A manifesto for Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) was published in the BMJ earlier this year and presented at Evidence Live.

Jeff Aronson has been thinking again about the word manifesto.

The Indo-European root MAN meant a hand. The Latin word was manus, from which we get words such as maintain, manacle, manage, manège, manicure, manipulate, manner, manoeuvre, mansuetude, manual, manufacture, [manu]factory, manumit, and manuscript. Manqué, an adjective that refers to an unfulfilled ambition (e.g. a scientist manqué), is from the Latin mancus, having a useless hand. To emancipate is to take someone by the hand (Latin capere, to take). An amanuensis (short for servus a manu plus the suffix -ensis, belonging to) writes things out by hand at another’s dictation, as Tolstoy’s wife, Sofya Andreevna, did for him and as Eric Fenby did for the composer Frederick Delius. The manubrium sterni is like a handle, comparing the body of the sternum (Greek στέρνον the chest) to the blade of a sword, and the xiphoid process (ξίϕος a sword) to its tip.

The Indo-European root MAN meant a hand. The Latin word was manus, from which we get words such as maintain, manacle, manage, manège, manicure, manipulate, manner, manoeuvre, mansuetude, manual, manufacture, [manu]factory, manumit, and manuscript. Manqué, an adjective that refers to an unfulfilled ambition (e.g. a scientist manqué), is from the Latin mancus, having a useless hand. To emancipate is to take someone by the hand (Latin capere, to take). An amanuensis (short for servus a manu plus the suffix -ensis, belonging to) writes things out by hand at another’s dictation, as Tolstoy’s wife, Sofya Andreevna, did for him and as Eric Fenby did for the composer Frederick Delius. The manubrium sterni is like a handle, comparing the body of the sternum (Greek στέρνον the chest) to the blade of a sword, and the xiphoid process (ξίϕος a sword) to its tip.

Add Latin manus to [in]festus, hostile or troublesome, and you get manifestus, caught in the act, red-handed, and therefore obvious, manifest. As Dryden wrote in Absalom and Achitophel, “Now, manifest of Crimes, contriv’d long since, He stood a bold Defiance with his Prince”. A manifest thus became a piece of evidence, such as the list of a ship’s cargo or any inventory, and a manifesto, from the Italian form of the word, then became evidence of intention: “a printed declaration, explanation, or justification of policy issued by a head of state, government, or political party or candidate.”

The earliest reference in English to a manifesto of this sort is to be found in Nathaniel Brent’s translation of Paolo Sarpi’s History of the Council of Trent (1620). Theodore Alois Buckley’s history of 1852 makes it clear that manifestos were commonly compiled at the time of the Council, which was an ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church held between 1545 and 1563. When, for example, the Emperor Charles V declared war on the Protestants in 1546, the elector of Saxony and the Landgrave of Hesse published a manifesto, declaring that “the war was really undertaken in the cause of religion”. This laid at least some of the blame on the Council and the then Pope, Paul III (Alexander Farnese), with whom the Emperor had a treaty, although the Emperor had declared it to be a secular campaign, not wanting his wishes to be associated with those of the Pope.

A manifesto is also “a book or other work by a private individual supporting a cause”, like Atul Gawande’s Checklist Manifesto (2009) and my 2010 manifesto for UK clinical pharmacology. The 1848 political pamphlet Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (The Communist Manifesto), by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, is perhaps the most famous example. Tsar Nicholas II issued the October Manifesto in 1905, promising political reforms and aborting the first Russian Revolution. Artists are fond of publishing manifestos describing their creeds; well-known examples include the Russian Futurists’ Manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1912), and the Surrealists’ Manifestos (1924) by André Breton. There are many other examples of varying seriousness.

Searching PubMed for the term “manifesto” in the titles of papers, I found nearly 250. The earliest all dealt with alcohol. The first, published anonymously in the British Medical Journal in 1902, was titled “A medical temperance manifesto” and reported that the Council of the British Medical Temperance Association in conjunction with the American Medical Temperance Association and the Association of German-speaking Medical Men, had agreed to issue an international manifesto on abstinence from alcoholic beverages. Their manifesto was again advertised in the journal in 1903 and later that year in the California State Medical Journal. The database lists no further manifestos until 1935, when the subject was again alcohol, again in the British Medical Journal, “The Brewers’ Attack upon Youth”, advertised in an article titled “The Beer Drinking Habit: Doctors’ Manifesto”; signed by “a thousand medical men”. This manifesto inveighed against a campaign by the Brewers’ Society “to get the Beer Drinking Habit instilled into Thousands, almost Millions, of Young Men who do not at present Know the Taste of Beer” (punctuation in the original). The 2012 legislation in Scotland on minimum unit pricing, delayed because of challenges from the Scottish Whisky Association, but now to be implemented from May 2018, could be considered the latest in this series of manifestos.This puts pressure on the rest of the UK to do likewise. The Welsh Parliament is already considering legislation.

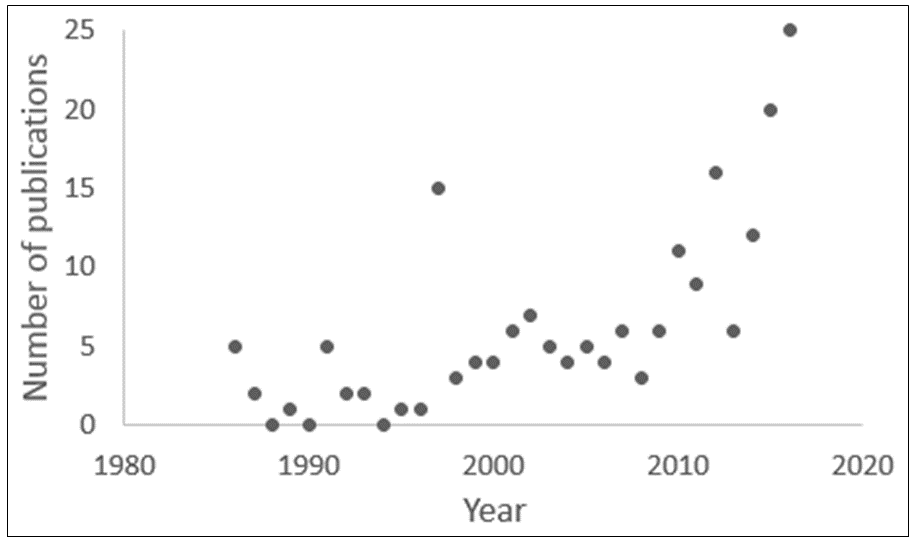

Since 1935, papers about manifestos have appeared sporadically. PubMed lists only 25 in the 84 years from 1902 to 1985. Since then the numbers have been variable (Figure 1), with a marked increase since 2010, although the numbers are still small. The main topics include public health, women’s health, the UK’s National Health Service, and various aspects of research and policy, including evidence-based medicine.

Figure 1. The numbers of papers containing the word “manifesto” in titles since 1986 (source PubMed); the 15 papers published in 1997 included a series of 12 titled “Osteopathic manifesto.”

The purpose of the EBM manifesto is to develop, disseminate, and implement better evidence for better healthcare in response to systematic bias, wastage, error, and fraud in research underpinning patient care. Its nine principles are to:

- expand the roles of patients, health professionals, and policymakers in research;

- increase the systematic use of existing evidence;

- make research evidence relevant, replicable, and accessible to end users;

- reduce questionable research practices, bias, and conflicts of interests;

- ensure that drug and device regulation is robust, transparent, and independent;

- produce better usable clinical guidelines;

- support innovation, quality improvement, and safety through the better use of real-world data;

- educate professionals, policymakers, and the public in evidence-based healthcare, so that they can make informed choices;

- encourage the next generation of leaders in evidence-based medicine.

During elections candidates or their parties may issue manifestos in which they outline their plans, which, if they are elected, they have a mandate to carry out. If they do not do so, or if they do things the manifestos did not include, they can be accused of abusing their mandate. Few people, I suspect, read political manifestos, which often contain weasel words and vague, platitudinous promises. It would be good to see a political manifesto that contained evidence instead.

Jeffrey Aronson is Associate Editor BMJ EBM, consultant physician and clinical pharmacologist, and Fellow of CEBM

Conflict of Interest: none declared