The limits of quality improvement

Rob Bethune is a surgical registrar in the Severn Deanery. Follow him on twitter – @robbethune

If, like me, you believe in the power and importance of clinical teams running small scale quality improvement work, then you must find 15 minutes to watch this excellent and challenging presentation by Mary Dixon-Woods describing the evaluation of the Safer Clinical system project (the full written report is available here). If you have limited time then I would watch the video rather than reading my blog below; however, I will expand on some of her points and disagree slightly with part of what she says. The main message is that the impact of small groups of clinicians doing quality improvement (QI) work appears to be less than we might have hoped.

QI methodology does not solve all our problems

The key point that Mary Dixon-Woods makes is that quality improvement methodology (and here I mean the model for improvement, lean etc) cannot address all problems that healthcare faces, and I fully agree with this – although I would have disagreed if you’d asked me five years ago. The table below summaries this; if you cannot measure something often (at least monthly) in an effective and reasonable way, then improvement methodology falls down. Equally if you are looking at things that can only be addressed at institutional (ie national) level, then small groups of frontline clinicians and managers will not be able to influence this. For example, making epidural catheters incompatible with intravenous catheters or standardising the production of kits to place central lines.

Simple |

Complicated |

Complex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Adapted from Paul Batalden’s “textbook” of QI)

If you are trying to improve the care of rare conditions or presentations of diseases then QI methodology is not going to help you, and you need to target your interventions to improving culture (which of course is extremely hard). Whereas if you want it improve the quality and timeliness of discharge summaries, then QI methodology is perfect. Between these two relative extremes lies a grey area where small scale clinical teams doing QI are not going to achieve improvement alone, but the more comprehensive, well funded improvement work will. Mary Dixon-Woods gives the example of improving the timeliness of angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. This was a very well done quality improvement programme (although the cardiologists doing it might well not have called it that). They followed the model for improvement: a clear aim, continuous measurement (which has carried on beyond the timescale of the initial interventions), and multiple PDSA cycles. The big difference between this and most small scale QI work is funding. Primary angioplasty required a whole infrastructure to be built around if with a completely new set of staff; think of all those additional cardiac nurses and hundreds of interventional cardiologists. If sepsis (and in fact more specifically time to first antibiotic) had the same resources and used QI methodology then many more septic patients would get antibiotics sooner.

Small scale QI work as a tool for staff engagement

Working in systems that are inefficient and irritating has a negative impact on our ability to deliver safer care. For me one of the key aspects of doing small scale quality improvement work is that it can straighten out some of the irritations and genuinely engage staff in their working environment.[1] Even if their quality improvement work does not directly increase quality, its influence on staff morale ultimately will.[2] For this reason alone it is worth doing small scale quality improvement work. We must try and develop systems that then go on to make these changes sustainable and last beyond the enthusiasm of the clinicians and mangers involved, but this is proving to be difficult.

Finding the problems

The one area I would disagree with Professor Dixon-Woods is in identifying the quality problems. In the safer clinical system (SCS) programme a significant amount of time (five months) is spent analysing the current state of affairs to find out where the weaknesses lie, using techniques such as failure mode effect analysis (FMEA) and hierarchical task analysis (HTA). These methods were used in response to the inability of incident investigations in health care to find the real underlying causes of failure. On one hand these techniques do seem to find the real issues but I would strongly say that you don’t always need to do them. In the South West of England we have been running a programme for five years where we get first year doctors to run structured supported quality improvement work, where they chose the areas of work that they feel are the least safe and most inefficient. The list of projects they choose correlates extremely closely to the findings from the diagnostic phase of SCS. So you don’t need to spend five months (and a lot of money) doing HTA and FMEA, you just need to ask your frontline staff what doesn’t work and is unsafe – they have the answers! These methods do have their uses in healthcare but I do not think they need to be done routinely.

The road ahead

As a believer in quality improvement I found Mary Dixon-Woods video challenging, but this is no bad thing. It has helped me understand better the limits of small (and large) scale QI work and will hopefully allow me to be more refined in its application as the years go on and we continue with our never ending journey to improve the care we give our patients.

- Bethune R, Soo E, Woodhead P, Van Hamel C, Watson J. Engaging all doctors in continuous quality improvement: a structured, supported programme for first-year doctors across a training deanery in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22(8):613-7.

- West M. Employer Engagement and NHS Performance. Kings Fund 2012.

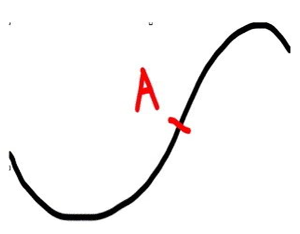

The simplicity chapter also describes Handy’s Curve. This is a well-known phenomenon in general management where any new initiative takes a short period to amass expertise or resources to get going and then has steady upwards growth. The sting in the tail is that by not planning the next steps or spread of the idea, death of the initiative is virtually guaranteed. The new ideas or changes need to be in place from the mid-point of the upwards curve – point A on the diagram. The NHS, as much of business, repeatedly fails to plan for the next steps early enough. Little wonder that staff get more and more sceptical about any shiny new initiatives delivering real sustainable change.

The simplicity chapter also describes Handy’s Curve. This is a well-known phenomenon in general management where any new initiative takes a short period to amass expertise or resources to get going and then has steady upwards growth. The sting in the tail is that by not planning the next steps or spread of the idea, death of the initiative is virtually guaranteed. The new ideas or changes need to be in place from the mid-point of the upwards curve – point A on the diagram. The NHS, as much of business, repeatedly fails to plan for the next steps early enough. Little wonder that staff get more and more sceptical about any shiny new initiatives delivering real sustainable change.