Improving clinical data quality: the digital health challenge

Dr Tim Yates is a registrar in neurology at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust. He is currently a National Medical Director’s Clinical Fellow at NHS Digital. @drtimyates

As far as digital health is concerned, it’s not all about infrastructure, apps, and electronic health records. It’s much more about making the healthcare data work for patients, clinicians, and the service. Data should be central to everything we do; it should be used and collected at the patient’s bedside as an essential part of good clinical care, and in its secondary uses in each quality improvement project we undertake and in determining payment for every service we provide. Accurate, precise, and timely data that are also high quality data provide the tools to make healthcare safer, more effective, and better value.

But we also learned from the Francis Inquiry that when data are false or misleading, poor or dangerous care can continue. That linkage between healthcare data quality and the clinical care it drives makes it imperative for clinicians to work in partnership with analysts to derive clinically meaningful measures of data quality.

Take something as fundamental as accurately recording a patient’s diagnoses which need to be coded and passed on. Through life, a patient may lose some diagnoses and receive new ones as they age and their health changes, meaning their set of diagnostic codes can change. But there is a range of diagnoses that patients typically never should lose, like rheumatoid arthritis or Alzheimer’s disease. Examining the persistence (or otherwise) of such fixed diagnoses over time offers a new way of assessing the quality of the record: a new method of healthcare data validation termed “diagnosis reporting consistency”.

On 8 November, NHS Digital published new data (broken down by Trust) for the consistency of reporting of dementia diagnoses with its latest quarterly Data Quality Maturity Index (DQMI) at http://content.digital.nhs.uk/dq. This looked at a range of ICD10 codes for dementia in the Admitted Patient Care (APC) national clinical data set.

The findings show how questions about data quality go hand in hand with clinical questions. Only 71% of patients with a diagnosis of dementia recorded for hospital admissions in the period April 2013 to March 2016 received this diagnosis recorded for admissions April to June 2016. A dementia diagnosis persisted for only 50% of admissions where patients were not admitted by their usual provider. Could improving the quality of the data improve the quality of the clinical care?

NHS Digital has a central role in collating, analysing, and publishing the DQMI, allowing Trusts to compare their data maturity. However, a combined effort to improve healthcare data quality must involve and take inspiration from all parties including individual administrators and clinicians today, and patients tomorrow. We have two quality challenges. First, to find ways to ensure that data entry is accurate at the bedside, not least making sure the diagnoses entered are accurate and comprehensive. Second, to inspire frontline clinicians to engage with the data quality agenda because it is the great enabler for the care they want to deliver.

Trusts recognising the value of this work have embedded data quality improvement strategies in their clinical culture. They benefit from more accurate patient data and this is reflected in higher DQMI scores. Where Trusts are looking to improve, NHS Digital can help. It highlights excellent performance in the DQMI and helps the system learn from that as part of its Performance Evidence Delivery Framework. NHS Digital also hosts both electronic and face-to-face forums, where those interested in data quality improvement can discuss and take forward everything from new clinically-focused data validation methods to reports on local project work. The journey to better data and more clinically relevant data quality measures starts here with you.

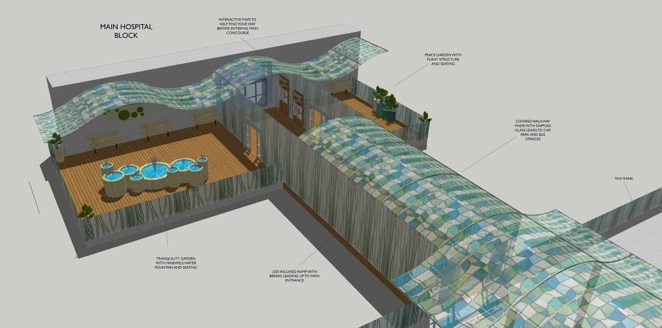

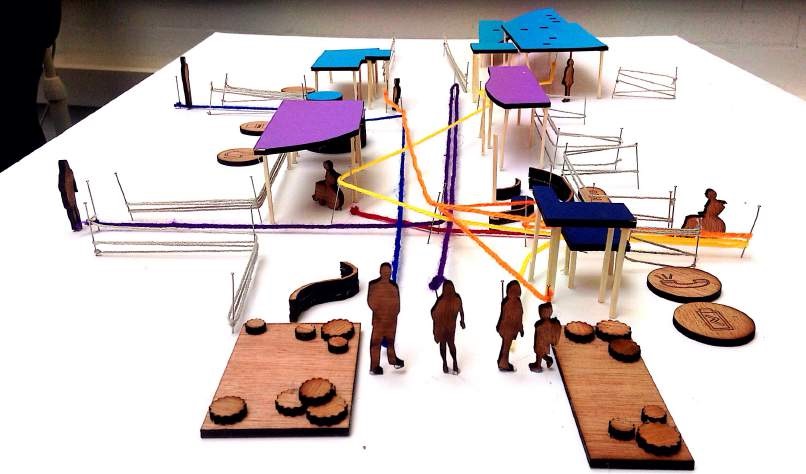

Morven Millar 3rd year Medical Student University of Dundee

Morven Millar 3rd year Medical Student University of Dundee

Biography

Biography what really matters to users, and employ the narratives to inform patient focused service

what really matters to users, and employ the narratives to inform patient focused service

Dr Howard Ryland is a Registrar in Forensic Psychiatry at South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust. He was previously National Medical Director’s Clinical Fellow at the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the Vice-Chair of the Academy’s Trainee Doctors’ Group. He is a member of the Academy’s Quality Improvement Task and Finish Group.

Dr Howard Ryland is a Registrar in Forensic Psychiatry at South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust. He was previously National Medical Director’s Clinical Fellow at the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the Vice-Chair of the Academy’s Trainee Doctors’ Group. He is a member of the Academy’s Quality Improvement Task and Finish Group.