heneghan tells #newsnight

You can see the interview with me here

The UK National Screening Committee (UKNSC) is the screening equivalent of NICE. It does not currently recommend lung cancer screening. The premise of screening is if you catch it earlier then you improve outcomes. Job done. This is based on the different survival rates at different stages of the disease.

- Stage 1 Around 35 out of 100 people (around 35%) will survive their cancer for 5 years or more after diagnosis.

- Stage 4 There are no statistics for stage 4 cancer because sadly many people don’t live for more than 2 years after diagnosis.

However, our understanding of the progression of cancer is changing: not all stage 1 disease progresses quickly, some doesn’t progress at all and some regresses. This problem is referred to as overdiagnosis. ‘by identifying problems that were never going to cause harm or by medicalising ordinary life experiences through expanded definitions of diseases.’ See Overdiagnosis: what it is and what it isn’t for a more in-depth discussion on this topic.

Effects of screening in trials

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) is the largest trial (and only to report in full to date) that reported reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose CT screening. Published in the NEJM in 2011 the NLST compared three annual CT scans with x-ray and found that absolute mortality was reduced. There were 247 deaths from lung cancer per 100,000 person-years in the low-dose CT group and 309 deaths per 100,000 person-years in the radiography group.

Margaret McCartney in her BMJ news and review column expresses the absolute results for all-cause mortality: ‘Absolute mortality 7.02% v 7.48% at a median follow-up of 6.5 years’). The number needed to screen to prevent one death from lung cancer was 320.’

To put this result in perspective, the reported reduction in deaths from lung cancer with CT screening is larger than the reduction seen with mammography for breast cancer.

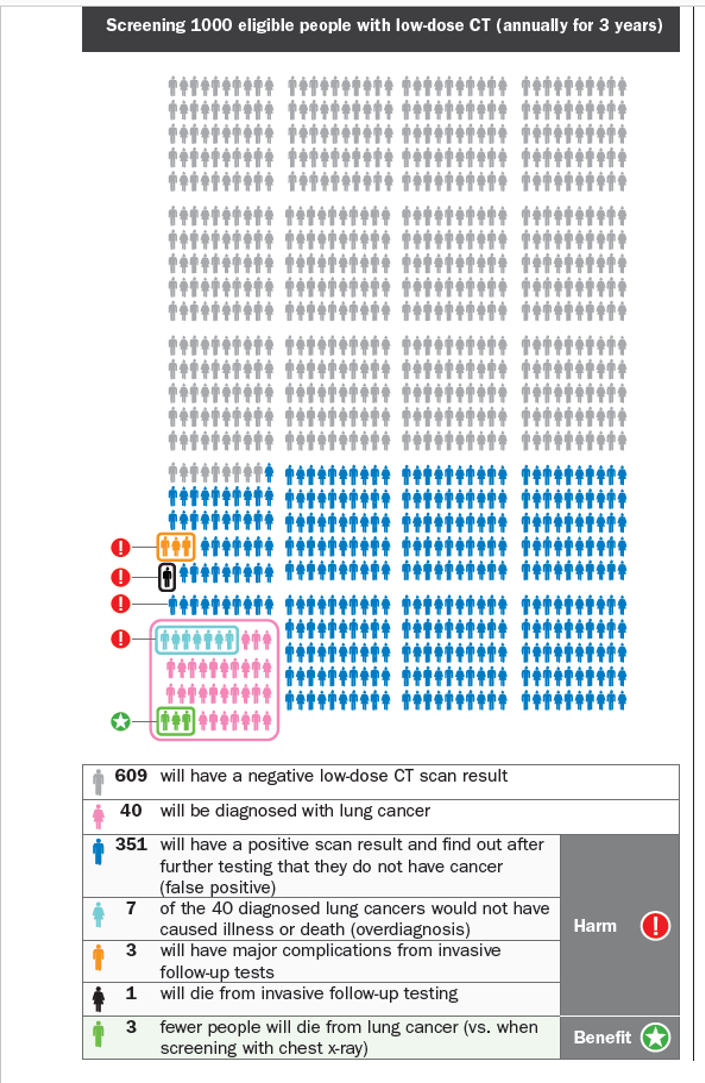

The Canadian Task Force guidelines used these data to provide clear recommendations with helpful information leaflet that explains the risk and benefits. These were the results used by Newsnight – 365 patients in 1000 had at least one false alarm.

The Canadian Task Force guidelines used these data to provide clear recommendations with helpful information leaflet that explains the risk and benefits. These were the results used by Newsnight – 365 patients in 1000 had at least one false alarm.

Recommendations from the Canadian Task Force include:

For adults aged 55-74 years with at least a 30 pack-year* smoking history who currently smoke or quit less than 15 years ago, we recommend annual screening with LDCT up to three consecutive times. Screening should ONLY be carried out in health care settings with expertise in early diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Weak recommendation

A weak recommendation means that most eligible people would want to be screened for lung cancer, but many may appropriately choose not to be screened

They also state that the accuracy of detection and quality of follow-up investigations and management are critical to obtaining more benefit than harm, screening for lung cancer with LDCT should only be considered in settings that can deliver comprehensive care similar to or better than that offered in the NLST trial.

- NLST radiologists and radiologic technologists were certified by appropriate agencies or boards

- Results and recommendations from the interpreting radiologist were reported in writing to the participant and his or her health care provider within 4 weeks after the examination.

- The NLST was conducted at a variety of medical institutions, many of which are recognized for their expertise in radiology and in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

- one of the most important factors determining the success of screening will be the mortality associated with surgical resection, which was much lower in the NLST than has been reported previously in the general U.S. population (1% vs. 4%)

This then throws up a whole host of questions that UK screening trials could, and should, try to answer: will populations with risk profiles different from the NLST participants benefit? Are less frequent screening regimens equally effective? How long should screening continue for? Would different criteria for a positive screening result, such as a larger nodule, still give the same mortality benefits? Does worse quality care lead to more harm and more deaths?

Greg Fell, Public Health Doc in Sheffield, wrote an excellent summary here: as he says, he knows a thing or two about screening.

Further evidence is provided by the NELSON lung cancer screening trial:

Findings from the NELSON trial were presented at the IASLC 19th World Conference on Lung Cancer. See the press release here

This is the second large trial and is still ongoing. Participants in the trial were randomized to CT screening at baseline, 1, 3, and 5.5 years or to usual care. The uptake of screening was 95% at year 1, which decreased to about two-thirds after 6.5 years of follow-up.

The abstract reports that at year 10, there were 214 lung cancer deaths in the male control arm and 157 deaths in the screened arm. The lung cancer mortality rate ratio for men in the screened vs unscreened arm was 0.74 (26% reduction, P = .0003).

The results report overall, CT scanning decreased mortality by 26% in high-risk men and up to 61% in high-risk women over a 10-year period.

I could not calculate absolute effects, and I’m fairly confident that the results presented are only for lung cancer-specific mortality, not all-cause mortality. This is important. Reductions in disease-specific mortality may not translate into reductions in all-cause mortality, In some cases, you may increase mortality. And, as in the NLST example, the effect is larger for the disease-specific effect compared to the all-cause mortality effect.

An issue that gives rise to misleading results. Take a look at Competing risks and cancer-specific mortality: why it matters if you want to understand more:

“We found that both the 5-year lung cancer-specific and noncancer-specific cumulative incidence of death increase with age. We also reported a higher incidence of noncancer-specific mortality compared with lung cancer-specific mortality among patients who were ≥75 years of age that lasted up to 2 years postresection. These findings highlight the necessity of accounting for noncancer-specific mortality as a competing event when assessing cancer-specific mortality in elderly patients.”

I’ve also been alerted to this excellent article in the BMJ by, Gerd Gigerenzer, on how five-year survival rates can mislead. ‘Why is an increase in survival from 44% to 82%, not evidence that screening saves lives?’ Two reasons: lead time bias and overdiagnosis.

In 2017, the effect of a 2.5-year screening interval in the Nelson trial was reported. Compared with the first three screening rounds a higher proportion of advanced disease stage lung cancers were detected. Participants in the fourth round were more often current smokers. Stopping smoking is essential to improving outcomes. Lung cancer screening should, therefore, be coupled with effective smoking cessation interventions.

Yet, smoking cessation services are being cut in the latest public health rationing moves. Disjointed preventive services ensue if the whole system of care isn’t joined up.

Impact of rolling out screening

The Veterans Health Administration in the US implemented lung cancer screening in eight academic VHA hospitals where 93,033 primary care patients were assessed on screening criteria. Published in JAMA, they found that of the 4246 patients who met the criteria (58%) agreed to undergo screening and 50% (2,106) underwent the CT scan. Of these 2,106 (60%) had nodules, and 1,184 (56%) required tracking (857 patients (41%) had 1 or more incidental findings reported).

A total of 73 patients (3.5% of all patients screened) had suspicious findings and underwent further evaluation – 31 (1.5%) had lung cancer. They concluded that implementation may stress the capacity of radiology services, it will require additional training for a host of staff, will lead to large numbers of eligible patients and require substantial clinical effort for both patients and staff. They also stress there is a need to learn more about decision aids and optimal ways to use them in lung cancer screening.

Conclusion

In our letter, we state In our experience, few “understand” screening, and there is a significant misunderstanding about the differences between screening and case finding. Often, in our experience, people misconstrue screening, significantly underplay (or don’t understand) the harms and overplay the benefits.

For now, I’ll leave you to ponder on the evidence for screening and the levels of misunderstanding; this post is a work in progress: updated with your views and further thoughts on the evidence……I look forward to your comments.

Carl Heneghan,

Editor in Chief BMJ EBM,

Professor of EBM, University of Oxford

Further posts:

16 Mar 2018: Why I am confused about lung cancer screening | BMJ EBM Spotlight

Competing interests

Carl has received expenses and fees for his media work including BBC Inside Health. He holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, The NIHR Oxford BRC and the WHO. He has also received income from the publication of a series of toolkit books. CEBM jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with some international partners which are based on a non-profit model.

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine – original evidence-based research, insights and opinion

Read more in the Welcome to BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine Editorial.

References

- Public Health England. UK National Screening Committee recommendation on lung cancer screening in adult cigarette smokers. Jul 2006. https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/lungcancer.

- University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust. Lung cancer early diagnosis rates soar during UK-first CT community scanner pilot in Manchester by UHSM. 15 Mar 2017. https://www.uhsm.nhs.uk/news/lung-cancer-early-diagnosis-rates-soar-uk-first-ct-community-scaner-pilot-manchester-uhsm/.

- Macmillan Cancer Support. Macmillan lung health check pilot. Aug 2016. www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/lung-health-check-manchester-report_tcm9-309848.pdf.

- Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med2011;357:395-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 pmid:21714641.

- Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA, et al. Final screening round of the NELSON lung cancer screening trial: the effect of a 2.5-year screening interval. Thorax2017;357:48-56. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208655 pmid:27364640.

- Khomami N. Around 40% of local authorities cutting budgets for smoking cessation services. Guardian 13 Jan 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/13/local-authorities-budgets-stop-smoking-services.